How To Twist Shadows and Reflections

Some of the twists on the Original/Image relationship are not about breaks in Visual Correspondence

We have seen how the Original and Copy relationship can be a fertile source of imitation twists. So it is no surprise to find that the humorist can do the same with the Original and its Image, given that this second relationship, just like the first, features a marked degree of imitation to begin with. Images already imitate their originals with great flair, so the humorist can take this further by going beyond visual correspondence, to make the image behave like the casting object in other, non visual ways. This applies particularly to the shadows and reflections of human beings, where the casting object exhibits a great wealth of behavioural features that can be taken on by the image. But it is also the case that the casting object can take on the particular properties exhibited by its image, although in this case, the range of features is much smaller, as we shall see.

The ‘Image Behaves like its Original’

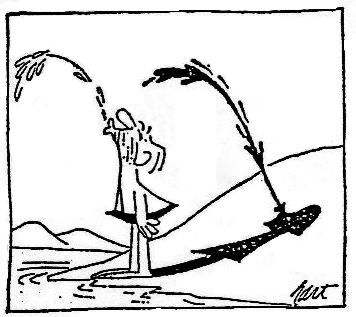

In some of the cartoons on visual correspondence already considered, we can find examples of twists on image imitation sitting happily alongside twists on VC. So now it is time to distinguish between these two types of twist. For example, we can look at the two cavemen cartoons below, where the shadows are shown spitting out water, in one case stoically, and in the other, impertinently. Because what we see in both these cases is that the shadows are not just breaking with VC, but that they are also taking on features of their casting objects, in an equally radical twist involving imitation. An imitation twist where the images are acting like honorary members of the human race, in what is clearly a case of ‘Image like Human’ anthropomorphism.

What we see in these two cartoons is that the value of the humour in each example seems to have less to do with the break in visual correspondence, and rather more to do with our seeing the shadows as actual living beings. Beings reacting just like we humans might react, given these particular circumstances. So we are clearly happy with the idea of these shadows as autonomous figures in their own right, exhibiting human behaviour, and existing as substantial beings, entirely at home in our own material world. And there can be no better candidate for such anthropomorphism, because the image of a human not only looks like us, but moves like us as well. Indeed, in the case of a reflection in the mirror, the likeness is so complete that it is more a case of us facing ourselves than it is an anthropomorphic extension of ourselves, out there in physical space.

The fact that many examples of the image imitation twist also fall into the VC category is hardly surprising. Because if the shadow is to behave like its human original, then some change in the shadow vis a vis its owner is almost inevitable. Especially when we realise that autonomy is one of the main human characteristics that the image is likely to imitate, and that means that the image has to break free of its casting owner. However, a break in VC is not absolutely inevitable, and in the cartoon story of the rich man and his two shadows that we consider in the next section, we see that the thoughts of the shadows do not in any way compromise the VC between the shadows and their original. This is because their speech is drawn up in separate speech balloons, whilst the shadow silhouettes remain absolutely faithful to their casting original, the wealthy man. (In fact, far from there being a break in visual correspondence, we find that the shadows are complaining about too much VC, precisely because that it is this sustained visual correspondence that is throwing them up against walls, and dragging them along the ground).

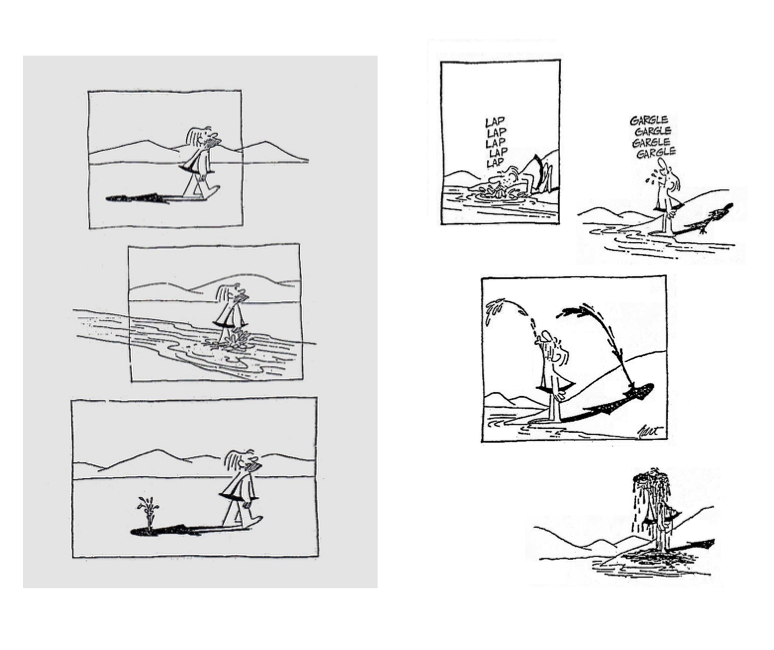

Incidentally, both the ‘Mordillo Tree’ being cut down, and the ‘Mystova’ in the mirror cartoons that we considered in the last section represent the extreme case of a VC twist, without any real imitation going on. They are what we might call ‘pure forms’ of that particular twist. True, they may carry a legit that takes the whole joke much deeper into Social Space as a by product, but as far as the actual twist is concerned, we are clear that their play is with Physical Space, and not with matters more human. Here is a reminder of what these two cartoons present us with.

Clearly in each of these two cartoons, the play is on visual correspondence, and this is actually quite a weak twist on its own, without the more interesting and additional option of an imitation twist being used at the same time. So it seems that cartoons, like those with the cavemen spitting water at their masters, are much more about the life of ‘shadow men’ than they are about breaks in VC that happen to then occur in the process. And it may turn out that when the shadow or reflection is that of a human being, then the twist is likely to be an emphasis on the ‘Image as Human’ twist, rather than simply being a twist on visual correspondence, because a reflection of a person doing its own thing is more interesting than the mere break in VC that it may also then involve.

Now let us look at an example that benefits from both a dramatic break in VC and a dramatic Image Imitation twist. An imitation where the shadows are depicted as humans in the middle of a dramatic contradiction with their originals, and indeed each other.

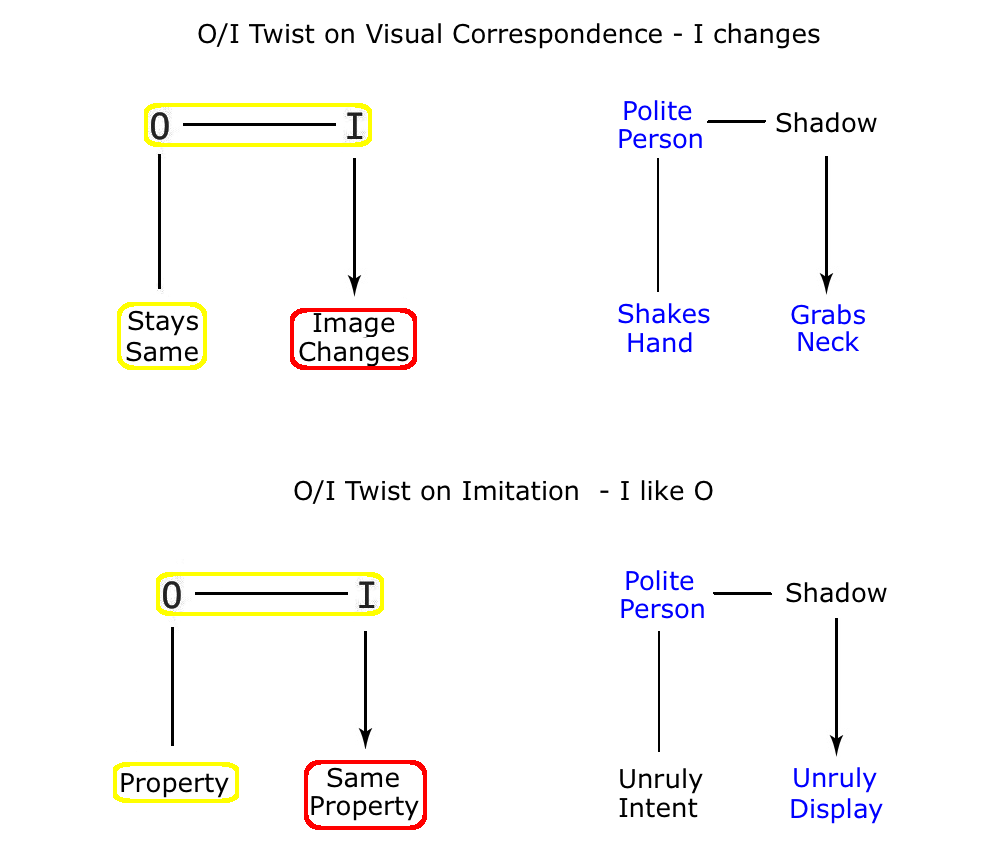

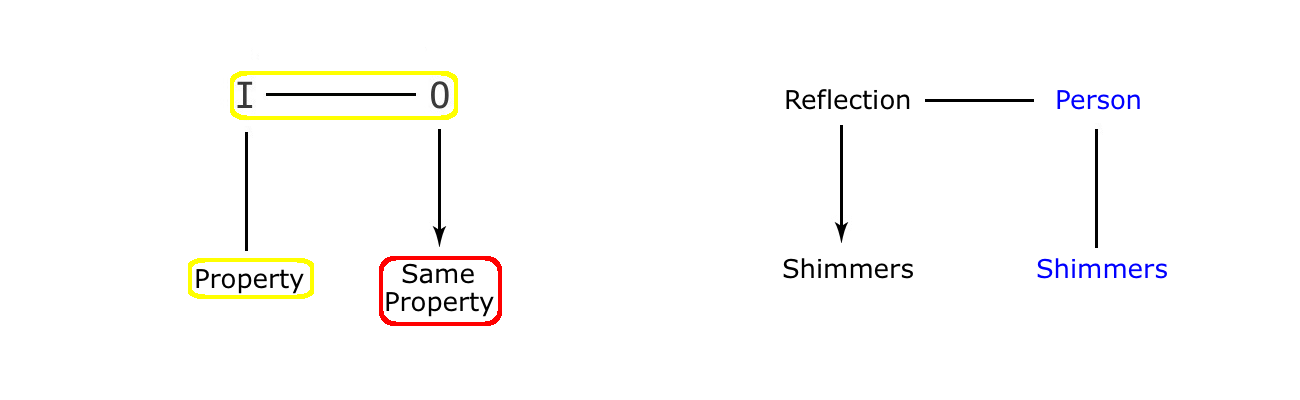

So what we have here is a serious visual break between the two men in the foreground, and their two shadows on the wall, making this a good example of a twist on visual correspondence. But at the same time, what we also see here is a serious break between the two worlds of social appearances and social reality. Because under the guise of an apparently congenial handshake, we discover that Mr Green would really prefer to strangle Mr Yellow, and the graphic depiction of the shadows leaves no room for doubt about this. (We might compare the use of the shadows in this example to the use of that common technique of the ‘subtext’, as employed so successfully for example in the Woody Allen movie, ‘Annie Hall’). Now, it is precisely this separation of the shadows from their casting originals in Physical Space that allows the cartoonist to demonstrate the duplicity of the originals in Social Space. The result is that we have two twists at work in this picture, and they work in a particular order, in that one is about a physical matter (a break in VC), that then reveals a twist about a social matter (a break in sincerity). As for the legit – we need look no further than the familiar fact that there is often a notable gap between social appearances and social reality. So here are the two twists in diagrammatic form.

The result is an idea that uses both the physically based twist of the ‘Image Changes’, and the socially based twist of the ‘Image behaves like a Human’ to create a combined effect that is rather more effective than the sum of the parts. After all, neither the break in VC, nor the anthropomorphic twist of Image like Human carry much surprise value on their own, being just too familiar to make much of an impact on us. But together they make a strong combination that carries the day. But the important point here what happens when the two are combined. Because generally, what we find in cases like this, is that as soon as the ‘Image Changes’ twist is applied to the human figure, then the ‘Image like Human’ twist is enabled by default. And once that happens, it is likely that this second twist ends up being just as important, if not more so, than the physical twist that began it all. This is simply because twists that involve Social Space are more intriguing and compelling to us than straight twists on physical reality. So the success of a joke it is not just a question of relative familiarity and surprise value – it is also very much a question of the relative degree of human meaning to be found in the different areas of logic that the twist may be playing with.

Coming back to the cavemen cartoons, where both twists are at work, which then is the primary twist? On reflection, it looks as if they are primarily an example of Image like Original twists, where the shadow behaves like a human being, stoically or petulantly spitting out the water it has swallowed, this necessarily resulting in a break in visual correspondence to boot. But the VC side of things is still important nonetheless. Indeed, if we look closely at the second cartoon, where the spout of water goes through the air to drench its owner, we find that, far from breaking the VC between man and shadow, VC is actually being used as the principal way of achieving the subsequent imitation twist. Because at that point where the legitimate shadow leaves the boundary line of earth and air, and becomes material (indeed liquid), it is the visual flow based on VC that enables it to reach into the air as a ‘reflection’ of the real gush of water, before it then plops down over the man’s head.

However, it is worth noting that in the third caveman cartoon, the logic is mainly about the issue of visual correspondence and the behaviour of shadows (‘I wonder where your shadow goes?’), putting this particular example firmly in the VC basket. Though even here, we see that serious value from the imitation side of things is added to the cartoon through the surreptitious way in which the shadow rejoins his master without his realising it.

So although we can leave those two cavemen cartoons as examples in the VC collection, they should really be the cartoons that introduce the imitation twist of ‘Image like Original’. But as long as we are clear about the inevitable overlap between ‘I changes when O stays the same’ and ‘I like O’ Imitation twists, then we can be clear about drawing the line between VC and non VC imitations, and recognise that the caps fit, but not always as well as the head would like.

The ‘Original Behaves like its Image’

In the normal scheme of things, objects don’t imitate their images, however slavish their image might be in copying them back. But here is an example of a cartoon where the twist does exploit a property of an image, transferring it to the nearby original for the purpose of the joke. So in this case, the twist is not exploiting visual correspondence, where the image is at fault, but is working the other way around, with the Original taking on an extra property – from its Image.

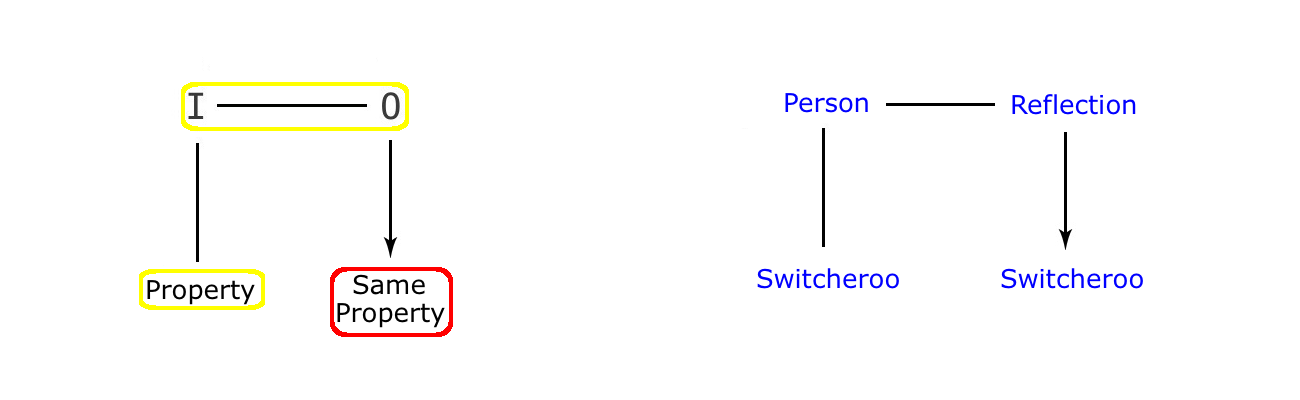

.jpg)

Notice that, in frame one, there is no reflection of the man in the water. And because the reflection is ‘off-stage’ (as in totally absent), it is not obvious that the man is standing in front of a stretch of water at all. Yet at some point, we will need to know that there is water at the foot of our standing figure, or we will have absolutely no idea what is going on here. So what tells us that an area of water, and therefore a reflection, is involved? The answer lies in frame two – where the ‘plop’ of the dropped object, and the ripples caused by it, make it clear that the man is looking down at a potentially reflective surface. This gives us the pair of clues (plop and ripple) that are vital to our seeing two important markers. One, that the man is looking at his own reflection – the plop, and two, that the nature of the property being exploited in the twist is that images can be disturbed – the ripple. Notice also that it is much easier for the cartoonist, Nurit, to make that clear with a pebble than with, for example, a breath of wind. This is because the pebble acts like a an on/off switch, making the change from flat to wobbly water in one immediate move. This serves the cartoonist well, as it is then makes sense to present us with a before and after frame – one on each side of the on/off switch of the ‘plop’. A set of points that emphasizes the degree of design in what is actually a deceptively simple cartoon.

So why is there no reflection of the man in the water to begin with? Surely that would get round the problem of having to do all of the above? Well, if we start at the end of the cartoon sequence, we see that there is also an absence of any reflection there as well. In fact, the only clue we get that the man is gazing down at a mirror image of himself comes from the dropped pebble, and the resultant and recognisable effect in the last frame of a shimmering man. And surely this absence of reflections in the water is not because the cartoonist finds the graphic presentation of a slanting reflection in the water too hard to manage? So perhaps there is some kind of advantage to this otherwise surprising omission?

To omit the reflections underneath our standing figure is of a positive benefit to the cartoon. Imagine that the reflections are put in place by an over zealous cartoonist. We would have a straight mirror reflection in frame one, a disturbed reflection in frame two, and some kind of a calming down but still disturbed reflection in frame three. And it is in frame three that we want to avoid any graphic reference to the image in the water, simply because to put one in is to lose the dramatic effect that we gain by showing the casting object shimmering away, on its own. An effect that also avoids the mistake of spelling things out too obviously, because it is always better to make the viewer put a little effort into the resolution of the joke. The puzzle effect adds to the power of the denouement in this case.

Another problem with this particular imitation twist is that we normally blame the image for any transgression between the two. Which means that if we see both the man and his reflection in the final frame, we might think that the image is copying the wiggly man instead of vice versa. But using this technique, where the image is omitted from the picture, we are clear about what is imitating what. Because what we see is the casting object behaving just like a well known property of a reflection in water. A behaviour we have been reminded about with the pebble in frame two.

Because if the coin is dropped, then we have to decide whether to make the casting figure of the man shimmer like his reflection in the water. Now if we do make him start to shimmer, we lose the nice on/off switch that the middle frame gives us, dividing the normal man from the shimmering version in frame three. If we do not, and keep the man as he is in frame one, then we introduce a break in visual correspondence in the middle frame. However, this VC would then be renistated in frame three, because the man is now shimmering in concert with his image below. As if there was a delay in the response of the man to the reflection’s activity perhaps. Which could make sense, it is true. But then it is nowhere near as dramatic as the off/on version that we see above in our finished cartoon. Because by omitting the reflections altogether, the cartoonist both clarifies and dramatises the twist for all that it is worth, giving us a narrative sequence that is as simple as it is compelling.

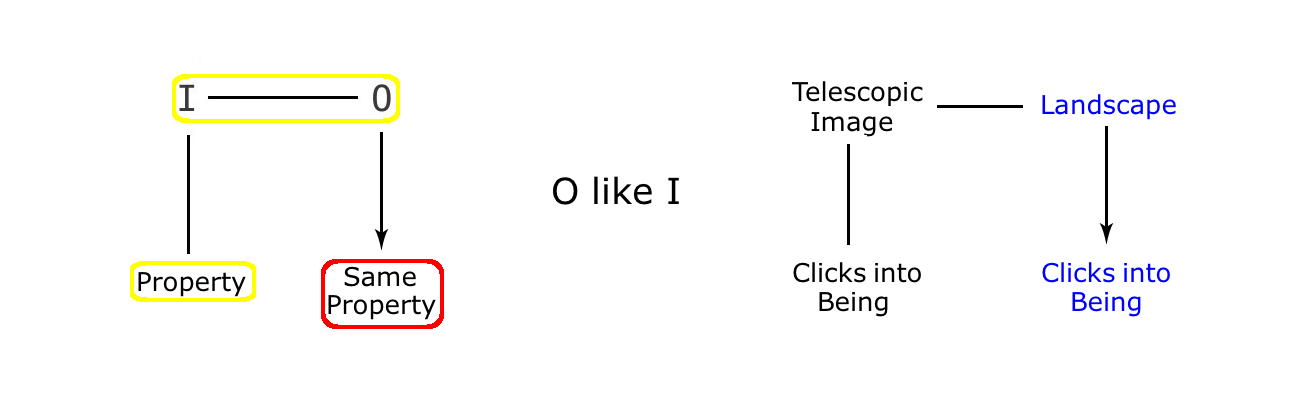

Here then is the semantic printout.

If we now compare how images imitate their originals, and vice versa, we discover a difference in action and substance. So, images naturally imitate their originals, and the image imitation twist happily exploits that fact by taking this just a little further. Making this an exaggeration rather than a reversal, because the logic points in the same direction, and the twist is therefore just moving things a little beyond the normal bounds. But when we look at the other way round, where the original imitates its image, things are a little different. Different because the ‘O like I’ twist challenges the asymmetry written into the physical laws of nature, where the direction of imitation between object and image is one way, and one way only. A challenge suggesting surely that this latter twist is more radical than the former ‘I like O’ twist. After all, physical objects exist without reference to their image, and pay no attention to them whatsoever – they do not naturally imitate their shadows and reflections. So for an object to take on a property of its image is unheard of, and goes totally against the grain of physical law. In addition, it is not just the direction of this flow of imitation that makes the ‘Original like Image’ the more radical of the two twists. It is also the fact that whilst images are fleeting and insubstantial, the casting object is solid and resistant to change. Because this makes any changes to the image easier to countenance, whilst changes such as the rippling of the man are less easy to sustain, and thus more radical. So that makes two reasons why the ‘O like I’ twist is more of a challenge to our normal perceptions, and presumably that gives this twist the edge when it comes to overall success?

These two factors of asymmetry and relative solidity present us with a good reason for that assessment. But is this all there is to it? Well, it looks reasonable of course, but then things are not that simple. Because inside the specific world of cartoon depiction, special conditions apply. So, for example, in a drawing, there is a striking visual symmetry between the original and its image, and this is clear to see in any cartoon where both are depicted as two dimensional drawings. A graphic point that makes the two seemingly equal, whilst in the real world, they are qualitatively different realities. In theory then, we can see that the one twist is more radical than the other, but in practice, the visual presentation wipes out such differences because both forms are made equally real in the world of the 2D drawing. Which makes it hard to argue that one is more amusing than the other because it is more dramatic. In which case, we might have to concede that imitation works equally in either direction, despite our suggestion to the contrary.

It is important to assess the relative strengths of different but comparable twists, but in practice, it can also prove very difficult. Difficult because although the weight of physical reality might seem critical in our assessment of what is possible, it seems the weight of such an apparently trivial factor as the two dimensional representation of an original and its image can easily push the balance the other way. But this is the power of Social Space, where we know that meaning can trump reality time and time again. Nor should this come as any surprise. Because we all know that we are experts at holding beliefs completely at variance with the physical reality around us. So the earth is flat, the sun goes round it, there is life after death, and there is at least a reasonable chance that we will win the lottery, to mention just a few examples…

In our next example, we find another imitation twist of the same type, and again it uses a reflection, but unlike the last cartoon, where the image is lying down, we see this time that the reflections are vertical. This is relevant because in reality most images are horizontal, but vertical images are probably preferred by the cartoonist because they stand up, visibly playing their part in the real vertical world of human beings. Additionally, drawing an image that is lying down, and not full face on, is trickier for the cartoonist, which is one reason why Nurit may have been happy to avoid it altogether in the cartoon we have just looked at.

In fact, when we think about it, most cartoons view their subject transversely, looking across, and sideways at us, as vertical entities, rather than from above or below. Clearly, there must be a good reason for this. So is it because we ourselves spend most of our time looking Outwards rather than Up or Downwards (though we can do that too of course, and so can cartoons)? Well, this does seem to be the right answer to this question. We might say that our view of the world is ‘Sideways On’ (that is, we tend to look at the front, back and sides of objects around us). So it is only when we are lying on our backs, looking up at the sky, or bending down, and looking at the ground, that this habitual view changes. Indeed, a quick survey of the shots in any photo collection will show us the same pattern. Because there we see that ‘birdseye’ and ‘wormseye’ shots are surprisingly unusual (despite the modern delight with drone cameras) and in fact we tend to point our cameras outwards, in just the same way as we look outwards. But perhaps elsewhere in the universe there are intelligent beings, hawk-like in form, that spend most of their time looking down, in which case it would be interesting to look at their cartoon drawings… (though there are grounds for suspecting that, even there, much of their art and othewise would be sideways on).

Anyhow, in this next cartoon, the view is, predictably, from the usual human angle of sideways on.

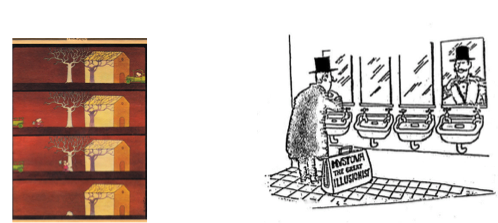

The first thing to notice in this cartoon is that it uses not one, but two human figures, and there is good reason for this. We see two people go in to the hall of mirrors, and it looks as if the same two come out again. This gives the cartoon an advantage, because it looks as if nothing has changed. The point being that if only one figure is shown going in and out, then the difference, and thus the twist, would be immediately obvious. But when two go in and out, it is easy to miss the switch because the pair is still short/fat and tall/thin, just as they were on entry, and these are the properties still evident on exit. The upshot of using two figures is therefore that we have to cast around for the twist when we first look at this cartoon. And by making us miss the all important switch, even if only for a moment, the cartoonist is adding a puzzle element to the joke. Which makes the result more interesting because, as we know, a joke is worth more if the onlooker has to put a moments effort into its resolution.

The resolution we come to shows us that the cartoon figures have swapped their visual identity. So how can that be? Well, the pair of reflections in the distortion mirrors leaves us in no doubt. Clearly, the originals are now behaving like their images, left behind in the hall of mirrors. Which makes this another imitation twist, where the original takes on the properties normally characteristic of its image.

Note too that this sequence of events has to be presented in a number of frames, just like the ‘Shimmer’ cartoon by Nurit. For how else can we move from frame two, in which all is normal, to frame three, where the switch has been made? Indeed, it is only by keeping a gap between the normal and twisted versions that we keep it clean, and happily, their leaving the hall makes this easy to do. One moment we see the twisted forms in the mirrors, and the next moment, we see the result, thus avoiding any confusing transitions along the way. Neat (and we have to leave the reflections behind in the hall, so not just neat but necessary). Notice too, that unlike the previous example, this one features all four elements of the twist, all of them front of stage in this case. Mirror, reflection, originals and changed originals are all there. This is because all four are vital to the denouement in the cartoon, and the before and after progression is not possible without a clear reference to the stages in what is essentially a causal sequence. However, in the Person Shimmers cartoon, we do not see all four participants, because the dropped pebble does the same job as the explicit show of reflection inside the hall of mirrors. The point being that it does so in a subtle way that leads to the end frame giving us a surprise. Whereas, in the Hall of Mirrors cartoon, things are somewhat less subtle, and somewhat more spelt out. Because the reflections have to be explicit in this case, to lead directly to the changes in the originals (their distorted shapes are so specific that some reference to them is essential, whereas the generic ‘ripple’ in the previous cartoon is well understood). But there is some compensation in the fact that the cartoon uses two figures instead of just one. Because at least there is a puzzle element to balance the more heavy handed ‘telling us how it is’ of the causal narrative, so perhaps we can see a light touch after all.

The fact that such a ‘Hall of Mirrors’ is, or at least was, so a popular is testimony to how we humans love to play around with images, and especially with reflections of themselves. And to make an apparently banal point about the use of distortion mirrors: if normal mirrors had been used, the imitation twist would have died stillborn, because then the normal state of affairs, where originals and their images look exactly like each other, would have led nowhere. Or, to put this another way, the image maker has to be different from the normal source of mirror image, because only then can it impose that difference on the original to make this twist work. And as we shall see below, in other examples of this twist, image makers are a useful tool in the engineering of this particular twist.

Where then is the legit to this twist? Well, certainly the mirror is the ‘guilty party’ in that it seems to have caused the distortion. But distortion mirrors are nothing new, and this hardly explains how the laws of the universe have been so radically changed as to morph a couple into the almost entirely reconstituted forms we see coming out of the exit. So does the presentation of this scene through the 2D medium of the cartoon help us to believe in what we find here? Well, actually yes it does, because in real life, the human figures would be in full 3D, but here they are already depicted as 2D beings, putting them on the same level as the reflections in the mirror, and thus making both sides of the O/I relationship equally real. This makes the switch easier to pull off as the main asymmetry of ‘solid versus flat’ has been removed, making the changeover visually legitimate at least.

But it is also the ingenious balance we gain by having not one, but two, figures involved in this picture that is really useful here. Because by putting a pleasing symmetry into the exchange, the switch looks equally balanced on both sides. Two go in, and then two come out. It is just that their bodies have been switched around in the process, but it all adds up to the same total, and that seems to help us accept the denouement quite happily. Which sort of makes sense because there is balance in the exchange, and our suspicions are therefore allayed long enough for the cartoon to achieve its momentary effect. And if we then add to this the ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ that occurs every time we look at a cartoon, along with the familiarity of yet another example of imitation, then I believe we need look no further. Because we can see why the cartoon is credible.

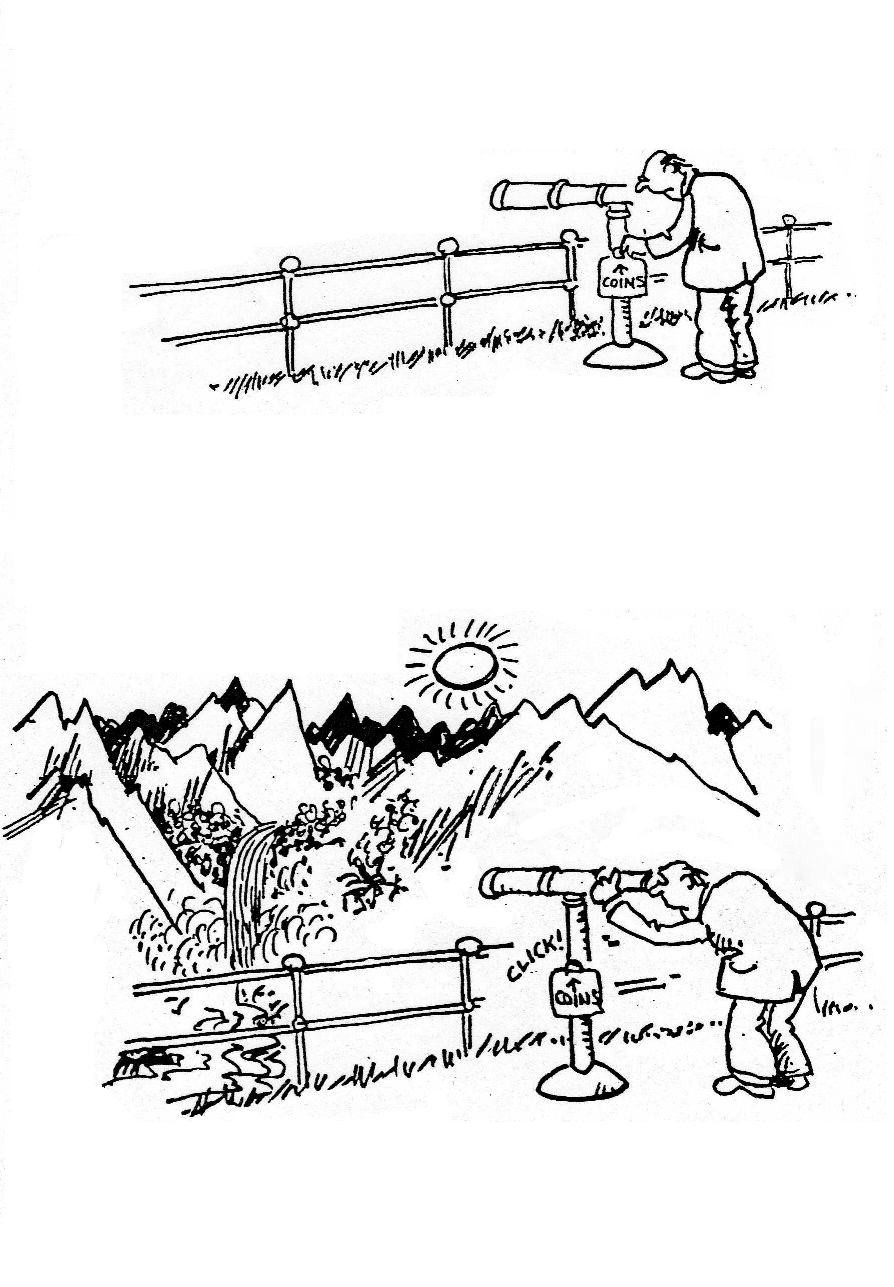

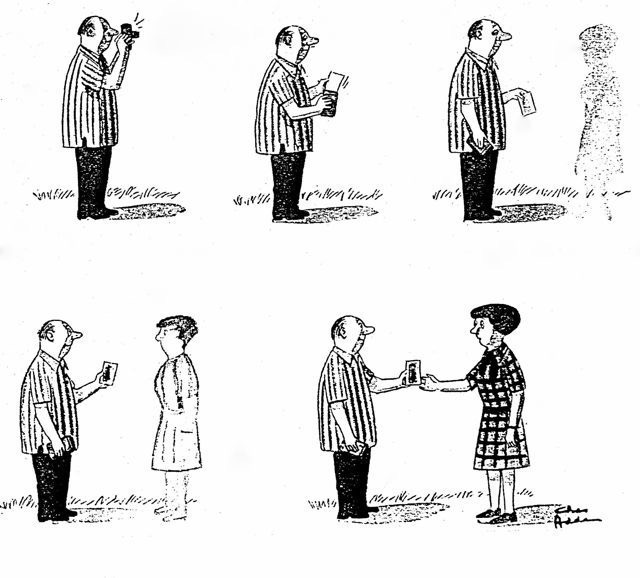

In the next example, we come across a joke idea where again, it is the image maker that provides the critical property for the transfer to the original. Now, we are all familiar with the idea that when the object is absent, the image is absent too, but here, it is the other way round…

A real landscape does not come into being with the click of a coin. Yet here we see a real landscape click into being the very instant the telescope is switched on. Which means that this particular landscape is behaving exactly like its coin operated image, clicking into being only when its image appears inside the viewer of the telescope. Which is to say that it is an original behaving like its image, so that it is only present when the coin is active, and absent when the coin’s value has expired.

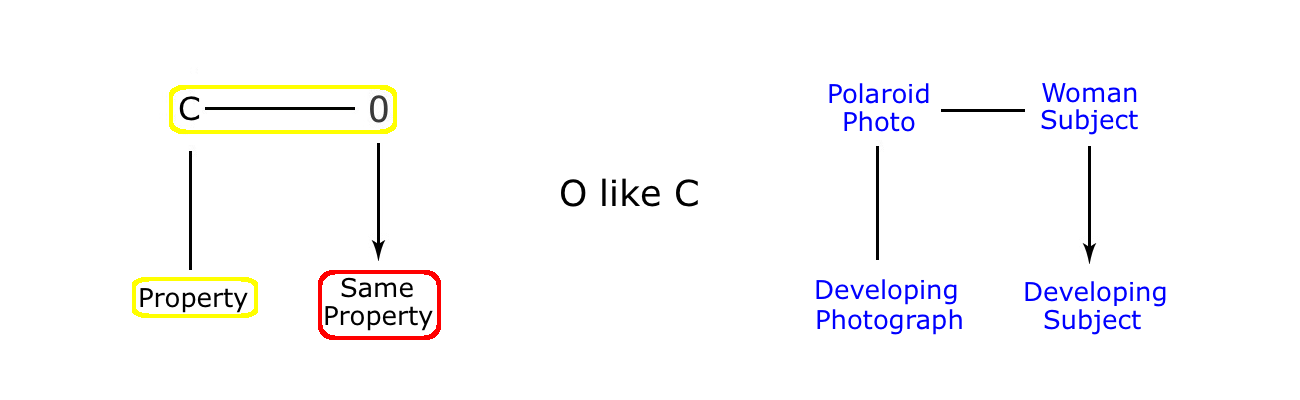

Interestingly, just such a twist example exists in the Original/Copy relationship. In this case, it features a Polaroid camera, where the photograph develops before our eyes, in classic Polaroid fashion, clearly visible in the hands of the photographer, and just as we would expect. But at the same time, the original figure that is the subject of the camera also develops into a firm representation that at first was invisible. As we see here:

In this case, the figure of the woman is behaving like the copy, developing into a visible form before our very eyes. And in this cartoon, we actually get to see the copy as well as the original (unlike with our telescope example, where the image inside the telescope is impossible to get a look at). So is it important that we see the copy in this example, when in the previous cartoon it is probably best we do not see the image? Well, we have to be clear in our minds that the camera is indeed a Polaroid, and not just a normal camera, so to that end, the print has to be pulled out and held up whilst it develops its photo. However, what we do find is common to both cases is that the image or copy are absent from the scene, up to the point where they then reappear when the right image or copy making technology is properly activated. But then the cartoonist has what amounts to magic powers in order to achieve this, because keeping the scene clear of either a huge landscape, or an individual standing right in front of us is all standard stuff when it comes to the full power of the copy. Here then is the diagram of the O/C parallel to our O like I twist.

But hold on a moment. Surely the telescope in the case of the landscape cartoon is a copy maker, and not a maker of images? In fact, surely it is just like a camera? (After all, it does look suspiciously like a camera, and we see no mirrors, nor indeed any reflections in this cartoon). So how can we tell the difference? Well, the test is a simple one. All we have to do is check whether the image in the telescope viewer changes when the original changes. And we know it should because we know that when for example a bird flies past the telescope, it also appears in the telescope viewfinder. Which means it must be an image, and not a copy (it is a reflection to be precise). A reflection that comes from a series of lenses and mirrors inside the telescope. Which admittedly seems similar to a camera, but the whole point of a camera is to make a copy, not an image. (Both the image maker and the copy maker use mirrors to help create the image or copy they are designed to supply us with, so both work through the use of reflections even though the camera ends up with a rather different result).

Actually, what the camera does is to take possession of an image that has been directed and reflected through its optics and mirror, to then turn it into the unchanging copy that we call a photograph. This means that its purpose is quite different to that of the telescope, where a constantly updating real time image is what counts to its owner. So the camera is there to freeze time and store it as a copy that is then independent of its original, and the telescope is a tool to be used in real time, with its main purpose being its greater optical reach over our weak human pair of eyes.

So, the Telescope cartoon does involve an image twist, and is directly comparable to the Polaroid cartoon, where the original gradually fills in, just like its polaroid copy does. The difference being that in the Telescope cartoon, the change is rather more dramatic, appearing from nowhere, just as its image does inside the telescope, with the click of a coin. And apart from that, the two cartoons are very similar: an ‘Original Like Image’ twist in one case, an ‘Original Like Copy’ twist in the other, with both using the same kind of property, namely an attribute of their image or copy maker.

Returning to the Landscape Appears cartoon for a moment, we can see that, just as in the Nurit cartoon where the ‘person shimmers’, the original is the only side of the relationship actually present in the cartoon. So we see the landscape, when it appears, but no attempt is made to show us the image that must be there, in the viewfinder of the telescope. And part of the reason for this is practical. Because it would be hard for the cartoonist to show both the wide angle view of the landscape and the zoomed in view of the image inside its viewfinder at the same time (though a multi frame cartoon could get past that particular visual obstacle). But there is another factor here as well. Because the appearance of an image in the telescope at the same time as the real landscape would diminish the dramatic, sudden, and singular appearance of the original landscape in frame two. So, either way, it seems that, just as in the Nurit cartoon, an absent image does no harm to the presentation of the twist, and actually helps in the subsequent dramatisation of the imitation twist.

Finally, a point about the legit for this cartoon. The property that this twist uses as its fulcrum is the dependency of the image on a coin payment (without which the image is blocked from view). So the twist consists of blocking the original landscape from our view, and then bringing it back at the moment the coin is inserted into its slot. Or, to put it another way, the original is removed, and then allowed to reappear. Now this is a radical move being presented to us by the cartoonist. Because just as the initial absence of the subject in the Polaroid example amounts to rather more than a sleight of hand, the complete absence of the landscape in frame one is a complete attack on our normal experience and expectations. Fine, we can understand if the landscape is far away, or if its details are blurred by distance, but at least it has to be there in some form or other. But for it to suddenly appear out of nowhere, at the behest of a pay telescope, is clearly a dramatic attack on reality. So where, we must ask, is the legit for such a twist? What makes us accept this cartoon so readily when its logic runs directly counter to our knowledge of Physical Space?

Surely in this case, it is the visual authority of the cartoon drawing that makes us willingly accept this otherwise major transgression? Because when we actually see what happens – it takes place right before our very eyes – we find it easy to accept. We don’t have to imagine it, or make any effort to visualise it, because it is right there, staring back at us, so our only effort is directed at understanding the joke, rather than challenging its veracity. And the two frames clearly show the before and after, and the cause and effect that makes up the narrative sequence, so even there, little effort is called for. So this is simply another case of ‘What You Get Is What You See’ (WYGIWYS) then.

But there may be more to it than this. The thing is, we know that telescopes bring a far-off reality into being, where before there was just a blur. And it is true that the power of such image making tools as the telescope and the camera are tantamount to a very special form of magic. After all, the reason everybody loves looking through a telescope, zoom lens, or down a microscope is precisely because of these amazing powers of revelation. Special powers that naturally lead us to expect further magic. Which is exactly what we get in the two cartoons above, where our very existence is only clicked into being by the machines we use to view it in the first place.

On a more general point now, it seems that if we look closer at the representation of the Original like Image twist in the cartoon literature, we find that there are rather fewer examples than we might expect, and there is indeed a reason for this scarcity. A reason that has to do with the relative number of properties on either side of the Original/Image relationship. Because whilst images themselves do not have many special properties to offer a casting object, the material world that supplies the image world with its casting objects gives the valley of shadows and reflections a veritable wealth of properties to imitate. All of which makes it inevitable that any cartoonist looking at an object and its image, and searching around for properties to act upon to create the leverage for a joke, will opt for the easy-to-be-had characteristics of the original casting object. And if those properties are not to his liking, it is then quite easy to bring in a whole new raft of characteristics by changing the object itself. That is, casting objects can be changed ad infinitum, but when it comes to the image, well, firstly there is only a choice of two kinds, the shadow or reflection, and secondly, there is only a limited list of properties to be played with between those two categories.

What then is the pool of image properties open to the ‘Original like Image’ twist? What sort of properties can the original take on to create a twist where the object imitates its own reflection or shadow? Well, given that the image depends for its existence on the source of light, the nature of the surface, and in some cases, an optical device for transforming those images, as well depending on the casting object itself, the list must derive from those four conditions.

1) Casting Object. From the casting object come all the properties of that object that either a shadow or a reflection are capable of picking up. But it is hard to imagine how this particular set of properties could be used to create humour sofar as the ‘O like I’ twist is concerned. After all, an imitation twist where the original takes back exactly those properties that belong to it in the first place will simply end up looking as it did before, showing no obvious change. And no change means no twist.

2) Light Source. The light source can be present or not, and when it is present, it may be strong or weak. It can also come from a variety of directions, and will vary in duration. The image is a slave to the light source, and this results in such familiar properties as the shadow extending out horizontally on the ground when the sun is low, or there being multiple shadows due to multiple sources of light. These are properties that emerge as a special set of characteristics of the image, making them properties that can be taken up by the original to create a twist. But in the case of the reflection, it is really just a question of whether there is enough light or no, because although the direction of light source can make a difference to the image in the mirror or water layer, it is the same difference that we see in the casting object.

3) Surface. From the surface come the distortions born of the shape and quality of that surface. The ecology of the reflection is restricted to only two environments, these being mirrored surfaces and stretches of water. However, the territory of the shadow forms a far greater domain, featuring as it does the terrestrial topography of the planet. So shadows enjoy a freedom that is, so to speak, the envy of the world of reflections. On the other hand, reflections enjoy a level of detail that the shadows must envy. But either way, distortions in the image can arise from a still or moving surface, depending on factors such as wind on water, or uneven glass and ground. So again, these are properties that can be taken up by the original to make an imitation twist. Which is what we see in the example of the figure standing in front of the water, and shimmering.

4) Optical Devices. Image makers can supply the imitation twist with a variety of properties. Image makers such as telescopes, binoculars, microscopes, cameras, video cameras, magnifying lenses and computers; all of which do a variety of physical things, such as click on and off, zoom in and out, develop, overheat, magnify, diminish, duplicate and so on, so contributing many properties towards a potential imitation twist. Thus image makers supply the humorist with a veritable list of new, and industrial age, properties. All of which makes this one of the lists to go for if creating ‘O like I’ twists is your goal. All the more puzzling then that there is a lack of such examples in the cartoon literature…

To conclude then. Jokes that rely on the original imitating its image are limited by the range of properties displayed by that image, and that range is small. Which is surely why most of the twists on the Original/Image relationship are about the image breaking with its original, rather than other way round.

STOP PRESS

Have just discovered a youtube video that features a splendid practical joke involving several pairs of twin actors, and a number of hapless members of the public in a ladies washroom. The idea being that there is a piece of glass masquerading as a wall to wall mirror, with a replica of the washroom behind it. So all it needs is a double of the lady at the sink, acting exactly as she does, in mirror reverse mode, and the illusion is complete. So when an unsuspecting member of the public comes in, they see what clearly does look like a mirror image, and then get thoroughly confused by their own lack of reflection. Meaning that the double of the original, who is also a real person, and therefore a casting object in their own right, is behaving as if they were the shadow of the person on the foreground side of the supposed mirror. That is, we are clearly talking about an original behaving like its reflection, by duplicating every move that its purported casting object is making.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qW_gKJzJKNw&t=140s

The video has to be watched to be believed, and there is always the possibility that the so called ‘unsuspecting person’ is really a stooge, but that is not the point as far as this analysis is concerned, because either way, more than three million people have found this entertaining and believable, and if they really are stooges, they are excellent actors. More to the point, the surprise of the ‘victims’ and the cleverness of the duplicity make this very compelling, and when the twin pair finally break off the act, and starting moving independently of each other, causing another surprise because now there is a break in visual correspondence between the two, we have to slowly shake our heads with delight at the scale of this practical joke.

Now we move onto a graphic narrative, which features the shadow world rather than that of reflections, to identify the twists and turns taken by the characters in a cartoon story of some interest.