Today, I want to take you on a walk. In this case a guided walk. Guided because we are venturing right off the edge of the map into a landscape uncharted by science. In fact we are going ‘off grid’ and into a terrain where the laws of the physical universe are suspended in favour of a totally different logic. Namely, the rationale and fantasy world of the human imagination.

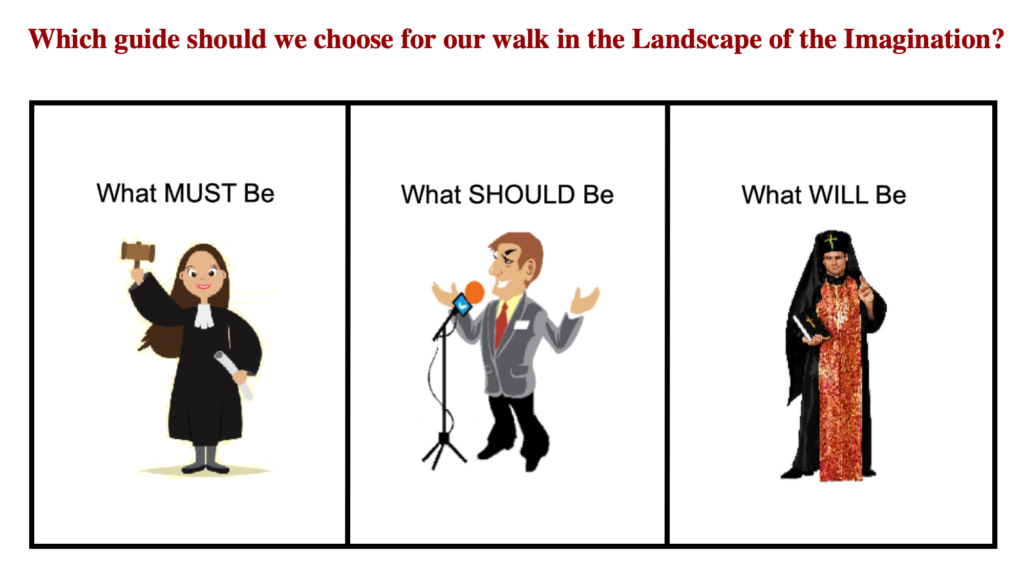

But before we start, I should tell you it’s not me that’s going to be our guide on this walk. I’m merely the guy who has sketched out a rough plan of where we’re going. A plan based on a two areas I think might prove interesting to explore. However, finding a good guide proved to quite a challenge. For example (and to show you what I mean), let’s check out these three potential candidates below.

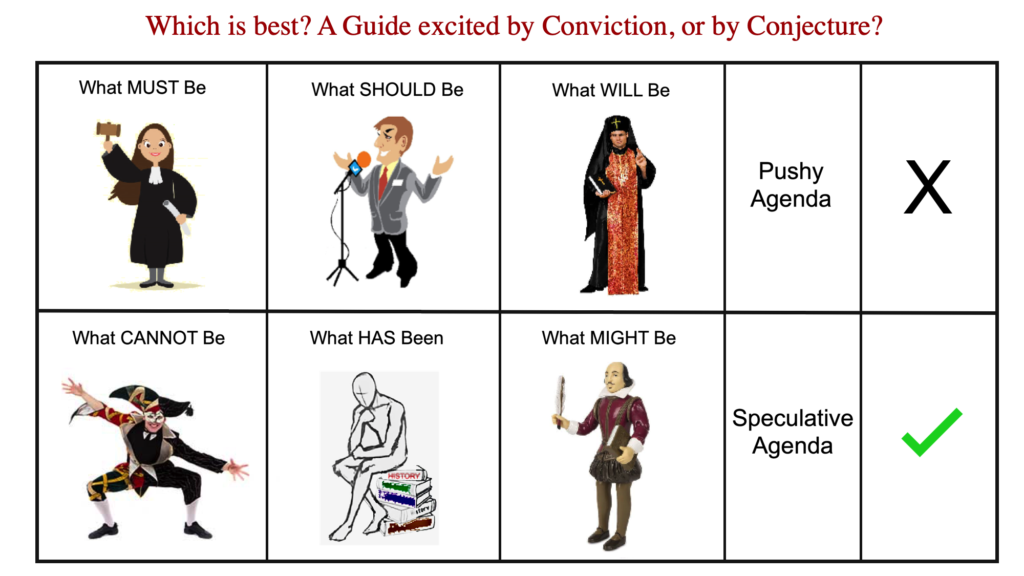

Lawyers, politicians and priests are all experts at navigating our world of human meaning, so could one of them be of help? Hard to imagine any of these as an objective guide though. The problem is they are somewhat partisan, and come with a pushy agenda. So can we find a more relaxed and also more detached guide perhaps? Well, how about one these three?

A historian might be a good guide, although our walk is small scale, and hugs the present. But what about the poet and dramatist, here embodied in the figure of Shakespeare? Well, a writer would make a cool guide, not least because of their excitement with the world of ‘what might be’. While the jester goes even further than this, routinely taking us into the absolute extremes of what might be, and this despite our knowing that it certainly cannot be.

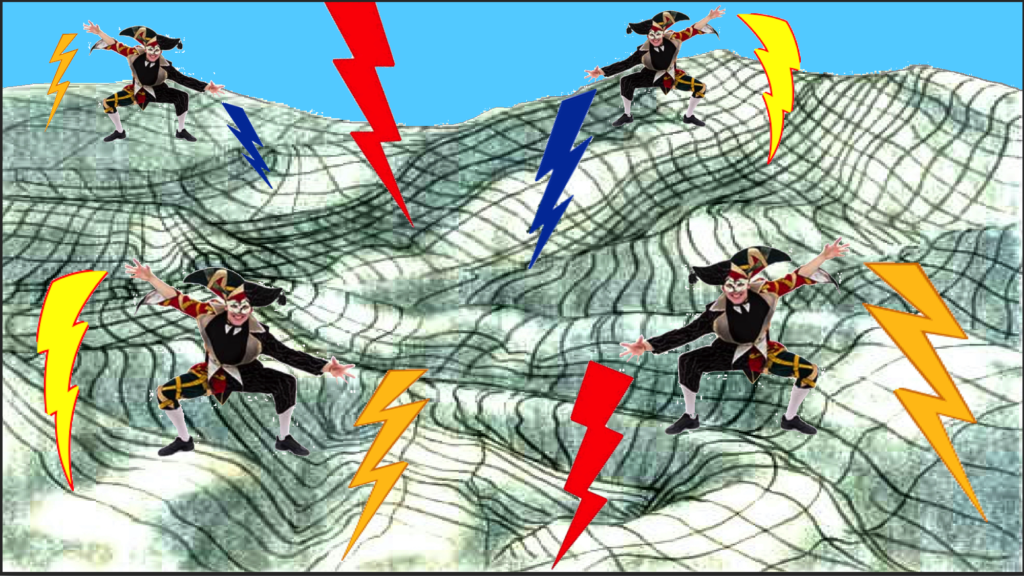

But then I’m not seriously going to choose the jester for our guide to the landscape of the human imagination, am I? After all, humour is an intrinsically tricky area, full of non sense, ambiguity and contradictions. I mean, we all know how hard it is to pin down jokes, so to opt for a jester as guide is an odd choice surely?

Well, there is a good reason why humour is tricky. The thing is, although the jokes that make up the jesters chosen language are easy to enjoy, they are actually very hard to read in terms of what they tell us about the features of the landscape around us. So, although humour is hugely insightful about our world of meaning, gaining access to that insight in a way that helps us on our walk might pose a real challenge. In effect, it will mean cracking the secret code of the joke, and that has never been done before.

However, even a brief look at how jokes work will show us why humour might otherwise make a perfect guide for our walk. The thing is, jokes twist the contours of our normal human logic into new shapes and alliances, and in so doing, they silhouette what we normally take for granted. Which is really helpful, because by doing this, they actually expose the underlying topography of meaning, at least for the brief moment of the joke. Which is why just this feature alone gives us a very good reason to choose the jester. As long as we learn how to break that code as we go along that is.

Our guide to the human world of meaning is therefore going to be humour, which should be fun. But what part of the human landscape of the imagination are we going to explore? Well, we need to bear in mind that the landscape of meaning is a jungle of great complexity, and that we need to begin someplace simple (preferably a place with good views). Which means we want to avoid precipitous climbs, dense undergrowth and areas of territorial dispute for a start. And given that meaning is largely a virtual reality, it might be helpful to start off by looking for some relatively solid stepping-stones. Meaning we need to find an area of meaning that has a physical foundation.

So here is the plan. We visit two areas of meaning that have their feet in the physical world. We will call the first of these areas ‘The Copy Plateau’, and the second one ‘The Valley of Shadows and Reflections’. Fortunately, these are areas much visited by cartoon humour – partly because being physical, they are easy to represent visually. So let’s take our first step and choose a cartoon for our very first orientation in this walk. We begin then with an example that draws its meaning from the logic and natural history of the Copy Plateau. With the understanding that if we can crack the joke inside this cartoon, we can learn not only about humour, but also about the creative logic that shapes the contours of the Copy Plateau.

In this cartoon, the wig copy is made to take on what might be called the ‘negative properties’ of the original head of hair. Human hair goes grey, and begins to fall out, and the wig was invented to circumvent these limitations. In fact, the wig is just one of a huge family of physical copies made by us humans to sidestep the physical limitations of the world around us. But in this cartoon, and by imposing these unwanted and negative properties on the wig, the joke calls the whole copy identity of the hairpiece into question, resulting in a radical twist. Radical, because it is one thing to make a copy imitate an extra property of its original, but quite another to make the copy imitate the very property the loss of which is the reason for the copy’s existence to start with.

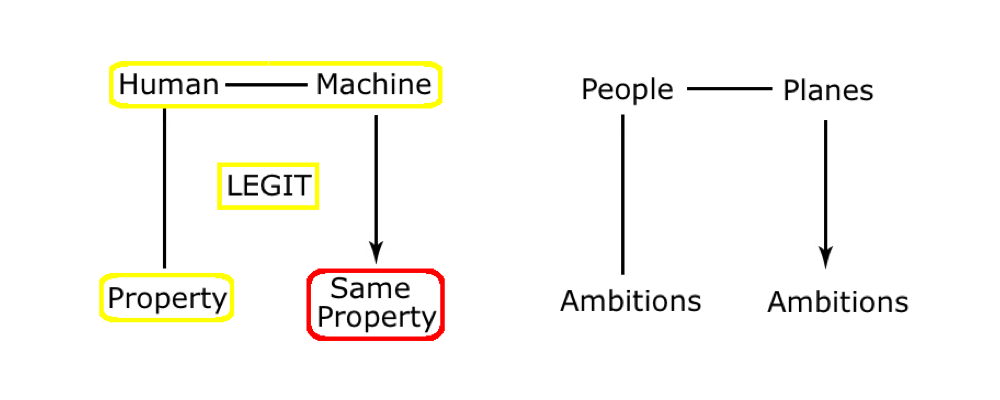

In the real world, the customer would surely refuse to go for this ‘something new in a wig”, despite its admittedly increased authenticity. But what about us, the onlookers? Do we buy this idea? Well strangely, yes, we do. With one important proviso that is. Which is that we always look to see if the humorist has offered us anything extra that supports the twist. Anything that is, which gives it some sort of sense and plausibility, even if that support only extends for the moment of the joke. Because although we know to make allowances for humour, we still expect a measure of argument that can help us take it seriously. Enough support that we can then laugh at it at least. So although we accept that jokes twist reality, we prefer the twist to have some kind of a claim to legitimacy, even if it is only surface level, so that we can enjoy the humour properly. Well, we can call this additional dimension of the joke the ‘legit’, but what and where is the legit in this cartoon? In particular, how does this legit then support the fairly radical twist between the Original head of hair, and its wig Copy?

If we look at the context of this twist on Original and Copy, we see that it consists of a visual and verbal reference to the world of salesmanship. A world that frequently produces ludicrous claims in its ostensible drive towards the greater authenticity of its products. Now, the claim in the caption is that ‘It’s something new in a wig’, to which the rationale is simply that the more the wig imitates real hair, the better it must be. (A fundamental tenet of copy logic is that the more the copy looks and acts like its original, the better it is). So the salesman is merely pursuing this logic of copying fidelity to a point where it leads to a conflict with the logic of copy advantage (where the whole point of the copy is that it frees itself of some of the critical properties of the original). An example then of the zealous over-reach of the retail sales world.

The choice of the winning face of the salesman contrasts strongly with the baffled expression on the face of the customer and helps to support and dramatize the lunacy of the twist in graphic form. The cartoon medium always has that advantage over the told joke: the visual authority of the picture is a powerful way of supporting a twist even when no legit is present. Note also that the legit is carried in the caption, and that this is frequently the case in cartoon humour. Why might this be? Well, the legit often refers to a context far outside the immediate situation of the twist, and therefore too far away to be included in the same picture. Whereas the caption, which is usually in the form of speech for greater dramatic authenticity, can carry a reference to anything that language can stretch too. Including many abstract situations that elude the power of graphic representation. So the caption is a major asset in the presentation of the legit.

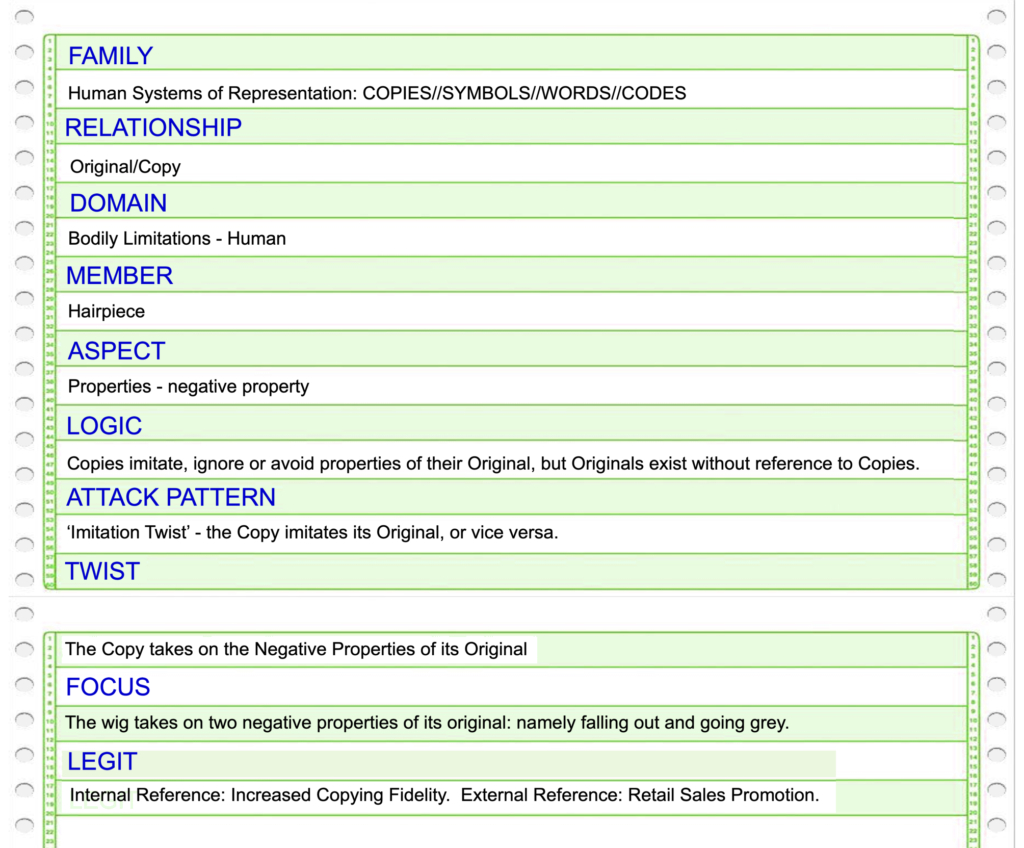

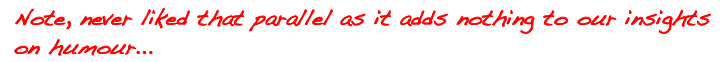

The dynamics of the wig cartoon can be summarised in two ways. As a listing, or as a diagram. For example, here is a sample listing of the kind that we might expect a computer of the future to spew out. I can almost hear the clatter of the printer (although printers may be a thing of the past by then).

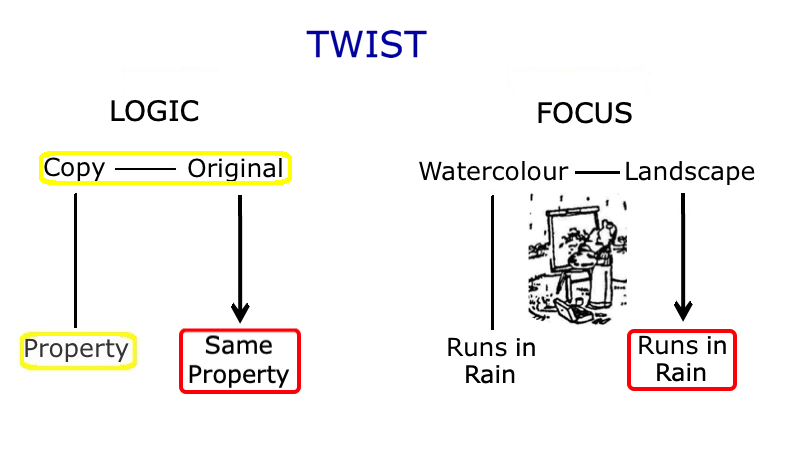

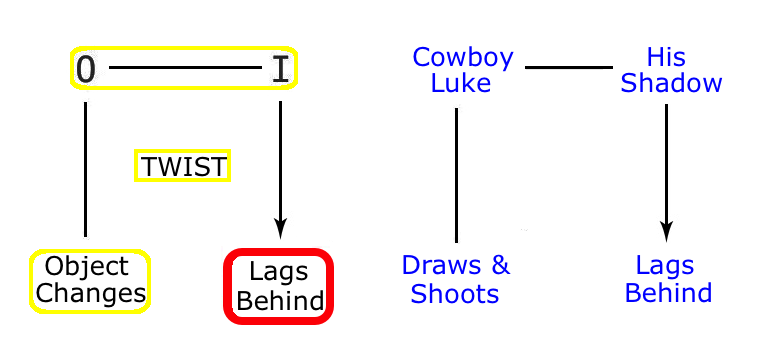

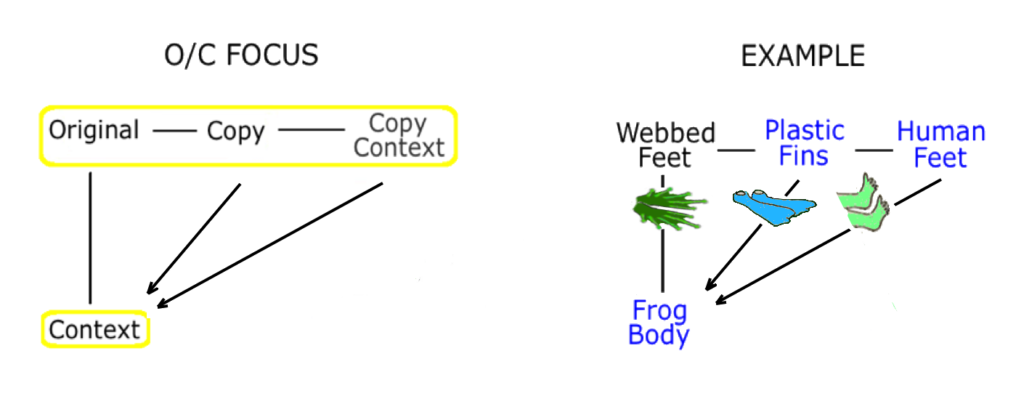

A second way and simpler way to capture this joke idea is with a diagram. Here is one showing the two main dimensions of the twist and the legit.

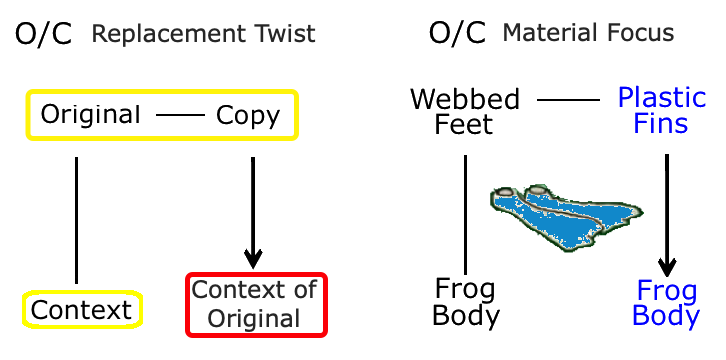

To summarise this first cartoon then, we are looking at just one example of a relationship (this one between Originals, and their Copies), one specific twist (in this case an Imitation twist, where the Copy takes on further properties of its Original), and effectively a double legit (internal reference to copying fidelity, plus an external reference to sales). But this is just the beginning of our journey, because this area of the landscape of the imagination is a favourite of habitat of humour, and if we walk further, we can find many other cartoons from the same family of O/C twists along the way.

But before we move on to the next cartoon, let’s just see what progress we’ve made with our first foray into meaning. So, firstly, and after just one cartoon way-marker, it looks as if we are already deep into the landscape of meaning, having identified our first step onto the Copy Plateau. It also looks as if we are learning as much about our guide as we are about the terrain our jester friend is leading us through. For example, we can see that jokes feature a ‘twist’, and that for us to enjoy that twist properly, the cartoonist must provide us with a form of legitimacy, or ‘legit’, that paradoxically allows us to take the joke seriously. The question is, could these two supposedly ‘key’ concepts provide us with a way to unlock other, and maybe even all jokes? Well, all we can say at this point is that we will put this model to the test repeatedly as we pursue our walk.

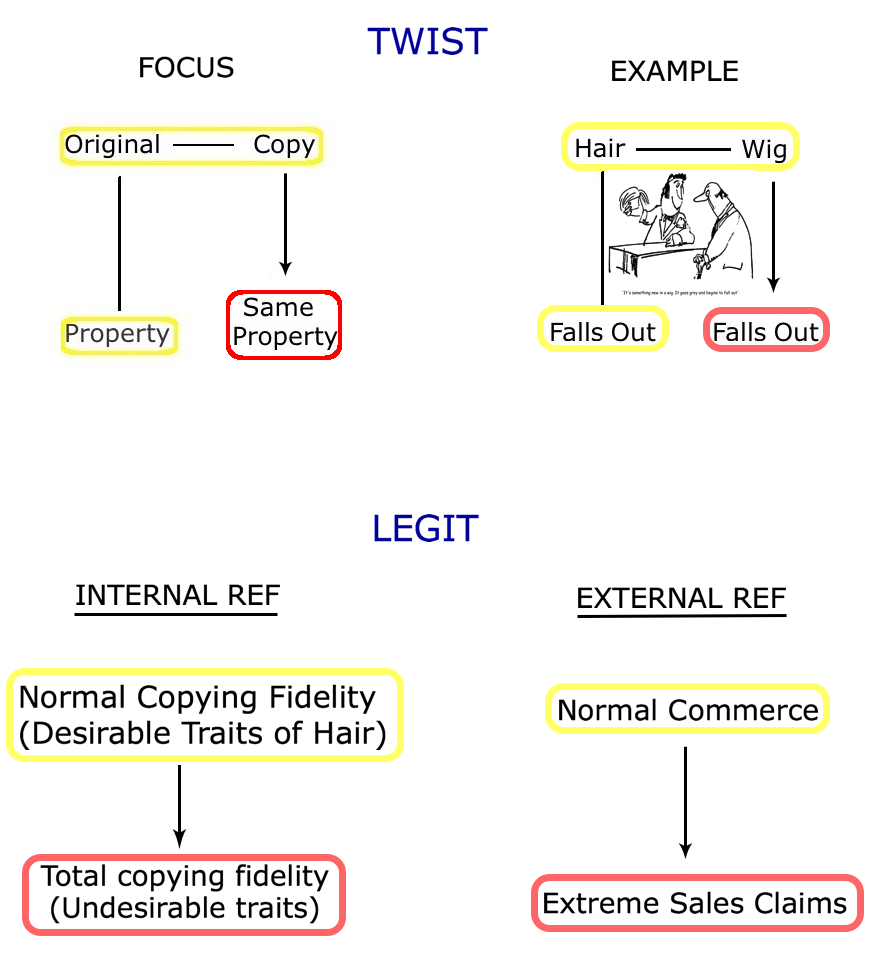

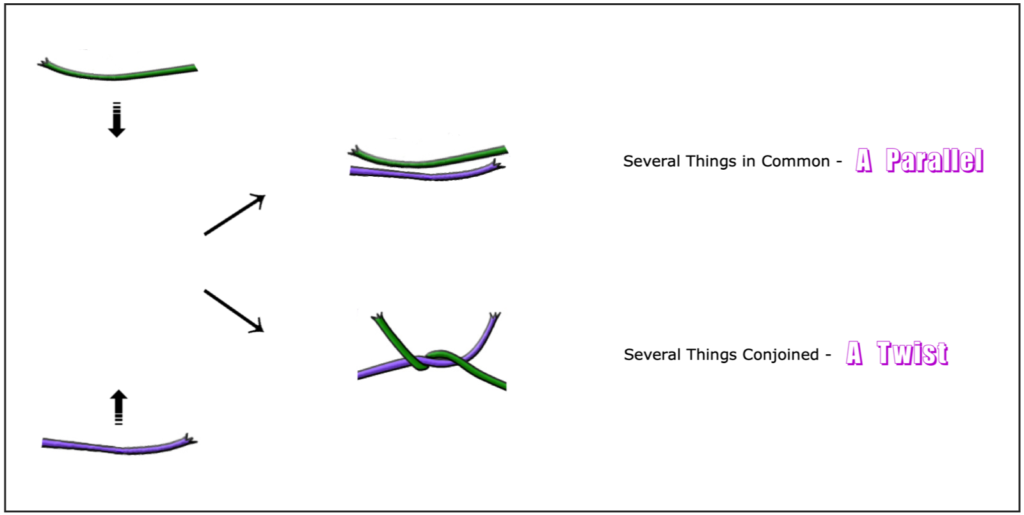

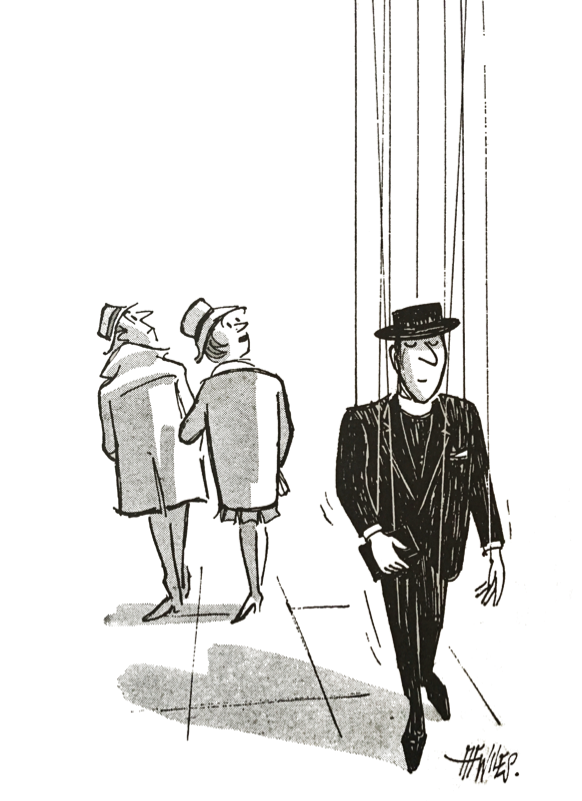

Meanwhile, we can put this simple model into graphic form. We can do this by using the idea of ‘strings of meaning’ that Koestler used with such effect in his splendidly well written ‘The Act of Creation’. Where he defined the pun as ‘two strings of meaning tied together in an acoustic knot’. A book that attempts (and sadly fails) to crack the special code underlying the joke idea, but that inspired me into thinking more about jokes and how they work.

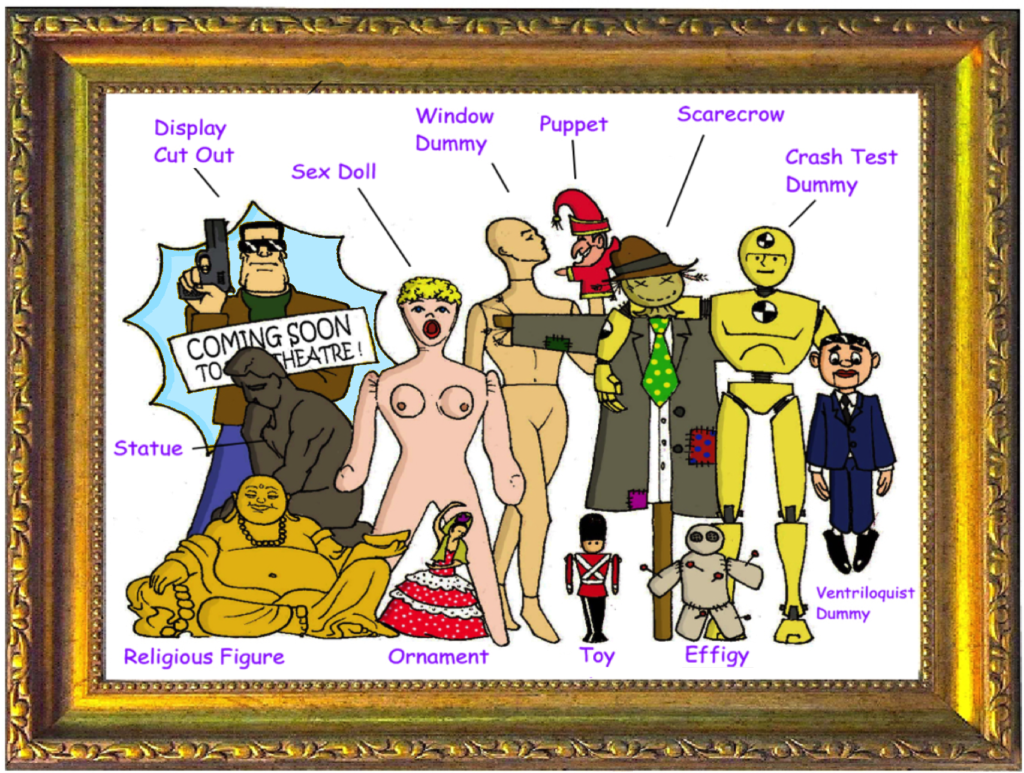

What does our emerging understanding of the joke dynamics tell us about the Copy Plateau? Well, by twisting its contours, we are learning about the underlying logic of the relationship between an original and its copy. For example, we have already covered the principles of copying fidelity, the primacy of the original, and copy advantage through the agency of just one cartoon. And as we proceed, we will find that a rich population of copies inhabits this plateau, ranging from fake body parts, such as wigs, nails and prosthetic limbs, to toys, statues, paintings, theatre props, puppets, panto costumes, maps, moulds, fake money, military targets, blanks and decoys.

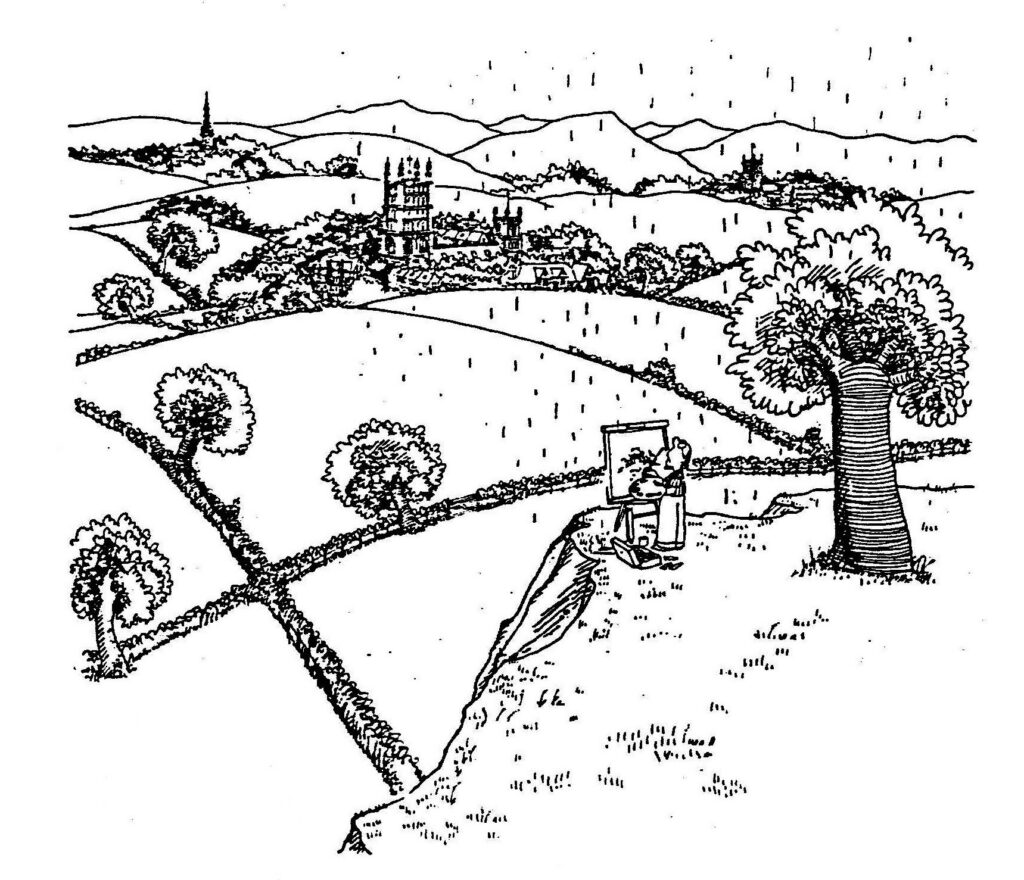

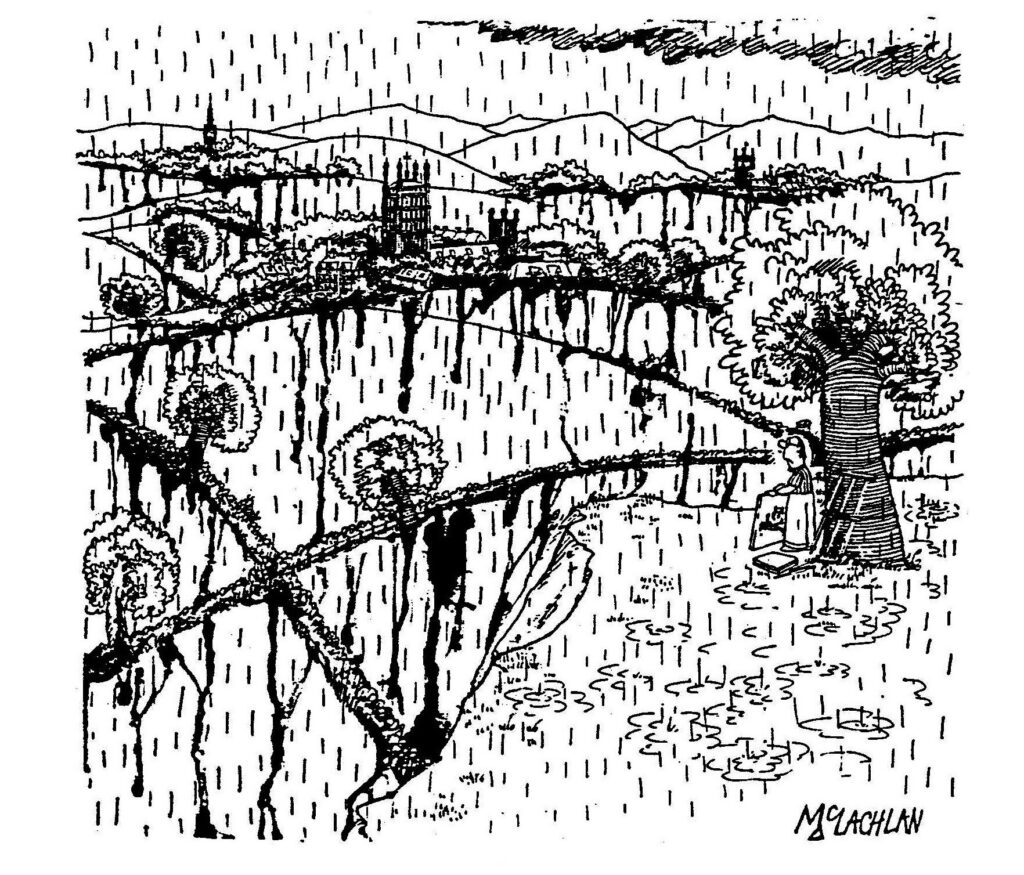

Not all copies are three dimensional. Maps and Pictures are two dimensional, and it is their renunciation of that third dimension that is often a major feature of their copy advantage. Though in the next cartoon, the twist is not about the copy advantage of two dimensions so much as about the asymmetry between the original and its copy, where the original always has primacy over its physically contrived representation (because it always comes first).

This second cartoon is simple and effective in its visual message. We see a landscape that is behaving like a watercolour painting with respect to just one property. It runs in the rain. So again we are looking at an example of an Original/Copy twist, but this time, the imitation runs in the reverse direction, because it is the original that is behaving strangely, in this case by imitating its copy.

Watercolours run in the rain, and the landscape has taken on this gratuitous property of its copy. The result is visually dramatic. It is also radical. Because this is a twist that goes totally against the primacy of the Original – a basic principle of the Original/Copy relationship.

The fact is that copies only exist by way of a direct reference to the original they represent and imitate. That is their existential baseline and their sole source of meaning. Copies imitate their originals – by definition. But the opposite is not the case: the original is not defined by its copy. Indeed it stands alone, entirely without reference to the copies that may surround it. Which means that if we go against this norm by causing the original to imitate its copy, then the result is likely to be striking. And if the twist is radical, we need a good legit to make it plausible. So, the question is, how does the cartoonist help us to accept this landscape running in the rain?

Well, the visual authority of the second frame stops any questions dead before they even have a chance to arise. The picture before us is so convincing that any added explanations or arguments are completely beside the point. In fact, the visual reality of the cartoon is almost as good as the best legit there is – which is reality itself. Though if we were looking at a real landscape, and the rain made it run, our reaction might not be laughter. And in that case, the ‘twist’ would certainly need a serious explanation, rather than a playful legit.

Notice that in practical terms, the cartoonist has simply capitalised on the fact that his own drawings are themselves ink copies, and this ink can therefore be made to run in a highly convincing manner. But there are other aspects of the cartoonist craft that we can also appreciate if we look more closely.

For example, imagine this cartoon as just one frame, with the artist and his easel absent, but with the landscape running in the rain, and that’s it. Would it work? No, this would be unsatisfactory because we would immediately wonder why the picture is running. However, by putting the artist and particularly his painting back into the scene, we are reminded of the relationship that is being twisted here. The copy runs, so why not the original? And this reminder is usually vital in this kind of twist due to the asymmetry between the original and its copy in the first place. Copies evoke originals, but originals do not evoke copies. So an original on its own gives no hint of the fact that a copy is involved in this joke idea (whereas in the reverse imitation twist with the wig, the copy immediately invokes thoughts of the original hair, and its properties).

Fortunately for the cartoonist, it is easy to plausibly insert an artist and painting into this scene of a landscape. But many joke ideas die stillborn because something critical just doesn’t fit in plausibly. For example, if we imagine the painter as portrait artist in a studio facing his subject, and the face of the subject is running in the rain, well we have to stop there, as the rain does not fit into this interior scene at all. So any idea that the subject can take on this notable property of the watercolour stops there. But take the idea outside by turning the art into a landscape painting and it works fine. Though note we have to put the artist into the scene as well, because hanging a picture on a tree or wall will not do the trick – that would just look artificial and gratuitous. Whereas with the artist in action at the easel, the whole scene looks perfectly normal.

Now add the two-frame format, and the twist works even better. Because it advances a proper development of the twist by showing the ‘before and after’ that spells out the causal sequence. This enables the cartoonist to cleverly remind us of the particular property of the copy that is to be imposed on the original – the watercolour artist is seen to take shelter from the impending rain to protect his painting from damage – leaving us in no doubt as to the property at issue here. In addition, by using two frames, the artist can create a really dramatic contrast between the normal scene, and its extreme result in frame two. A big plus in terms of its visual presentation then.

So MacLachlan has solved the problems of property reference, physical fit and causal link by inserting an actual copy, along with artist, and using a two-frame format. Along, that is, with managing the graphic challenge, where getting just the right amount of running ink was surely a good test of his patience and draughtsmanship.

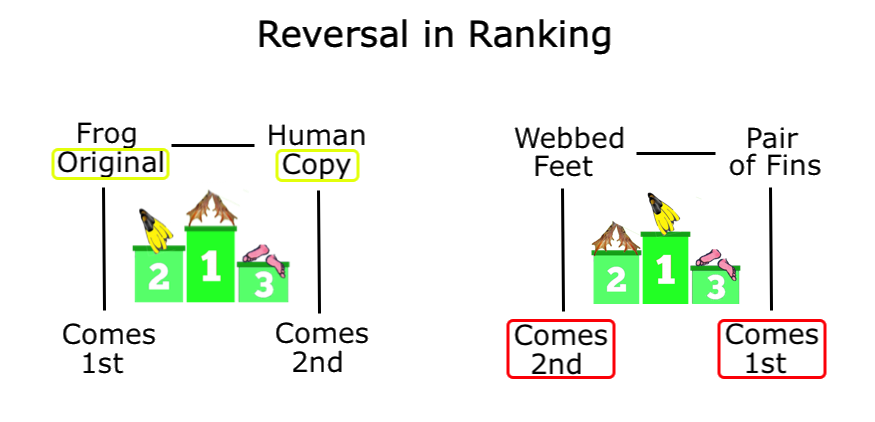

What if we compare the Wig and Running Landscape cartoons to each other? Well, in the wig cartoon we have a caption, and the context is social, with the logic of the twist inserted into the world of retail sales, involving both a salesperson and a customer. But things are very different in the landscape cartoon. Here the scene depicts an attack on the physical world, with no caption because no social scene is involved in what is effectively a pure twist on physical property and appearance. So the main difference between these cartoons lies in the direction of the two twists. Because although the wig cartoon pushes further in the direction of increased imitation, the landscape cartoon defies this normal direction of imitation, and forces the original to imitate its copy. Making the original like copy twist the more radical of the two.

To repeat, for an original to imitate its copy is more radical than the reverse – because copies already imitate their original, so the move to greater levels of imitation is not a big step. In fact, maybe we should talk about the ‘Copy MORE like its Original’ twist because that way, the asymmetry is explicit, given that the other member of the pair is simply ‘Original like Copy’. We can also express this asymmetry in another way:

Reversal is more Radical than Exaggeration because it points in the Opposite Direction.

It is only when the ‘Copy more like its Original’ twist is pushed so far that it actually starts imitating the negative properties by virtue of which it exists in the first place, as in our extreme example of the wig cartoon, that we see a twist as radical as the ‘Original like Copy’ twist. But it is interesting that we can compare the abstract quality of twists by looking at their direction like this. Perhaps we will be able to make some seriously objective points about how we can evaluate the differential quality of jokes as this walk proceeds.

Before we look at our next cartoon way marker, we should ask what more we have learnt. To start with, having now begun to understand the language of humour, we are in a position to use it to map the underlying meaning of our human landscape of the imagination. In this case, we are charting the logic and natural history of the Original/Copy relationship. True, we have only looked at two examples, but a pattern is already starting to emerge here. So what in particular can we say about this copy plateau in relation to the real world about us? For example, what might be the favourite subject of this copy culture that we have created?

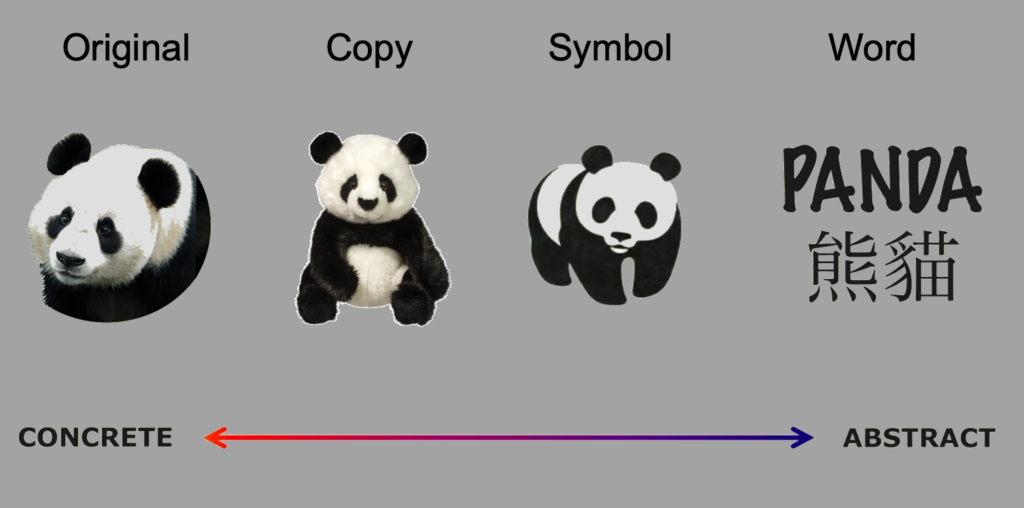

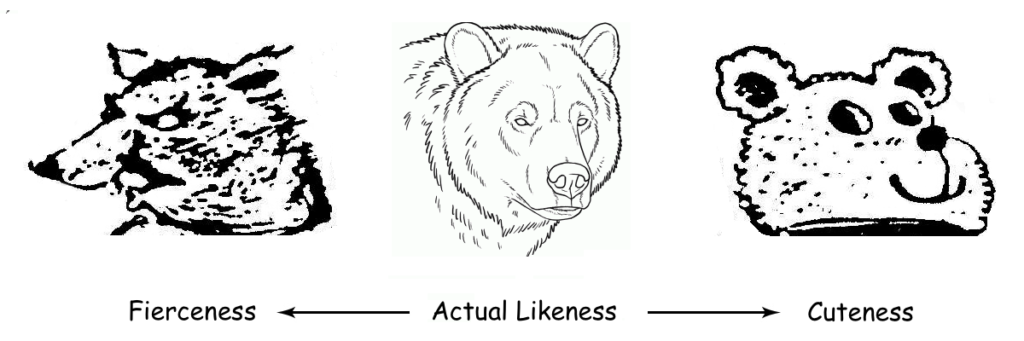

We might call this choice of favourite subject the selfie culture of copy, so pervasive is this choice and range of copy forms. But our culture is rich in many other forms of copy, because copies offer us an advantage in many different ways. For example, they may be safer, last longer, be larger than life, or for that matter smaller, be used to deceive, act as stand-ins, or allow us to reinterpret reality. So we create paintings, sculpture, toys, models, fakes and other duplicates as a stand in for things that we may want to capture, interpret, play with, understand, misrepresent or celebrate. So copies are used in every aspect of modern-day life, from teaching and science to children’s toys, retail, defence, religion, medicine and entertainment. In turn, this provides humour with a rich natural history of examples to play with, a few of which we are looking at today. But where does this Original/Copy relationship belong in the greater scheme of things? Well, if we look at the image of the wild panda below, we can see that the copy is part of the family of representational systems that includes the symbol and the word. So this gives us an idea of how important the copy is – it is how we represent the world in a materially tangible way.

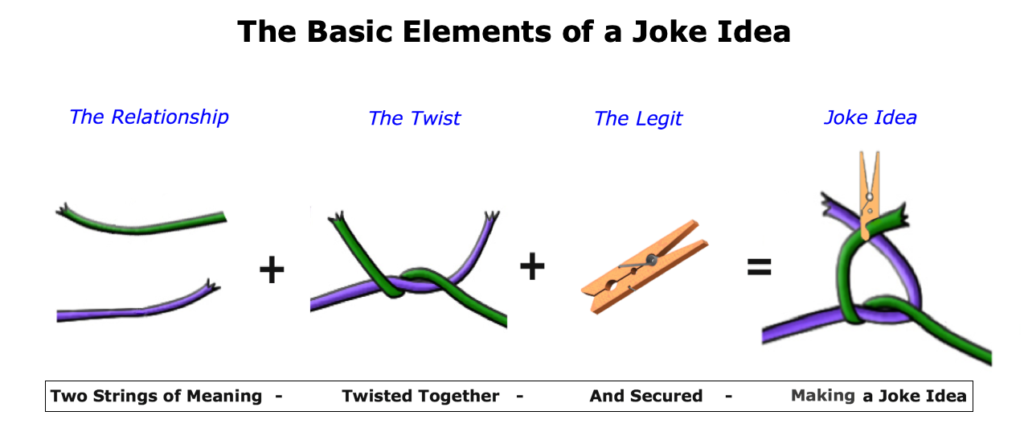

By now, it must be clear that just knowing what a joke consists of (a twist on a relationship secured by a legit) is not enough to see how a joke idea works. This is because both the twist and legit are totally dependent on the identity and logic of the particular relationship they are playing with. It is only by explaining the logic of this relationship that the twist and legit can be understood at all. But once we succeed in our understanding of the relationship in question, we get to see both sides, because the twist helps us to identify the terrain underfoot, and knowing the terrain helps us to understand how the jester creates the jokes in the first place.

Or, in terms of our walk, we can only know the terrain by where the jester puts his feet, and we can only know the jester by watching how those steps are made. That is, we get to see the landscape around us through the eyes of the jester, and in turn, that landscape tells us

about how the jokes lead to a greater understanding of the relationships that make up the landscape of meaning inside our heads, and our understanding of the logic that underlies these relationships leads us to a much greater understanding of how jokes work. Great. Our choice of guide seems to be working. Now let’s take another step forward.

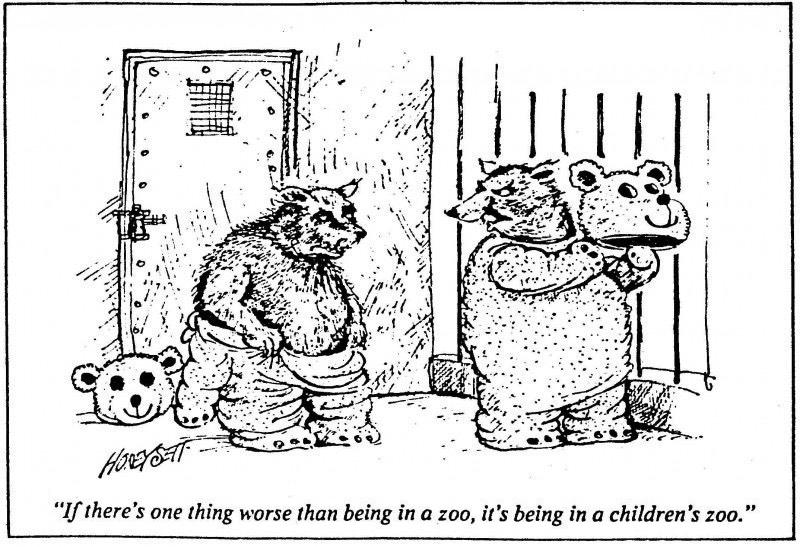

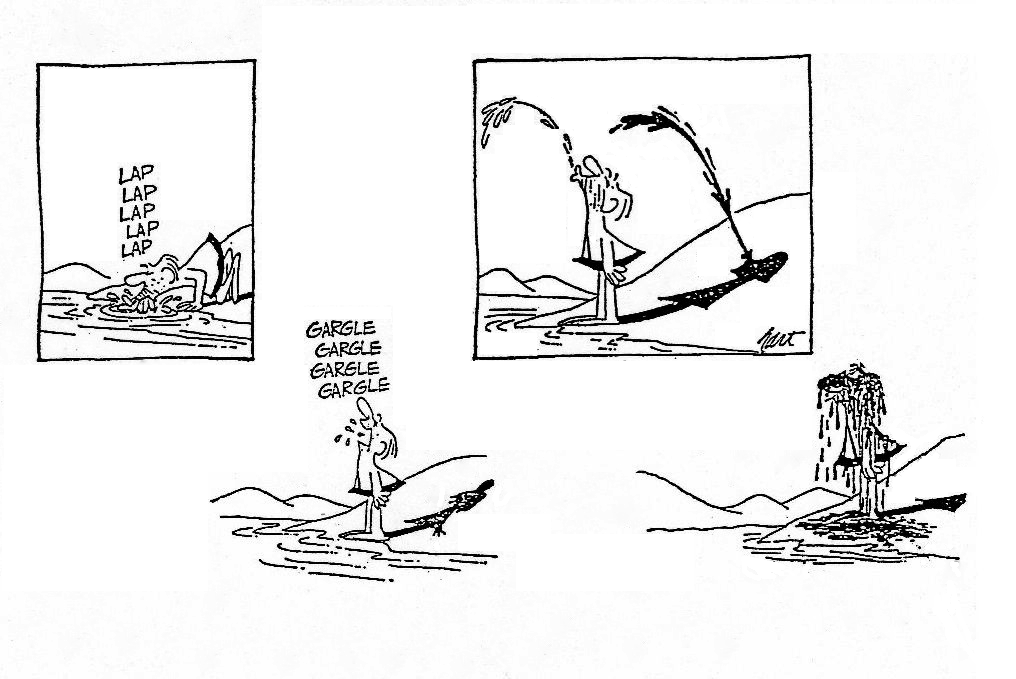

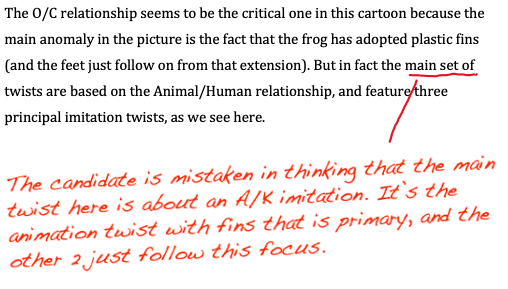

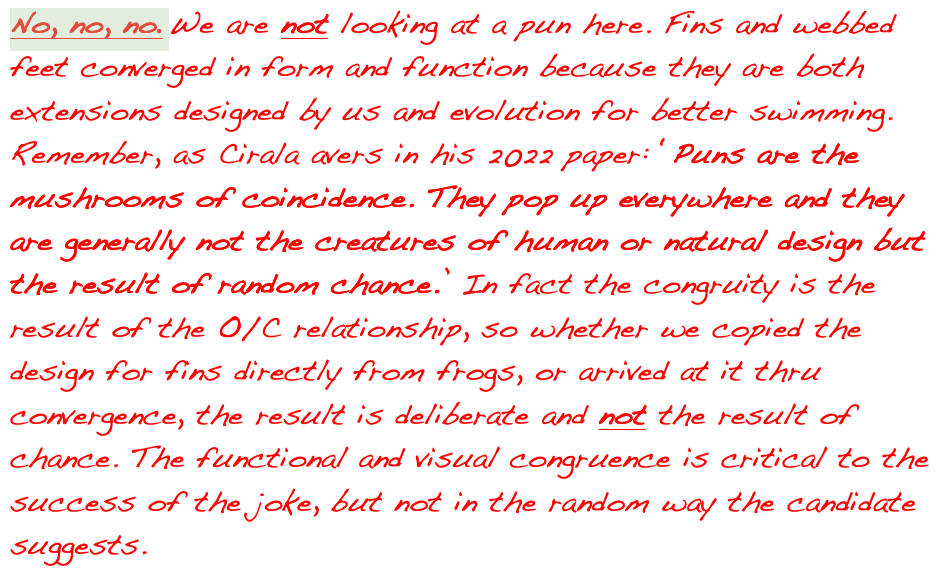

So. Here is the path that we take as we progress through this cartoon to an understanding of what in this case is quite a complicated tangle of joke ideas. A tangle of five rather different observations, all knotted together so tightly that they seem to convey just one joke idea. So let’s loosen that knot and pull out the five individual strings of meaning that make up this cartoon.

1) We start off with the bears complaining. (Imitation Twist)

2) About being relocated to a kid’s zoo. (Displacement Twist)

3) Which is using panto costumes in place of a real animal. (Replacement Twist)

4) Costumes that the bears are expected to wear and animate. (Animation Twist)

5) Because in this situation it seems that a cute copy is deemed superior to the real thing. (Status Reversal Twist)

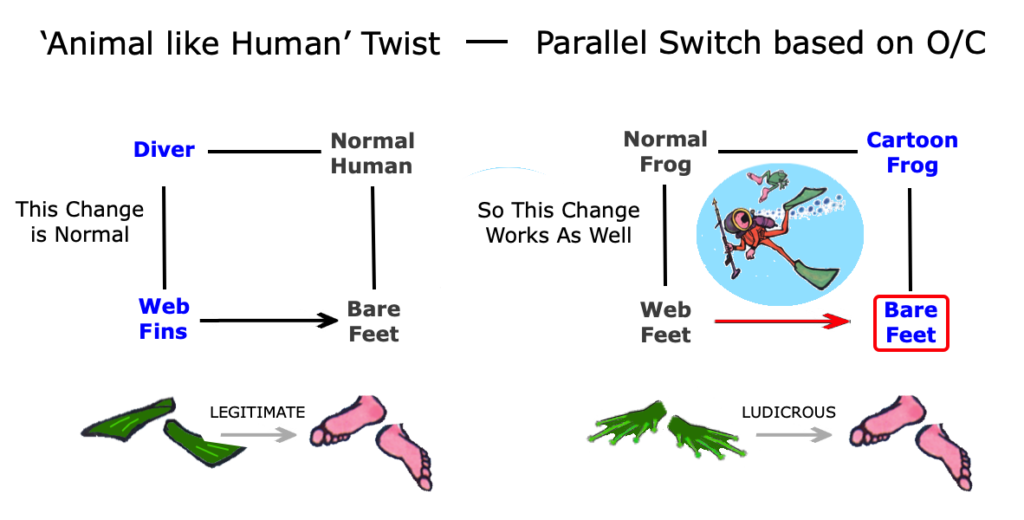

Now this list could already stand as an analysis of the cartoon, because we have teased out the various strands and seem to have successfully identified them. But we can do much better than that, armed as we are with our knowledge of the O/C relationship. Though a few additions to that understanding are necessary as we will see. Right, here we go again, but this time noting both the twist logic, and the backup that supports its apparent legitimacy (the latter being italicised). Also note that the first two twists are not about the O/C relationship, unlike the three that follow them.

1 – Imitation Twist – where Animals Act like Humans. The bears are complaining, and what could be more human than that? What’s more, their cause is just, given the indignity of their role as mere animators inside a silly Disney-fied suit that is a travesty of their real nature. It is certainly helpful that bears closely resemble us in some ways, but our human capacity to look at animals as intelligent beings is so deep seated that this close resemblance is merely icing on the cake. Clearly this twist, where animals act like humans is commonplace in the landscape of the human imagination, so it is not a radical one, and often needs no legit.

2 – Displacement Twist – An Object from one Context is relocated to Another. Real wild bears from a zoo have been displaced to a related but socially inappropriate context, where they are likely to upset or even attack the human children. What could justify such a dangerous transfer, and who is to blame? Well, at least it is still a zoo of sorts, but as far as the bears are concerned, it’s those stupid humans, who have obviously pushed things way too far (several legits there then).

3 – Replacement Twist – An Original/Copy Switch, where the Copy replaces the Original. Animal costumes belong in the theatre, or at a fancy-dress party, where they are often a source of humour. So why in this case has a Panto suit of a bear replaced the furry live animal that the kids can stroke? Well (and this is a good legit for the replacement twist), it all makes sense because the original is obviously too wild and ferocious to belong in a children’s zoo, and anyway the panto bear is so cute…

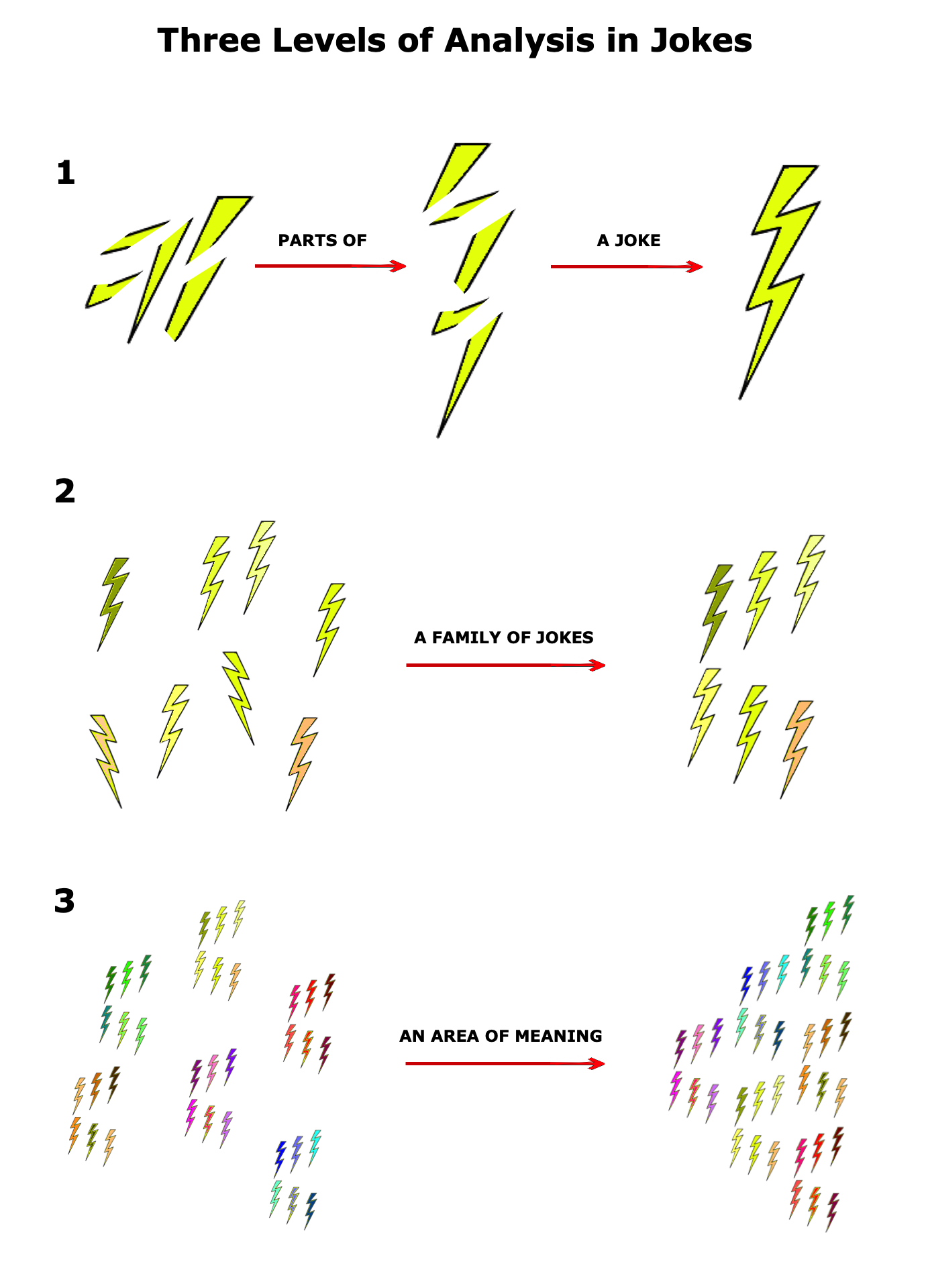

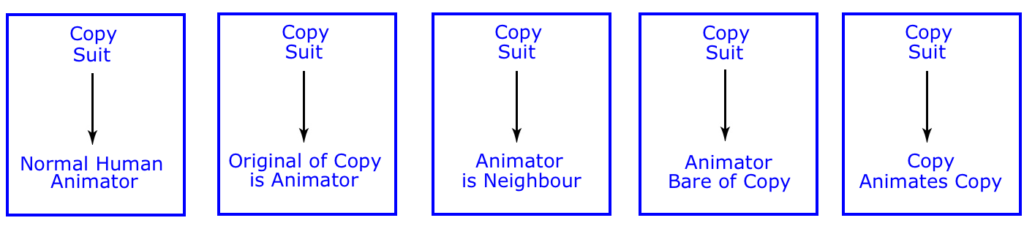

4 – Animation Twist – An Original/Copy Animator Switch, where the normal human animator is changed for the original of the copy. Which in practice means that the bears end up animating their own bear suits. An impossible and undesirable result, but in this special case, it is necessary, given the need to solve the problem arising from the displacement of the bears from the real zoo. A move we are free to question, but the bears are already there (visual authority legit again), and anyway who cares that much, as the whole idea is rather entertaining.

5 – Status Reversal Twist – An Original/Copy Evaluation Switch, where the normally secondary status of the copy is elevated above its original. On what grounds do we judge the cute panto copy as better than the real thing? Well, the context of the children’s zoo makes the presence of real bears totally unacceptable, especially given the way the artist has depicted their ferocity, whilst the Disney-fied bears are clearly perfect for the little darlings on their visit to their own special zoo.

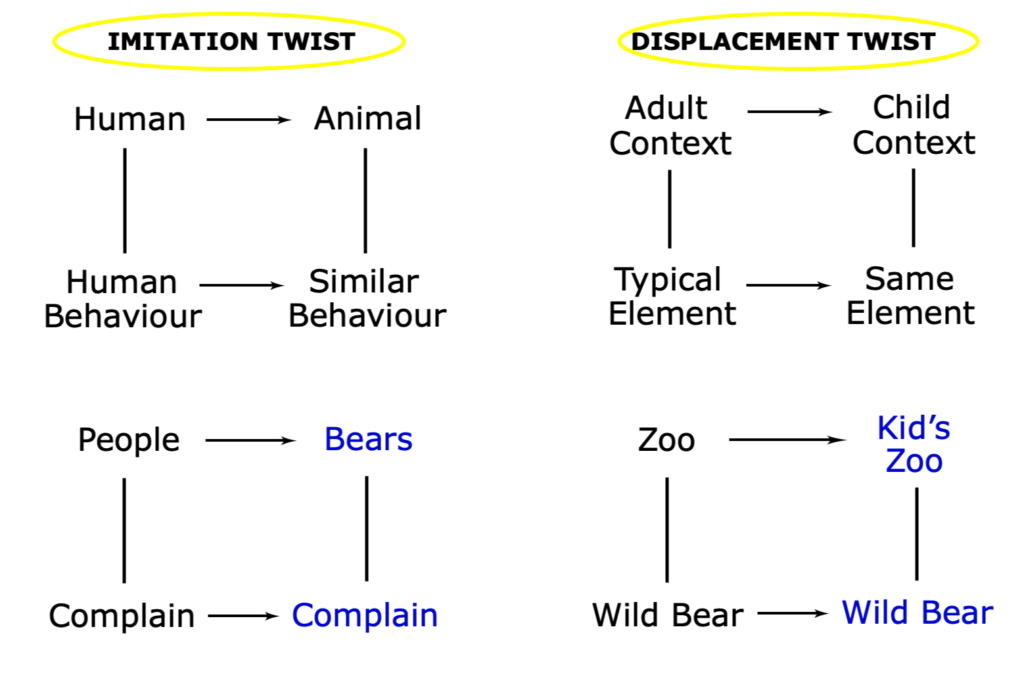

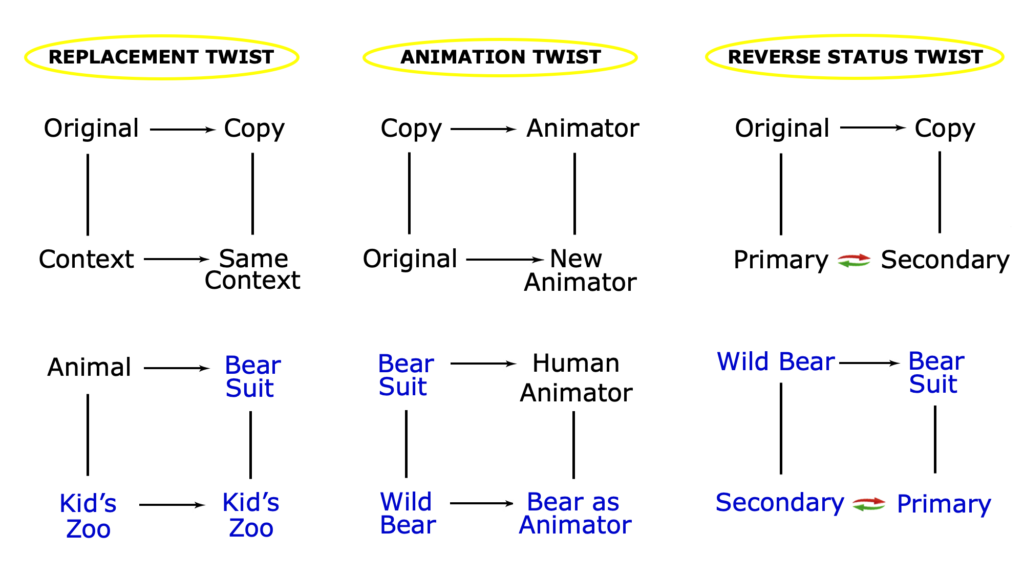

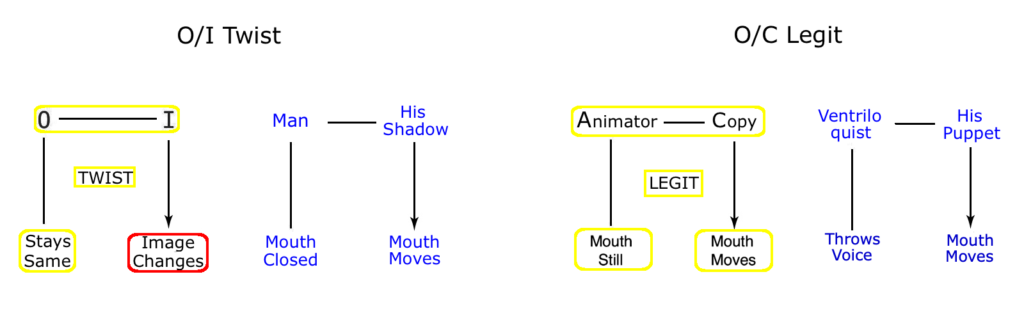

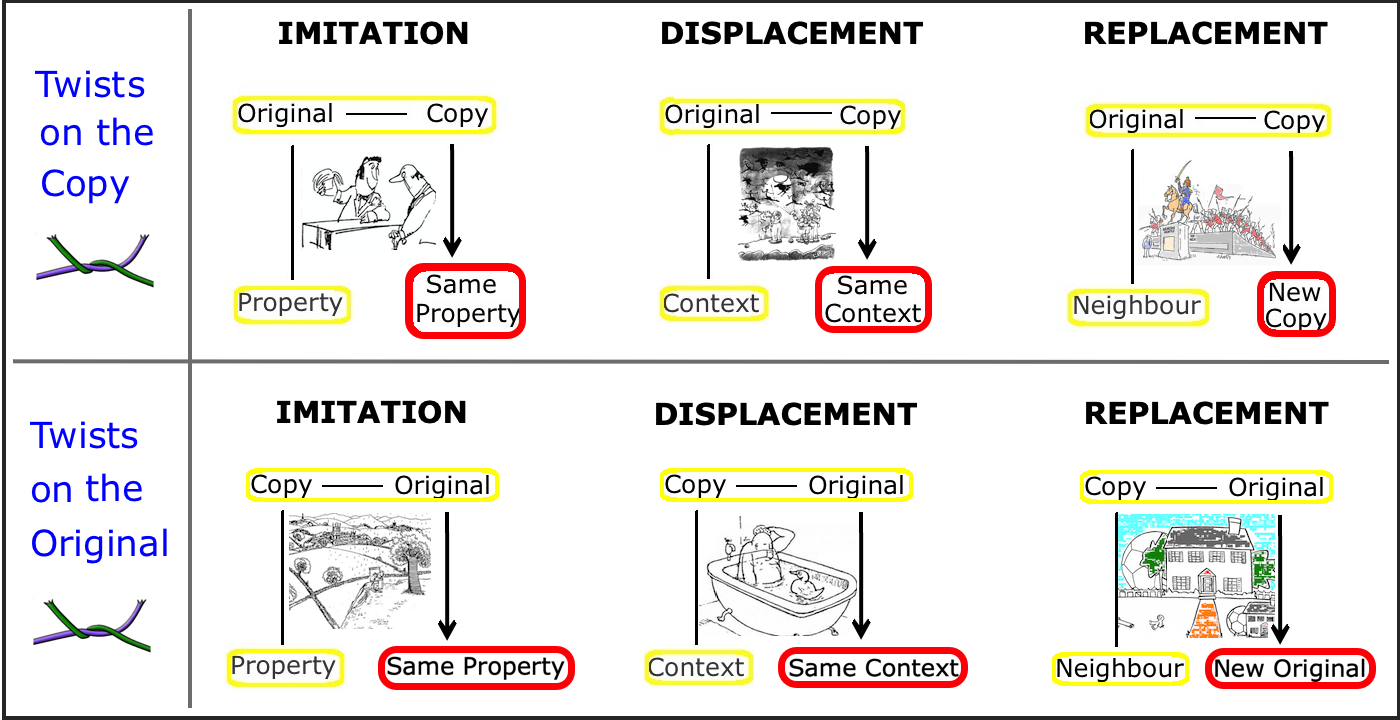

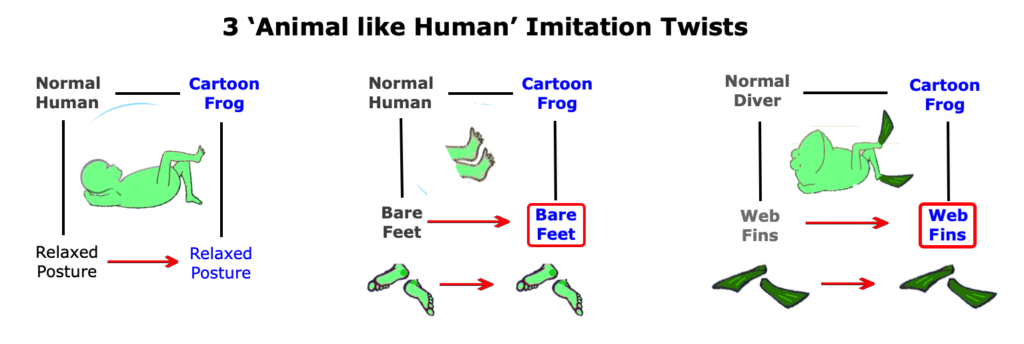

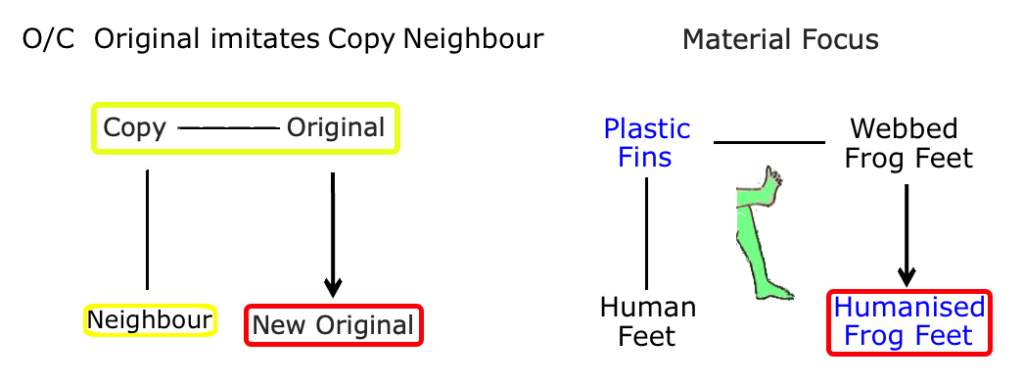

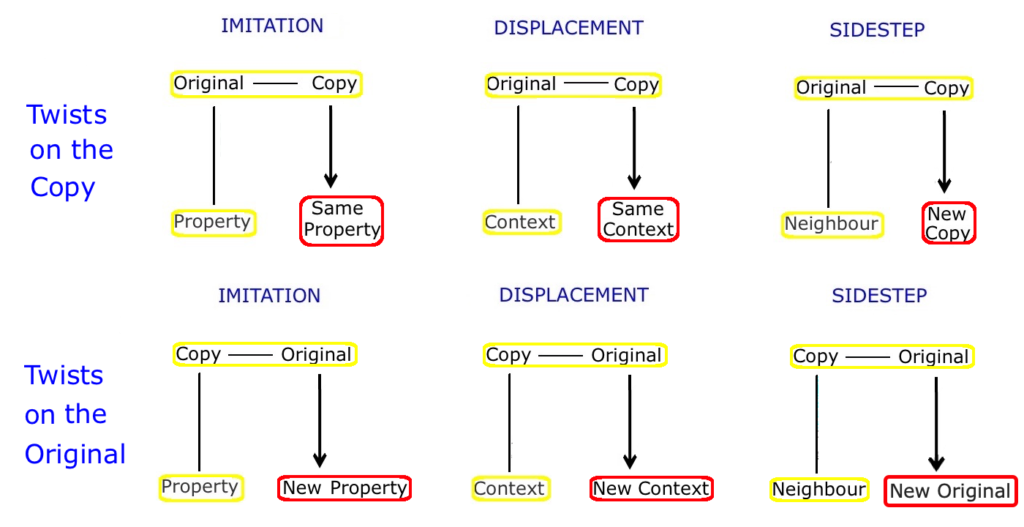

Here then is a synopsis of the twist complex in the form of diagrams. Notice that the first two twists are based on a pair of relationships that we are all very familiar with. The first plays with the Human/Animal connection, and the second with the Adult/Child relationship. It can be amusing when adults and children behave like each other, and the same applies to people and animals. However, the other three twists are based on the Original/Copy relationship.

These first two examples focus on the Animal/Human and Adult/Child relationships, these being recurrent areas of attack in humour generally. The next three work on the Original/Copy relationship, and one of these, the Animation twist, is a second order twist on O/C. Meaning that it only applies to that much more restricted number of copy examples that we choose to animate with our bodies, part of our bodies, or with machines (such as puppets, theatre props, pantomime horses, Disneyland characters and the copy figures used in advertising and publicity).

Clearly this Bear cartoon is a great example of the power of the cartoonist as both artist and humorist. The range of twists and legits fit perfectly together, and the content of this cartoon is hugely facilitated by its successful visual presentation. To wit, Honeysett’s two visual exaggerations of a real bear in the same picture, one pushing out towards total ferocity, and the other towards total docility and cuteness, is masterly.

The extreme visual contrast neatly underlines the ridiculous nature of the logic proposed in this cartoon. It captures what the caption does not: not only the extremes to which we are happy to go in representing the natural reality of a real bear; but also that we can do this in two different directions at once without turning a hair.

The enjoyable resonance of this joke is that it reveals the ludicrous lengths that we go to in order to protect our children, whilst ignoring the plight of the animals that we are so happy to exploit to that end. But here (for once), the bears are given free voice to ridicule this human stupidity, and because of the extremity of the situation, their point is made with full force. So we laugh at ourselves, but at the same time, we see the truth underlying our hubris.

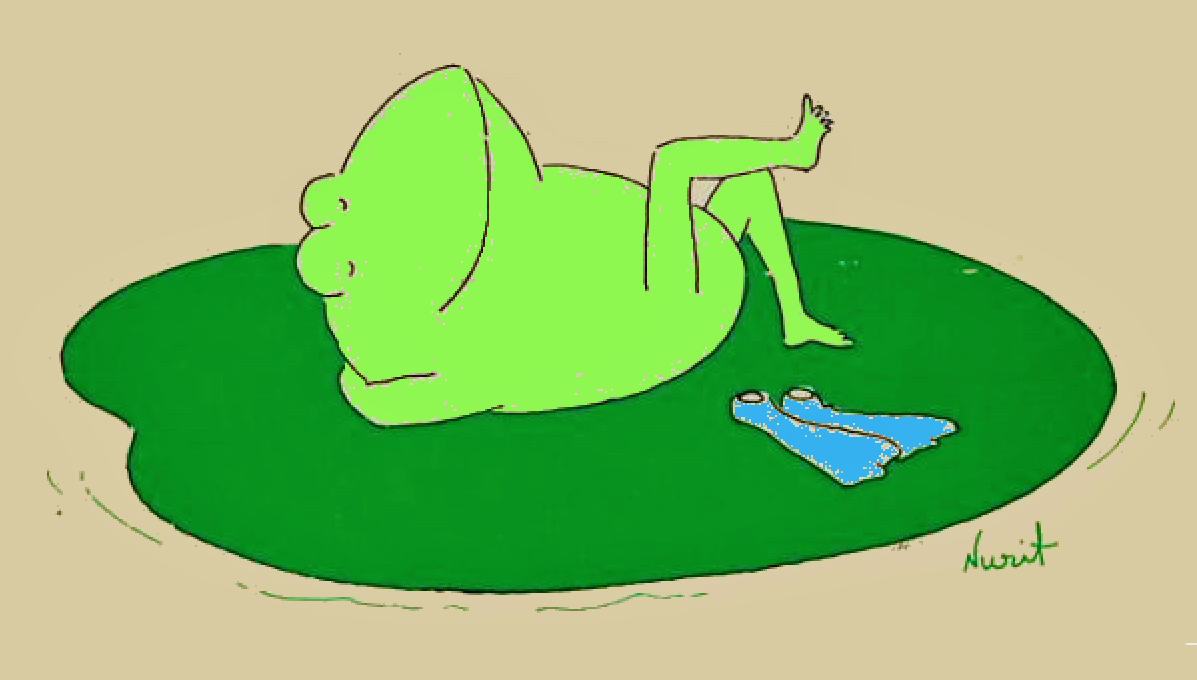

No time to dawdle, for in our next cartoon, we come across a very different kind of double act. No longer are we looking at the logic of an original and its copy. Instead, we are looking at a very different kind of double, and one created by a force forever outside the world of meaning. Sustained indeed by the immutable laws of physics, and in particular by the fall of light on certain surfaces. In short, this double act features two universally recognised kinds of physical phenomena that might collectively be referred to as ‘Images’. Which means that our walk has taken us beyond the copy plateau, and into the valley of shadows and reflections.

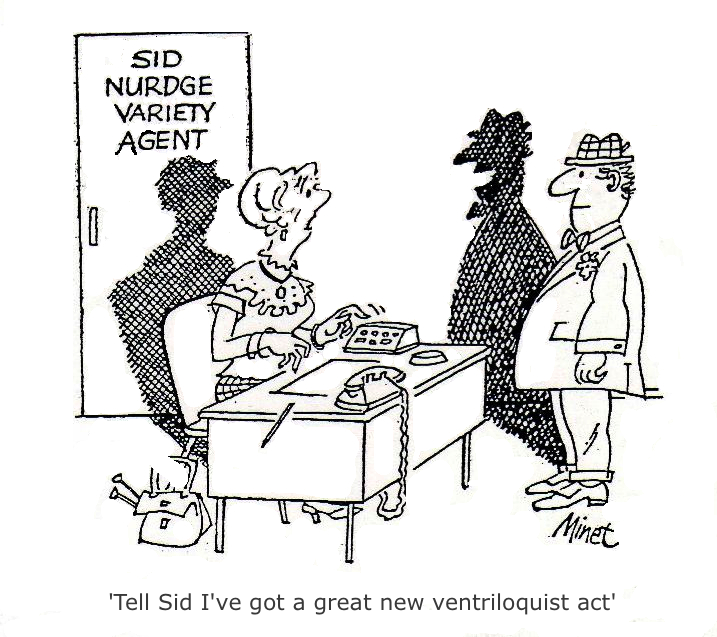

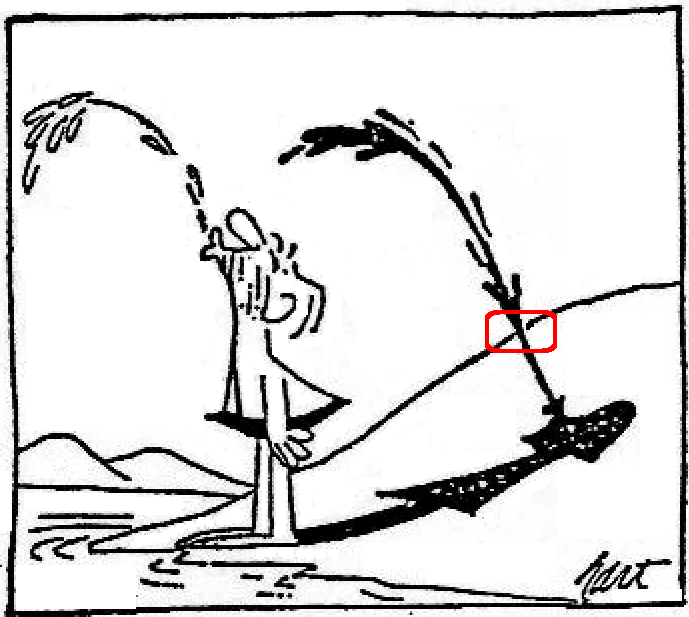

There is usually a short delay in the ‘getting’ of this particular cartoon, perhaps because it looks as if the man is listening to something the receptionist is saying. But we know to look further, as we know how a joke usually presents us with a bit of a test; a puzzle we have to ‘get’. (It is an unusual test however, because if we don’t get the joke, it’s the test that fails, and not us, as the burden of responsibility is on the humorist to ensure we resolve it quickly – although not instantly because it can also be too easy to get, so a balance between instantaneity and total perplexity is best). So we look further into the scene before us and ask ourselves two questions that address the search for both the twist, and then the legit.

- What is odd in this picture? Ah, yes, the shadow mouth is moving despite its casting object being still. That’s the twist.

- So what gives the shadow the license to do that? Ah, it’s a new ventriloquist act, where the shadow has taken the place of the dummy. Got it. The shadow is acting like the dummy and moving its mouth whilst his owner stays mum. That’s the legit. Ah, Yes, and of course variety agents are always looking for something new, so that fits too.

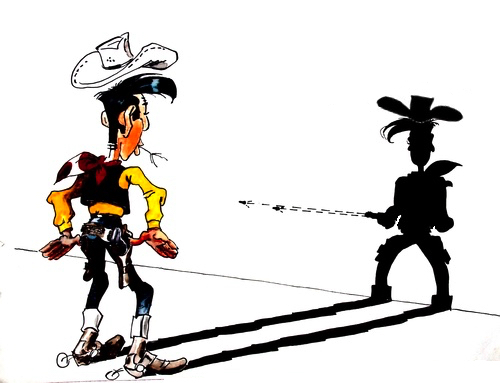

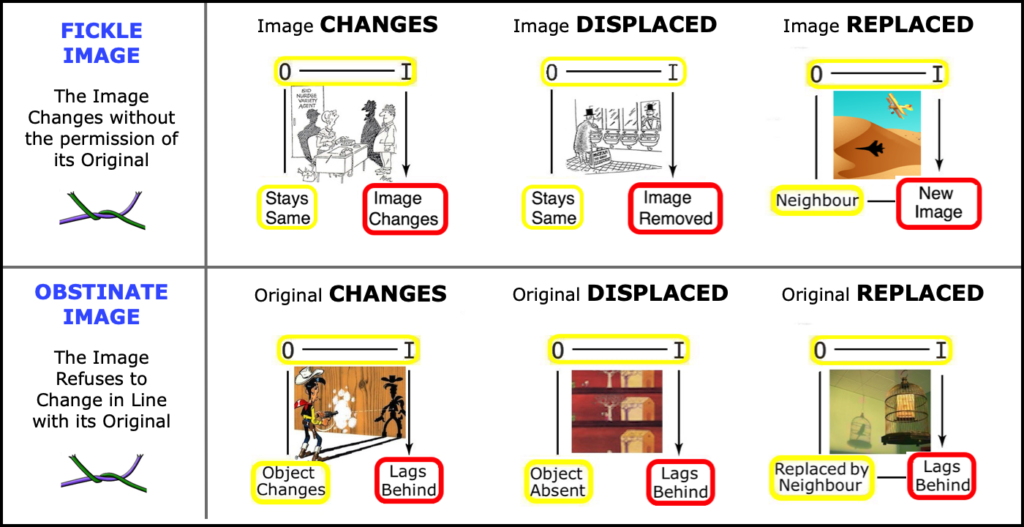

Or to put this another way, the visual correspondence between the shadow image and its casting original has been compromised, with the image changing, and no corresponding change on the part of the original. Making this is a classic twist on the Original/Image relationship (our name for the collective logic underlying the Valley of Shadows and Reflections). The images of shadows and reflections are normally faithful to their Original casting objects, but in cartoon humour, they break the faith in a number of anomalous ways. Especially in terms of their visual correspondence, as we see here.

Now, can you imagine my delight on realising that the legit can be identified with the same precision as the twist in this case? Because in this particular cartoon, the legit is based on the logic of the Original/Copy relationship, meaning that we can account for the legit to the same level of insight as we are applying to the twist. To which we might say that however hard the joke wriggles on this two-pronged fork of analysis, it is now properly secured. (Where each prong represents a relationship, one skewering the twist and one the legit).

How is this legit based on O/C logic? Well, the twist on visual correspondence is made in parallel with the idea is that the shadow can be independent of its original, because it is replacing a ventriloquist’s dummy, and the whole point of the dummy is that it can move its mouth whilst its owner does not. Once the caption has made the parallel between the image and the copy clear, we are ready to accept the twist. Despite the fact that it breaks the laws of the physical universe, where the shadow is supposed to keep pace with its casting object with the alacrity of a speed of around 300,000 kilometres per second.

Notice by the way that the O/C legit based on ventriloquism is itself a naturally occurring twist: it may be a commonplace, but a copy that moves and talks on its own is something that we all find compelling. After all, it is this very convincing semblance of an actual talking puppet that makes the ventriloquist act so entertaining. Here though, the ventriloquist act is the baseline for a very different twist, and its own identity as a twist is not relevant because we look on the ventriloquist act as a part of normal life. A norm that here offers us an excellent legit for a break in visual correspondence in the Original/Image relationship.

Note that the red boxes give the focus to the two main components of the joke: the image changes, and the link between the image and the behaviour of a particular copy provides us with an alternative and wonderfully plausible explanation for this breakdown in the laws of the physical world.

We have also noted that the cartoon gets some added support for the twist from a practice that by definition seeks novelty – namely the role of the variety agent. This is comparable to the Wig cartoon, where the search for novelty in the retail trade can also lead to extremes. Both of these examples give a plausible external reference to the ‘something new’ introduced by humour and are therefore much loved by cartoonists.

Notice too how the visual presentation in this cartoon takes care to deploy the right number of shadows. Because not everything deserves one it seems. So apart from the vital and necessarily pronounced shadow of the ‘dummy’ on the wall, the cartoonist also gives us the additional shadow of the receptionist, but that’s it. Just two shadows. The second of which is surely designed to show that the shadow situation is nevertheless normal. Because without that second (though less pronounced) shadow, the scene would look out of balance, especially given that the main shadow is so prominent. Any more shadows would distract from the main one, and probably look too busy.

At this point in our walk, we spy a good place to sit, catch our breath and admire the view, with the Copy Plateau in the near distance, and the great all-embracing entrance to the valley of shadows and reflections reaching before us. Time to reflect a little on what we have seen so far.

By now, we have seen enough cartoon examples to recognise the importance of the legit in the joke dynamics. Strange, is it not, that we can be so reluctant to accept a twist as amusing if there is no legit, but then find it funny after all, as long as we are given some kind of a spurious justification that is actually just as tendentious as the twist?

In fact this is what must have continually mystified that famous Star Trek character Spock, because this two-sided approach to reality is clearly as illogical as the jokes that reveal this human tendency in the first place. How come we are prepared to accept that fundamental and immutable physical laws can be trumped by an appeal to a trivial social act of entertainment? Such as that this shadow moving on its own makes sense because it is clearly acting as an honorary ventriloquist’s dummy? Why do we only buy the twist if it is supported by a legit that is ultimately just as spurious as the anomaly it supports? How come we take humour so seriously, by demanding that it makes sense, and then think about jokes as perfectly trivial concoctions when compared to say songs, poetry or wise sayings?

This is indeed a fact about humour that is critical to its success. The thing is, jokes are intrinsically superficial, however much artistry and sheer ingenuity it takes to create and present them. So like a flat little stone, they skim over the surface of our intellect, skipping and bouncing joyfully, to then abruptly sink out of sight. But then if we subject that flat skimming stone to undue scrutiny and scepticism, it falters, and sinks without a single bounce.

Unless, that is, we take this scrutiny to another level entirely. Hit zoom, as it were, and focus deeply into the intricacies of joke logic and its presentation at a level that goes far beyond our normal appreciation. At which point, we quickly discover that our flat little stone turns out to be a jewelled wonder of balance and meaning that makes us marvel at the creative genius that created it in the first place. For example, if we zoom in on the ‘Bear in the Children’s Zoo’ cartoon, we see just how wonderfully packed it is with colourful and intermingled flights of meaning. Flights of meaning that work together to create a complete and complex composition that should surely be considered the equal of a sonnet or a sonata in its subjective significance.

The problem here is that comparing a joke to a sonnet or sonata is difficult because, by definition, jokes are not to be taken seriously. Clearly it is time to see past this idea of the joke as a trivial entity. We must recognise that its surface shimmer of inconsequence is an important survival feature that allows it to attack the established order of things human, and not being seen as a threat. It is this ‘shimmer’ that allows us to describe the joke as a little flat stone skipping along the surface of things, making little ripples but never making waves. Because as a potential movement, humour is devoid of practical directives and has no agenda apart from making people laugh a little. Indeed its miscellaneous body of jokes can never be seen as a collective threat to the status quo because it is far too fragmented to look like a serious challenge to anything. Which means that generally, except in real extremes, it is allowed to roam free, largely unchallenged by the interests it so often attacks.

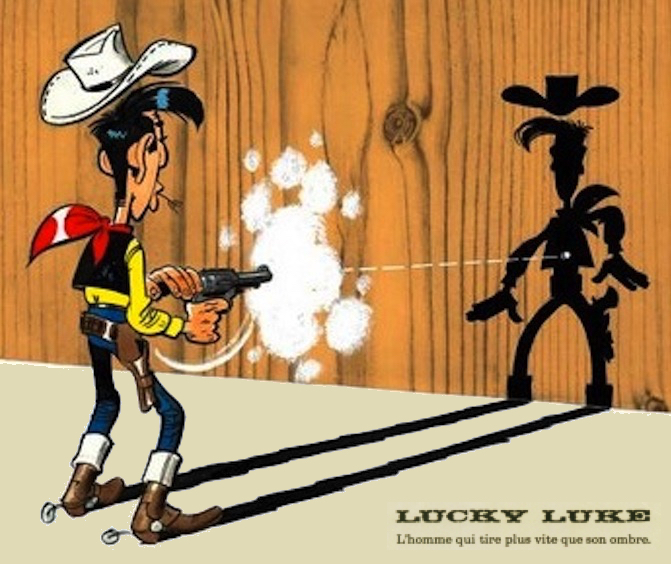

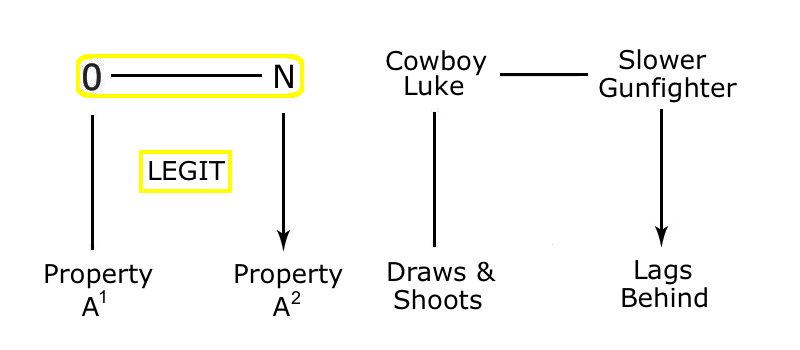

Well, we need to get on with our walk. It is good to reflect on the great landscape around us, but our next step awaits. So here is a favourite cartoon of mine. It features a cowboy hero, famous in Belgium and France, called ‘Lucky Luke’, who is not, by the way, just any old cowboy, but a super cool dude. For example, in this frame below, he is billed as the man who draws faster than his shadow.

The cartoon shows a freeze frame that reveals several fundamental anomalies in the space time continuum. The shadow ‘protagonist’ has failed to reach for his pistol in time, let alone shoot back, and there is a bullet hole in his middle. All of which goes to show that a gap in the visual correspondence between an original and its shadow may only last a second, but that this second is certainly enough to make a twist (and a kill).

Notice that the shadow is shown to be at least part way towards drawing his pistol. Indeed, if the cartoon were to show the shadow just standing there, ready to draw, the joke would be weaker somehow. So why might this be? Why is it better to show a measure of change, rather than none at all? Well, the answer seems to be that even a little change on the part of the image reminds us that shadows do follow their originals, whilst it also reminds us of the overall context of the shoot out where (and certainly in this particular case), the shadow is meant to be seen as the enemy.

Here then are the dynamics of this twist on visual correspondence.

The legit for this breakdown in VC (visual correspondence) is based on the resemblance between the opposing shadow, and a gunfighter beaten to the draw; a familiar cliche in cowboy films. Which is to say that the legit has pulled our twist into a real-life situation in order to make it appear realistic. Well, at least for the moment of the joke, and that is all that counts as far as we and the cartoonist are concerned.

This joke could actually stand on its own, in words, without a drawing. We could say: ‘Fast? Lucky Luke? He draws quicker than his shadow!’ Which works well enough. As does the cartoon on its own for that matter. However with the caption there to support the picture, there is no room for ambiguity. And together, the words and picture create a dramatic interpretation of both the twist, and its supporting legit. So a picture is not always ‘worth a thousand words’, because arguably the joke idea is carried perfectly well in just nine words in this case. Though just as clearly, the visual presentation is preferable. After all, it brings us so much nearer to the physical reality than do the relatively abstract sounds and signs of language.

It is worth asking whether this cartoon be reversed, with the shadow being faster than his original casting object? It seems possible certainly, but with less dramatic effect, because the whole idea is that a human hero is being championed in the normal version, whereas an anonymous shadow hardly qualifies as a real-life action hero. Additionally, there is an asymmetry between humans and shadows with respect to our perceptions of speed: shadows move with instantaneity, but humans do not. This makes the action of the shadow less impressive, albeit still equal in its attack on visual correspondence.

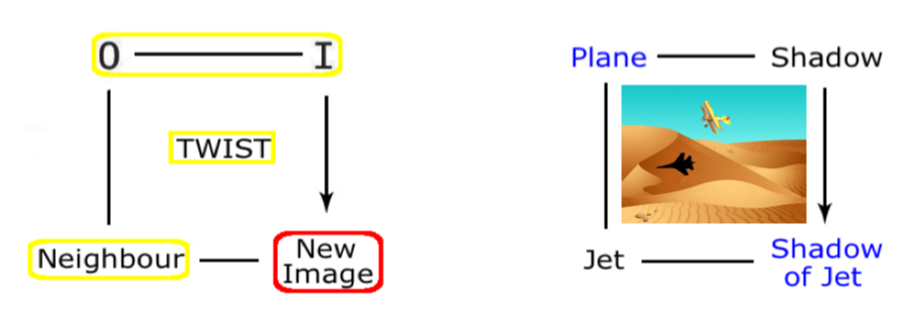

Now here is another cartoon with quite a different twist on visual correspondence.

There is no caption, so we are left to make sense of this picture on our own. However, the twist is clear: not only has the shadow changed shape, which shadows often do over undulating surfaces like a dune, but it has actually changed identity as well. So does this mean there is a jet flying way above our humble little fixed wing, casting its shadow, and it’s just that we can’t see it? But in this case why aren’t there two shadows? And then we realise what the link between the casting object and the image must be, and it all becomes clear. Our humble little plane wants to be a jet. That makes lots of sense in our human terms. Because if it was the other way round, with the real jet casting the shadow of a little plane, it would not make that kind of sense: jets do not hanker after being small fixed wing aircraft. Once again it seems, human logic trumps the logic of the physical universe (but only for the moment of the joke).

So the legit relies on us being able to imagine the plane as a conscious being, with hopes and fears and dreams just like us humans. A picture that the cartoonist can happily rely upon (and a moving entity like a plane is even easier to see as animate). Meaning that we can easily spot the unspoken logic in front of us without the need of a caption. Which in this case would surely spoil the puzzle element that so often contributes to the worth of a joke. Here then are the dynamics of this twist.

We should be clear that this kind of a twist, where the image is replaced by a neighbour of the casting object, depends on more than just the neighbour being a relative of some kind (either by property, context or some other category). For example, a shadow of a helicopter under the plane would make no sense in this respect. This is because the legit of ambition rests on a known hierarchy of speed and power in aircraft, and the helicopter steps us to one side of that obvious hierarchy. But let’s look at another version of the same joke idea.

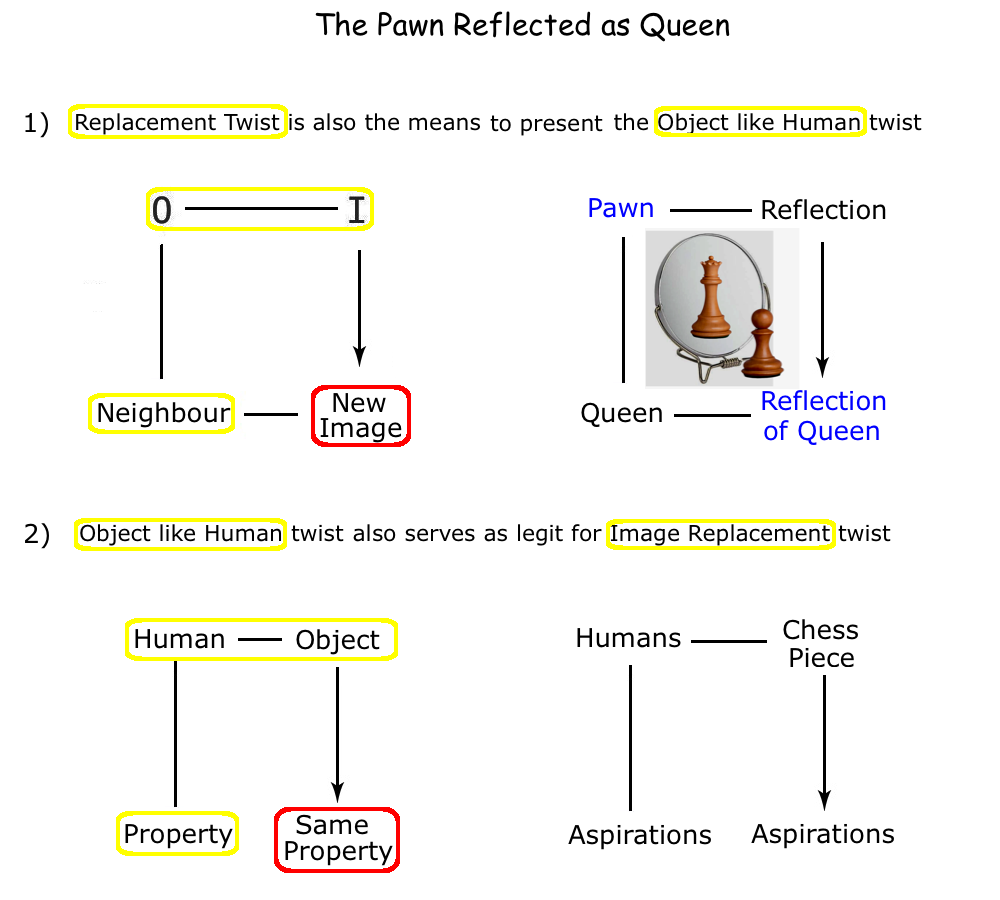

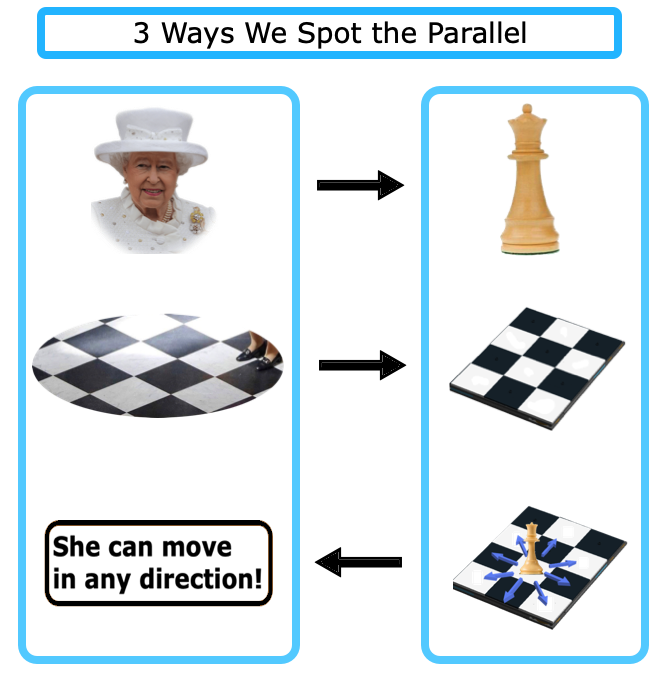

What we see here is that the pawn can dream of becoming a queen, just as the plane aspires to jethood. It is also true that a pawn can actually become a queen in the game of chess, and if people read that into the idea as a bonus, well that works too. But the question is, does the reverse work in the same way? Particularly as it is easier for us to see a chess piece (rather than a plane) as a conscious being. So whereas the idea of a jet dreaming of being a fixed wing is a non-starter, the idea of a queen seeing herself as a pawn can actually make sense to us. This is because other human situations can come to mind more easily when the figure is more human than a jet. The queen could be reflecting on how time passes for example. But even here there are limits. For example, the idea that queen is wondering about having a baby pawn is a step too far, because that stretches her status as human beyond the limits. On the other hand, very little stretch of the imagination is needed for the pawn wanting to be a queen, so the first example works the best. Generally then, we might say that for the creator of humour, treating the norms of meaning as elastic is fine as long as they are not stretched beyond the patience and understanding of the audience.

Here are the dynamics of the pawn reflected as queen. Again, we are looking at a replacement twist, with the legit based on our seeing the pawn as a conscious being with aspirations beyond their position. Just as with the ‘Plane as Jet’ example, the legit is based on an imitation twist between non animate objects and humans. But again, this perception that objects, and particularly animals, are human-like is so commonplace that it is hard to regard this as a twist most of the time.

Note that this is the same twist as the cartoon with the jet shadow, but we have switched to a reflection in this example. Such a switch from shadow to reflection is not always possible, as it all depends on the ecology of the image concerned. For example, reflections rely on the surface of a mirror or water being available, whereas the ecology of shadows is much wider than this, with shadows being utterly promiscuous in their use of pretty much any kind of surface as long as the light source is good. So shadows have an advantage insofar as they can pop up all over the place, but they also lack the filled-in details of the casting object, making the reflection a far more faithful image in that respect. We can say that shadows show property limitations (they are black), whilst reflections show context limitations (they need special reflective surfaces).

For example, we can see how the context limitations of the reflection influences the creation of this chess piece cartoon. The natural habitat of the pawn is the chess board, so how do we put this board in front of either a mirror or a flat stretch of water? Well, chess pieces generally belong indoors, so a mirror is preferable. A small frame, like we find in a shaving mirror, would give us the right scale for a small chess piece, but the bathroom is hardly a natural part of pawn ecology. We can get away with it though. How? By losing the bathroom altogether and reducing the scene to the absolute minimum. This means we are relying on the tolerance of the viewer to discrepancies in the ecology of human objects for the sake of the joke. ‘A pawn looking at itself in a shaving mirror is it? Well, okay, go on then.’

A word about the ecology of human objects. How do we humans look at a plane or a chess piece? Certainly not in terms of its mass, volume, temperature and molecular composition. We leave that to the chemist or physicist. Rather, we see these objects in terms of the multifarious reasons we made them for in the first place. So the ecology of a pawn is based on its position on a board, relative to the pattern of the other pieces, as defined by their particular and characteristic moves, all within the overall context of the game. The pawn has physical properties certainly, but we look to its style and finish, rather than to its mass and exact composition. We look to its context in the human landscape, such as a games shop, or international competition, rather than to its geo spatial location. And we look at its invisible ties with neighbouring objects, such as the queen – ties that to us seem far stronger than the real physical and gravitational ties that both chess pieces necessarily have with the planet we live upon.

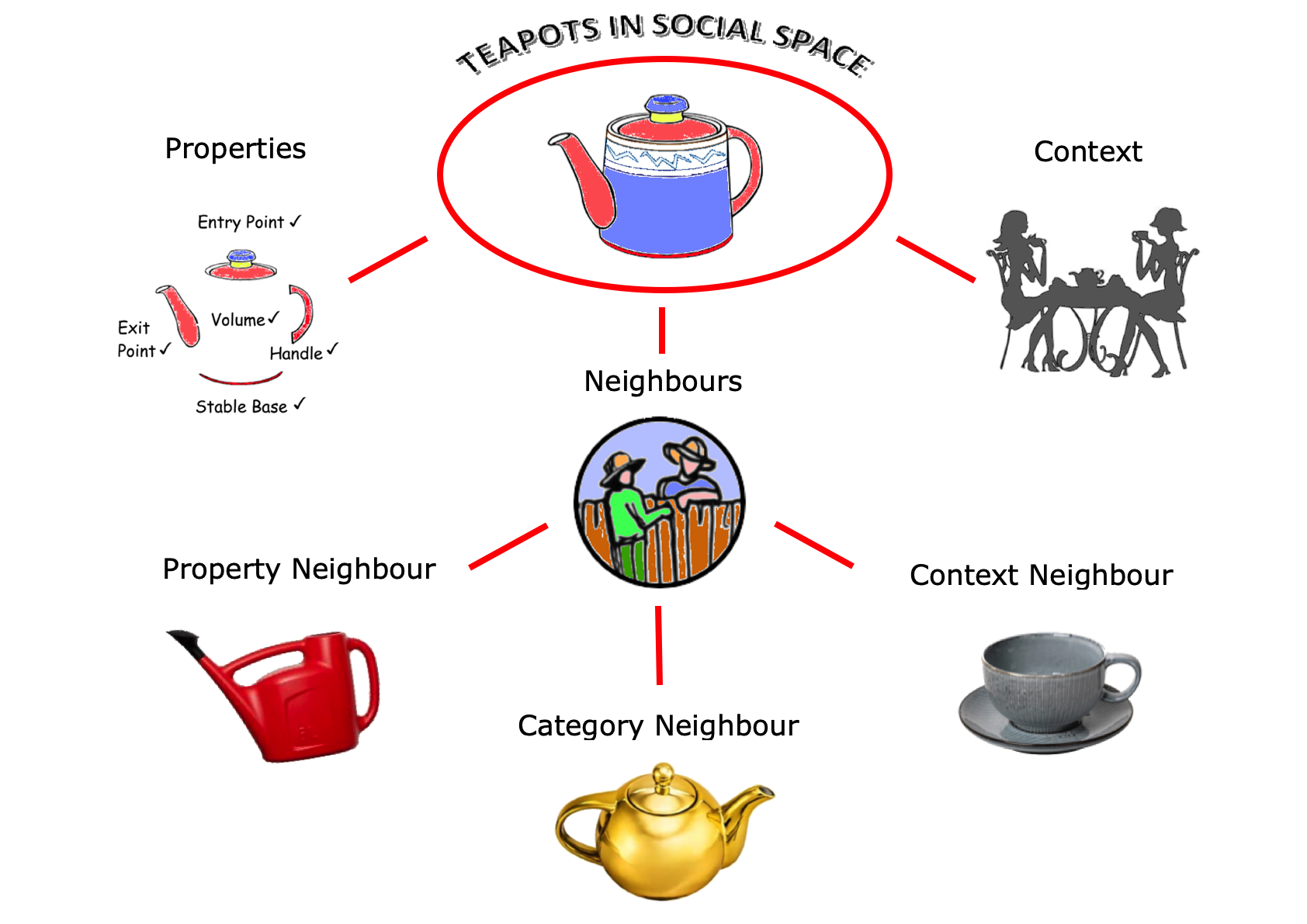

Objects in the field of gravity that is human meaning have three easily identifiable physical aspects: property, context and neighbour. For example, a wooden knight looks like a horse (property), lives on a chequered board (context), and is associated with pieces such as the rook and bishop (neighbour). A plane has wings and propeller, belongs on an airfield or aircraft carrier, and has jets and helicopters for neighbours. Now it is true that all three of these aspects are physical, and there are others that are not (eg price, history, style), but none of these aspects have much to do with the world described by the physical sciences. Simply put, their identities lie far beyond the explanatory powers of the physical and biological sciences, great though these may be.

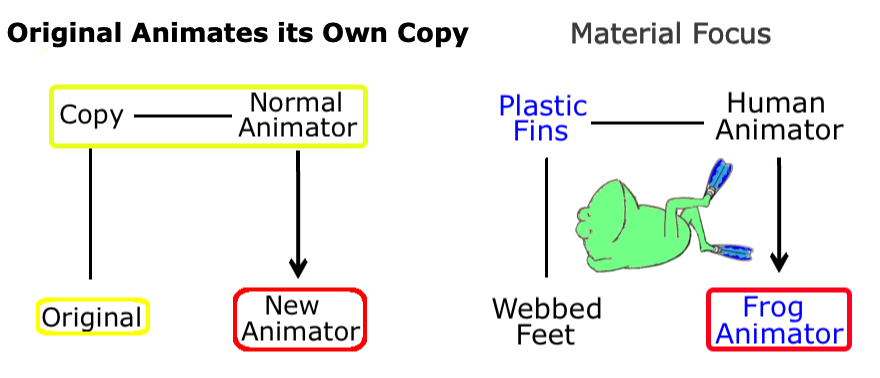

To see the power of this triple aspect of objects in Social Space (as opposed to Physical and Bio Space), we can look at a family of cartoons, two of which we are already familiar with. Notice how the twists are organised and separated according to this triplet of property/context/neighbour.

This also applies to some of the twists on the Original/Image relationship. Again we find that a key organising principle is based on the ecology of objects in Social Space.

True, in this short walk, we are only considering a few examples in each family but the general pattern is similar in a number of ways. In particular, what we see is that this same triplet is the key organising principle of this family of image twists as it is for the copy twist family. So each vertical pair is based on the property/context/neighbour triplet, making six possibilities in all. (Although both the O/C and the O/I relationships also show a number of other possible twists that are not revealed here). Notice however that the O/C family features a pair of imitation twists, whilst the O/I family, with its impressive levels of imitation, has to go the opposite way, and feature a pair of breaks in that imitation.

What is rather interesting about this triplet is that the third member, the neighbour, can then be divided into three different sub categories according to the triplet of which it is itself a part. To create Property, Context and Category neighbours to be precise. So for example a teapot has property neighbours such as the milk jug and coffee pot, context neighbours such as the sugar bowl and butter dish, and category neighbours, which are all the other kinds of teapot. As indeed we can see in the diagram below. The point being that if this triplet applies to its own members, then that suggests that this really is a valid way to understand the world of human objects, because it is recursive. Though the exact reason why that should be a point in its favour is still unclear to me. Anyway, it works, and that likely means something.

Objects in Social Space are different from objects in Physical Space. In fact 99.999% (with the 9 recurring) of the objects in the physical universe, however large, small, numerous or distant, have no meaning to us because we are entirely ignorant of their existence. On the other hand, objects in Social Space (the third level of reality on this planet after Physical and Bio Space), gain their meaning through their physical properties, their setting, and their relationship with other objects. For example, copies exist because they enjoy meaningful freedoms that their original objects do not possess. Images are different however. They exist independently of us, and although they are generally accepted and sometimes manipulated by us for purposes such as human entertainment, they do not carry the created meaning that we imbue in every single copy that we make. Instead, images are drawn into the gravitational field of human meaning when they prove useful to our purpose, although they are a major element of our background experience as well.

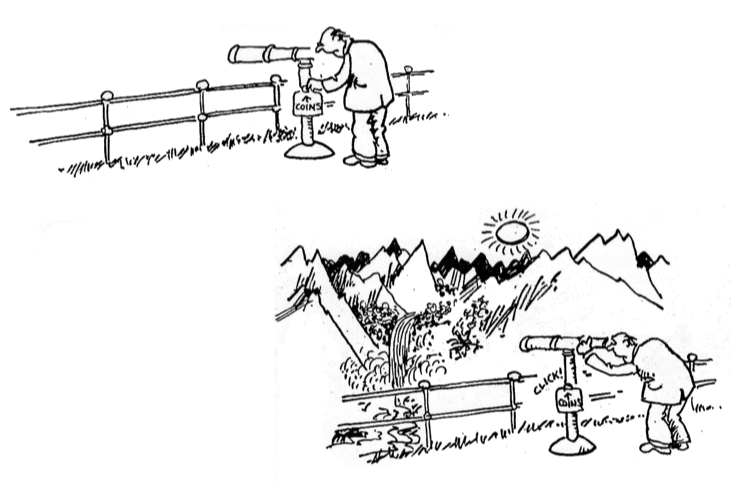

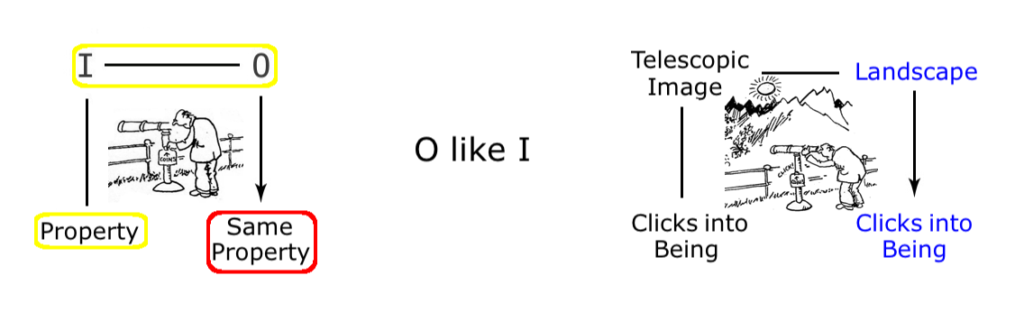

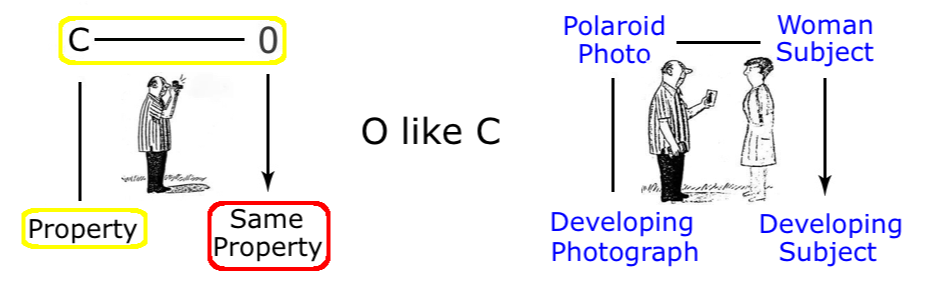

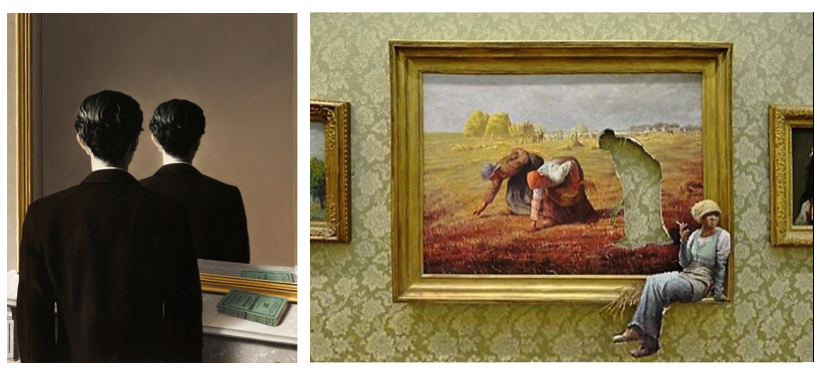

Now let’s make a comparison between two very different, and yet very similar cartoons, one playing with the Original/Image relationship; the other with the Original/Copy relationship.

Firstly, we should ask whether the telescope, which involves mirrors and lenses just like the camera, is not a copying machine as well? What is the difference? Well, we just have to look for the visual correspondence that typifies the O/I relationship. So we know that the telescopic view is an image, and not a copy, because we know that the telescope works in real time. The camera, even when it is working in real time as a video unit, is storing the view for later use, whereas the telescope just gives us a magnified reflection that constantly mirrors the reality it is pointed at. In short, images are transient, whilst copies are for keeps.

Now let’s go through the dynamics of the telescope cartoon first. We are all familiar with the idea that when the casting object is absent, the image is absent too because that is how the normal world works. But here, it is shown the other way around. Here we see that when the image is absent, the casting object is absent too. Almost as if our image maker, the telescope, is not just the way we capture the image, but also the creator of the original landscape at the same time. All with just the click of a coin.

So what we see here is that this particular landscape is behaving exactly like its coin operated image, clicking into being only when its image appears inside the viewer of the telescope. Which means that it is an original behaving like its image, only present when the coin is active, and immediately absent when the coin’s value has expired. Notice by the way how the cartoonist has been at pains to draw up as impressive a landscape as possible, in order to emphasize the switch from nothing to everything.

So this is an ‘Original like Image’ twist.

The text in blue merely indicates what is present in the actual visual presentation, whilst the text in black is implicit. The diagram shows that this cartoon uses an imitation twist, and that it is not therefore primarily a twist on visual correspondence. The original landscape is taking on an attribute of its image (in this case the view through a telescope, controlled by a coin), and that makes it an imitation twist. But then, are we not also looking at a dramatic instance of a break in visual correspondence as well? To which the answer must be that we are, and that all O/I imitation twists necessarily involve a tweak in the visual side for them to be visible at all. So how do we then argue that this cartoon is primarily an imitation twist?

A quick look at another cartoon, where the imitation twist is clearly the point of the joke can help illuminate this ambiguity. But even before we look at it, we know there is going to be a break in visual correspondence, because any change between an original and its image is bound to break the correspondence between them. However, the the main point of the joke idea in the cartoon below (featuring the cartoon strip hero BC) is that the shadow imitates two physical entities. One is a fellow human being made of an active shadow, intent on soaking his master to the skin. The other is the jet of water that does indeed soak him.

The focus of this imitation twist is in frame three (see below), where the shadow shoots into the air, to cross a critical boundary. Critical because it marks the difference between the real world outside, and the virtual world inside our heads. Yes, we know that a shadow cannot manifest visually in thin air (let alone as a spout of real water), but the join between the two realities is so neatly done, we barely notice it. Notice how the shadow spout passes this critical point exactly where the line of the hill becomes the air. Doing so in complete synchrony with its casting spout of water to its left, allowing it to then carry on as if nothing untoward had occurred. Making for a final and dramatic denouement that conceals the ‘crossing of the line’ between the two different realities of the Physical and Human worlds, where the sleight of pen that is the hand of humour is invisible for that all-important moment of the joke.

So although this cartoon features a break in visual correspondence, the main point is the way the shadow imitates its master and the world of physical reality around him. Nor is the shadow behaving in a fickle or obstinate manner, like we are used to seeing in the family of six twists on visual correspondence that we looked at earlier. For in this case it has taken on a life of its own, both by spurting water and behaving in an openly defiant way by drenching its master. Indeed, the cartoonist has cleverly used the synchronous appearance of visual correspondence all the way to the end, to fool us up until the last possible moment. Clever stuff.

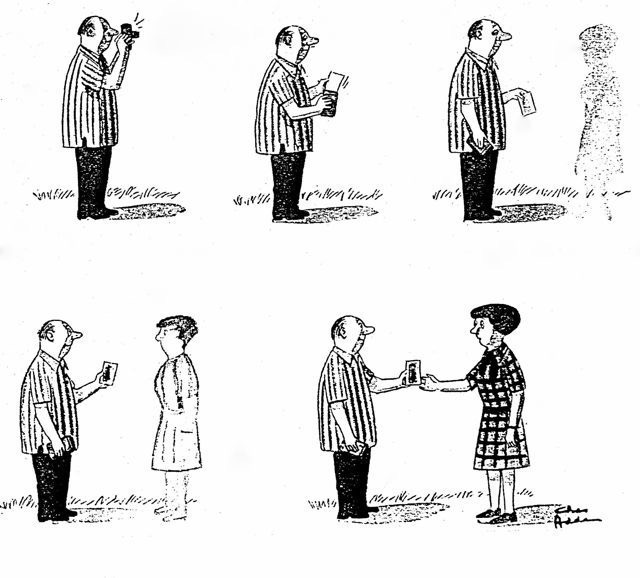

What about the polaroid cartoon then? Well, if we look at the dynamics of the twist, we see that it gives us another imitation twist, this time based on the Original/Copy relationship.

Notice how both the polaroid copy and the original subject come into being at the same pace. This makes it clear that the subject is just as much the result of the polaroid processing as the photo is. On the other hand, there is nothing gradual about the telescope ‘click into view’ image of the landscape coming into being, because there we have the speed of light to contend with. But in this cartoon, we have the speed of photo chemical reactions to deal with, and as we know, that still magical process is rather slower.

No clever legit is offered to us in either the landscape or the polaroid imitation twist, but the visual authority of the picture carries the day. Besides, we are used to the idea that telescopes and cameras are, as I suggest, slightly magical in the way they capture and remake reality, so that eases our way.

In humour, it is much easier for an image to find a property to imitate than it is for the original casting object. For example, if an image imitates a person, there are plenty of aspects to that person to choose from. But if the person imitates his or her shadow or reflection, then there is quite a small list of special image properties to choose from. This is an asymmetry due to objects being property, context and neighbour rich, whilst their images, once shorn of all their object derived characteristics, are left with rather few unique features.

Why might this be the case? Well, images only have a small set of properties unique to themselves, like distortion, position on a surface and dependence on the original and a light source. So for an original to imitate its image, the humorist has much less to play with here. This applies particularly to any imitation of properties that are (literally) a reflection of the properties of the original, because these are already common to both side of the relationship. But modern technology has given us an additional image property to play with in the form of the image maker. So for example an image maker like a telescope provides the humorist with an intermediate between the image and its casting object. As we see in our example, this intermediate can be made to channel the visual correspondence between the two in new and bizarre ways.

One more question about the relationship between an original and its image: why do we blame every one of the six twists in the O/I family table on the image? Why is the original casting object not responsible for some of the twists? Why is it always the image that is being ‘fickle’ or ‘obstinate’?

The answer comes from our estimation of how real an image is when compared to its casting object. For example, imagine asking a physicist which is more real: a shadow or the object that casts it? The scientific answer has to be that they are equally real. Different of course, but equally real. A total eclipse is just as real as the moon that causes it. Why should we think any different after all?

The oak tree casts its reflection in the lake, but the wind on the water disturbs the reflection, and it takes a while to settle. A nearby boulder sits immobile whilst its shadow chases around it as the sun passes overhead, and its reflection in the lake ripples beguilingly. The tree and the rock are solid then, but images are fleeting, insubstantial and always secondary to their original casting object. The boulder is always there and unchanging, whether in complete darkness or bright sunlight. In the world of Physical Space, images and objects may be equal, but in the world of Social Space, where human nature replaces physical nature, they are not equal. So when there is a break in visual correspondence, we look to the image as the delinquent variable.

How does this compare to the Original/Copy relationship, where there is no visual correspondence, but where there is nevertheless a very strong link between each side of the pairing? Do we always blame the copy in that case too? Well, like the image, the copy is indeed secondary. But unlike the image, the copy is an object in its own right. So it only gets the blame half the time – for example, if the landscape runs in the rain, it is not the copy playing with the norms of nature here, it is the original. So there is no asymmetry of blame in the Original/Copy relationship. But clearly the asymmetry in the Original/Image relationship tells us plenty about how we see the world in human terms.

In our next step in the landscape of meaning, we are going to look at a fun photo that will challenge our model of the joke idea. The issue in this case being, does the joke have to be based on a twist and a legit to be amusing?

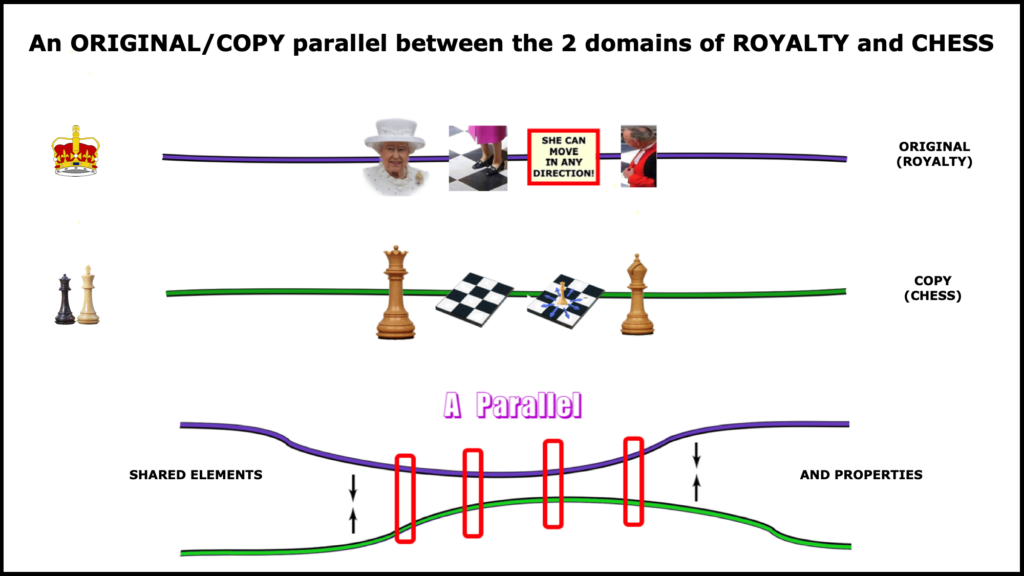

There is no obvious sign of a twist here. But jokes often present us with a puzzle that we have to solve, and there is certainly something to get here. But we know perfectly well that the queen is a mobile being, and that just as clearly, she can ‘move in any direction’, so where is the joke? Well, the directive ‘Be Aware’ is an important prompt in the right direction. It pushes us to spot the parallel with the game of chess, using the two visual cues of the figures and most particularly the floor pattern. Suddenly the caption takes on a new meaning. We are looking at the queen as if she was taking part in a game of chess. (And if we see the churchman as a bishop, then a further link is added to the parallel between the game of chess and the royal family). Or, to put this in graphic form:

Interestingly, this meme had a powerful traction during the time of Brexit, when many hoped that the queen might intervene to sort out the chaos caused by the Conservative party. Certainly the improbable notion that this familiar and quaint little old lady could actually out-move most of the ‘pieces on the board’ was quite amusing in such a context. Just as the contrast between the little old lady and the extreme power of this central chess piece is a dramatic one too.

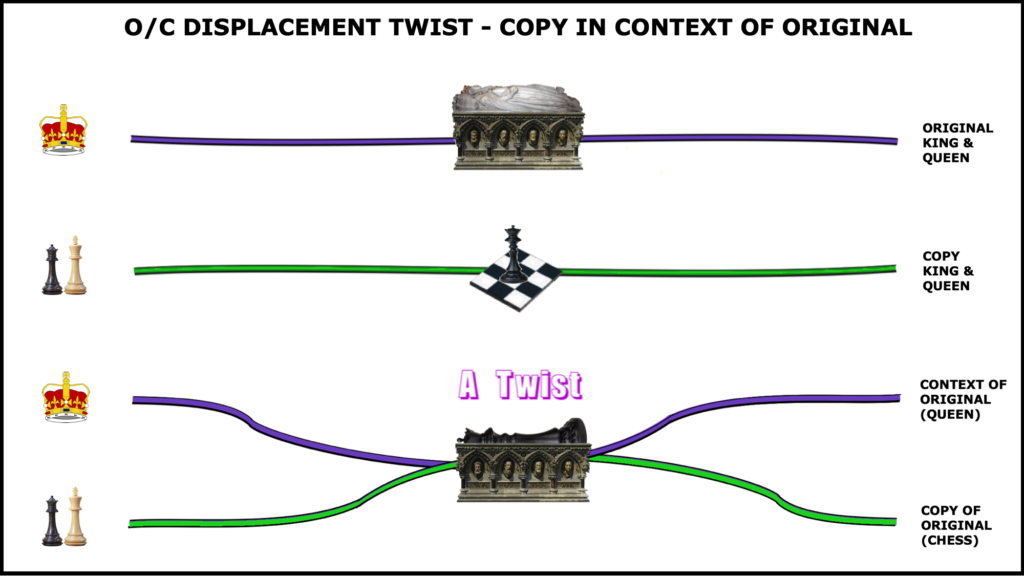

But where is the twist? The queen and the chess piece are straight out of the Original/Copy relationship, but does that make it a twist? For example, compare it with the following picture, where the copy is behaving like its original in a way that is certainly anomalous (it was tempting to put four chess pieces in place of the four human heads, but I managed to resist this further step).

Now although this is a joke idea, it is not funny, even if we add normal tombs in the background for contrast, and insert the surprised face of an onlooker for a visual echo of its absurdity. But it is definitely a real twist, unlike the queen ‘who can move in any direction’ idea. We know this because of the degree of physical integration the chess piece has with the tomb, being literally sunk deep into the context of its original. Two strings of meaning have been combined here to make a proper twist, so it is not the simple parallel we find in the real queen as chess piece example. In fact it is a clear example of a ‘Copy Displaced to the Context of its Original’ twist. Yet despite all this, it is rather less compelling than the more prosaic parallel with the real queen. So let’s see why that might be by looking at exactly how the strings of meaning are configured in both these examples.

First of all, let’s look at the parallel between Queen Elizabeth and the imagined chess piece with a ‘strings of meaning’ graphic.

So this parallel is based upon 3 or even 4 shared elements and properties, but they all stay separate, and together in their own domains, even though they have been pushed together in the picture to create this unlooked for correspondence.

So where does the humour come from? What is so amusing if there is no twist in the scene before us? Well first of all, the parallel made by the picture is a strong one, with three or even four points of commonality that pull the two domains together very effectively (Queen, Board, Moves and Bishop). It also benefits from the way it is presented as a puzzle, because there is fun to be had in its resolution. Additionally, the comparison between the most dominant piece in chess and what is, after all, a little old lady, gives us a paradox that is almost tantamount to a reversal twist. True it is just a suggestion rather than the serious intervention that we find in a real twist, but the contrast between the two is real. Finally, there is the background resonance from the political context of Brexit that plays with our hope of mediation by the real queen. So, all in all, this makes a rich combination of meanings that together are likely to bring a good smile to that inward eye that we all use to find our way around the landscape of meaning.

As there is no twist, it might seem like there is no need for a legit. But the comparison has to make sense nonetheless, and it does so comfortably, given the number of commonalities between these two very different dimensions of meaning. The parallel makes sense because it is a strong one therefore. What about that other example with the Chess Queen as Tomb top though? Where is the legit in that picture? Because there should be one, given there is no other measure of support to this displacement twist. However, nothing that helps it make sense is offered us, and the joke idea is much poorer for its absence. Try as I might, I cannot find a way (as in for example a pun) that then unites these two domains of royalty and chess to make any sense of the displacement. Which means that as long as we fail to find a legit for this cartoon idea, the twist falls short of being an amusing idea.

On the other hand, the ‘Be Aware. She Can Move in Any Direction’ scene is truly amusing. Because there we find a rich wealth of parallel meaning, and even though there is no twist actually combining the original and copy strings of meaning, its colourful bundle of ideas is more than enough to make us smile.

What do we make of this? Well, in the context of the ‘Be Aware’ joke idea, we see that a parallel is caused by pulling two strings of meaning together, using commonalities that may be as striking as they are fanciful. It may not force the two domains together so hard that they fuse in a twist, but it uses a semantic force that can be dramatic, poetic or in this case, amusing.

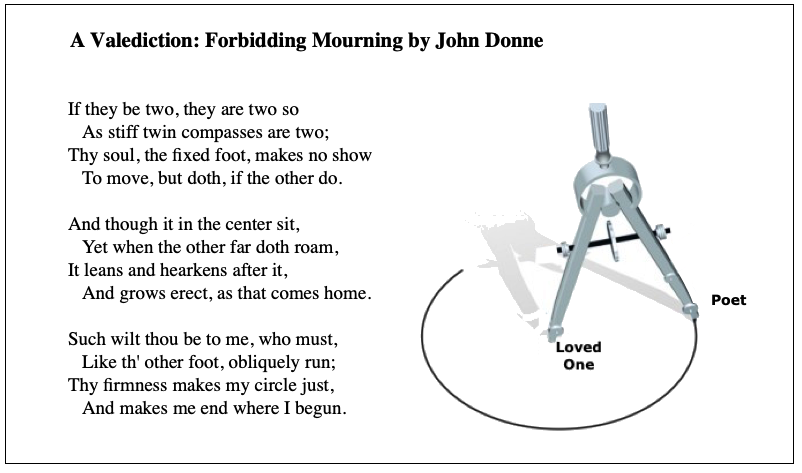

The logic of both the parallel and the twist are clearly in use outside of humour. The creators of art, poetry, political speeches, music and film all use these techniques to produce compelling forms of meaning. For example, and this is one of my favourite poetic conceits, the parallel between a poet’s love for his wife, and a humble twin compass positively exults in far-fetched and yet cleverly appropriate commonalities.

Having written about their two souls being as one (in another conceit where the pair are likened to a leaf of beaten gold), John Donne then seems to concede that they are two separate souls in reality. But not really, because he quickly moves on to show they are one after all, fused together as the twin legs of a compass.

There is no question that the description of the one side leaning towards its lover as it moves further away, and then growing erect as it comes home, is a brilliant display of visual and verbal footwork. A display followed by the poet putting away a Maradona type goal in the last verse, where he uses the closing of the perfectly drawn circle to affirm the strength and quality of their relationship.

So the first time I came across this passage, I marvelled at the narrative power of its image and follow-through and was more than happy to smile at the sheer quality of its inventive bravura. But although it made me smile, I was also clear that this was no joke. Rather, it was a profound, albeit wonderfully clever, attempt to make as compelling a message as the poet was able to create for his wife in his unfortunate and prolonged absence. A situation very different then from the queen and the chess set parallel, for in that case it is perfectly clear that the intention is to amuse. So how do we recognise this serious difference?

Humans read each others intentions all the time. We also help that along by deliberately broadcasting our intentions when that is helpful to either ourselves or our audience. So jokes announce themselves in a number of standard ways. A cartoon normally has a well-recognised context in its place in a publication, so we know what to expect, but a visual meme on Facebook has to be looked at more closely, as there the context is no guide, given the many kinds of graphics that are shared by people. For example, in the next cartoon, it is clear that this is humour, and not knowing that it comes from that famous source of British cartoons, Punch magazine, makes no difference in this case.

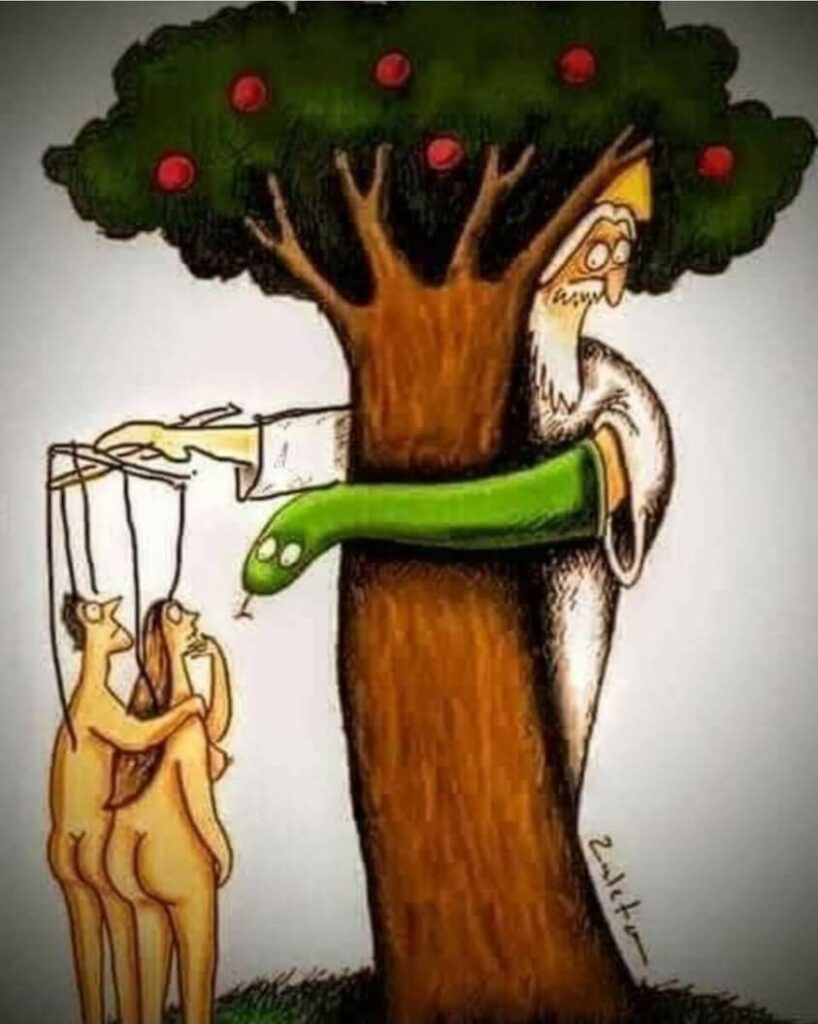

So the priest is just the puppet of that great puppeteer in the sky, and the joke idea is therefore an Original revealed as Copy through the artifice of a ‘Copy like Original’ imitation twist. The legit is based in the visual authority of the drawing, Whilst the fact that the godly master lives high above us all makes the picture of the ascending puppet strings consistent with the puppet master. But now look at this next example, pulled from a Facebook page.

The picture is clever in the way it takes our eyes to the naked bodies first, and next to the snake, via their facial attention and the prominent colouring and size of its body. Only then do we spot the third factor in the situation and understand the double level of manipulation behind the scenes. But is this a joke? Because it comes with the footnote:

A picture is worth a thousand years of pointless biblical scholarship.

And it appears under the sponsorship of ‘Atheist Alliance International’, who are certainly capable of being humorous about religious hubris, but always with the aim of exposing the credulity of its believers. So let us be clear. If we had found this picture in Punch, then it would be seen as a joke. Not as succinct as the previous example with the priest perhaps, but an idea clearly intended to amuse. But here on the Facebook page, things are less clear, and it is up to the reader to decide for themselves how they are going to take it. Because the territory between pure jokes and satire is continuous, and if there are no outright pointers to the intentions of the creator, then we have to make up our own minds, or change the page.

We have been treading lightly so far. As observers in both the valley of shadows and reflections and copy plateau, we have seen a lot, but we have not thought to dig in, and actually change these realms in any way. We have understood much, but we have not tested that understanding in the special way that makes such an important difference between conjecture and real science. True, we have faced the reality of both humour and the nature of meaning at the sharp end by looking at real examples, and that counts for a lot. But we now face the acid test, which is what every cartoonist faces every day when they sit down before their drawing board. The test is not the drawing itself, because that is mainly presentation, but the conception of the idea that the drawing must entirely rest upon.

Bill Hewison, the cartoon editor of Punch magazine, who wrote a nice little book called ‘The Cartoon Connection’ suggested that the following words should be carved in granite outside the Punch office:

Like many of the books for aspirant cartoonists, this one has a chapter where its writer tries to discuss the creative process involved in thinking up new ideas. What the cartoonist Langdon referred to as ‘Controlled Mind Wandering’. A clue which is frankly as near as we ever get in the humorist literature, because although they all agree that it is critical to know how to create new ideas, none of them have any real advice to offer. Apart that is from say looking at the work of others and refilling that glass of wine.

What about the philosophers and psychologists? What do they tell us about ‘the act of creation’? Again, rather little. Because to even begin to work out a path to the creation of a joke, we need to have a good understanding of how jokes work, and this means applying that working model to a significant number of actual examples. Nor does it end there, because as we now know, the nature of the area twisted by the joke plays a major defining role over the supposedly transcendent definition of the joke dynamics. For example, to understand how a joke plays in its natural habitat of the valley of shadows and reflections, we have to know as much about visual correspondence as we do about the nature of the twist and legit. So although the idea of the twist and legit is relatively simple, it is the identity of the relationship that both the twist and legit are based upon that is so critical to making real progress in our understanding of humour, and meaning in general.

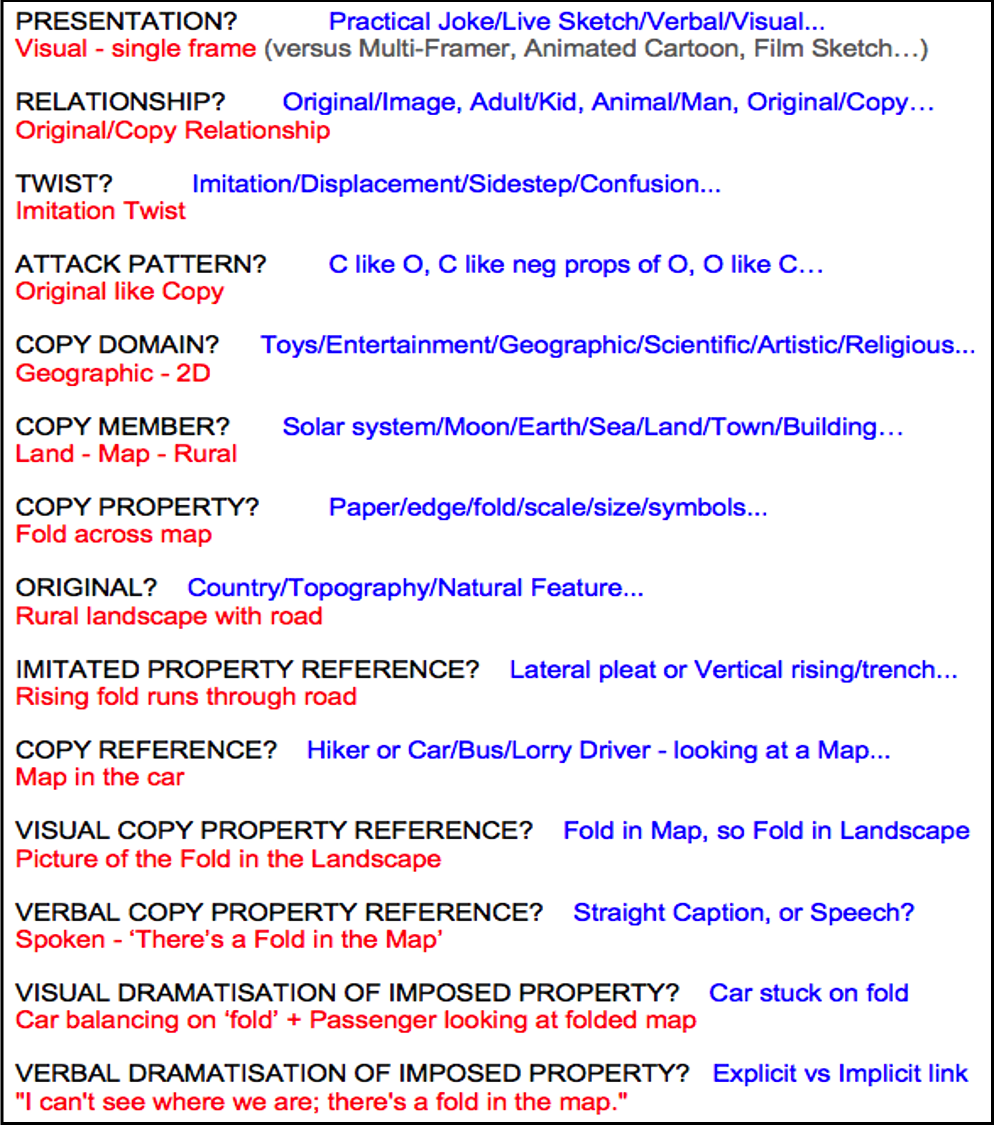

So let us now make a steep climb and actually add something to the landscape of the imagination. To wit, let us make up a joke from scratch, but using our insights into, in this case, the O/C relationship to create a joke idea step by step. But where to start? Well, if we choose the copy plateau as our source of a twist, then let’s go for a straightforward imitation twist shall we? What about ‘Original like Copy’ as that is usually more of a twist than its more obvious opposite (reversal is more powerful than exaggeration), so now we need an example. And by now, our path has got us to the choice of Copy Domain, as we can see below in this table of further steps that we need to take to create our new cartoon.

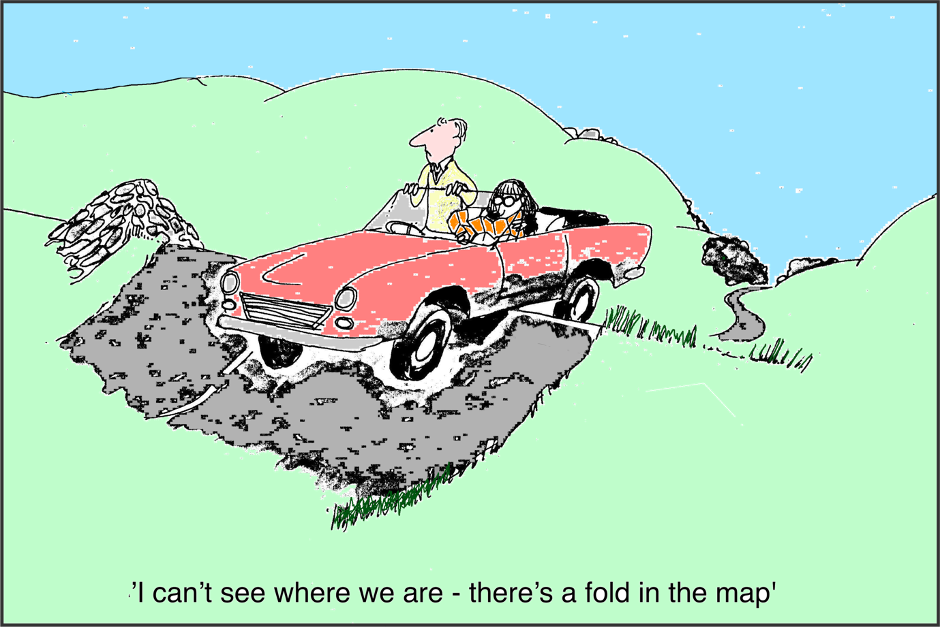

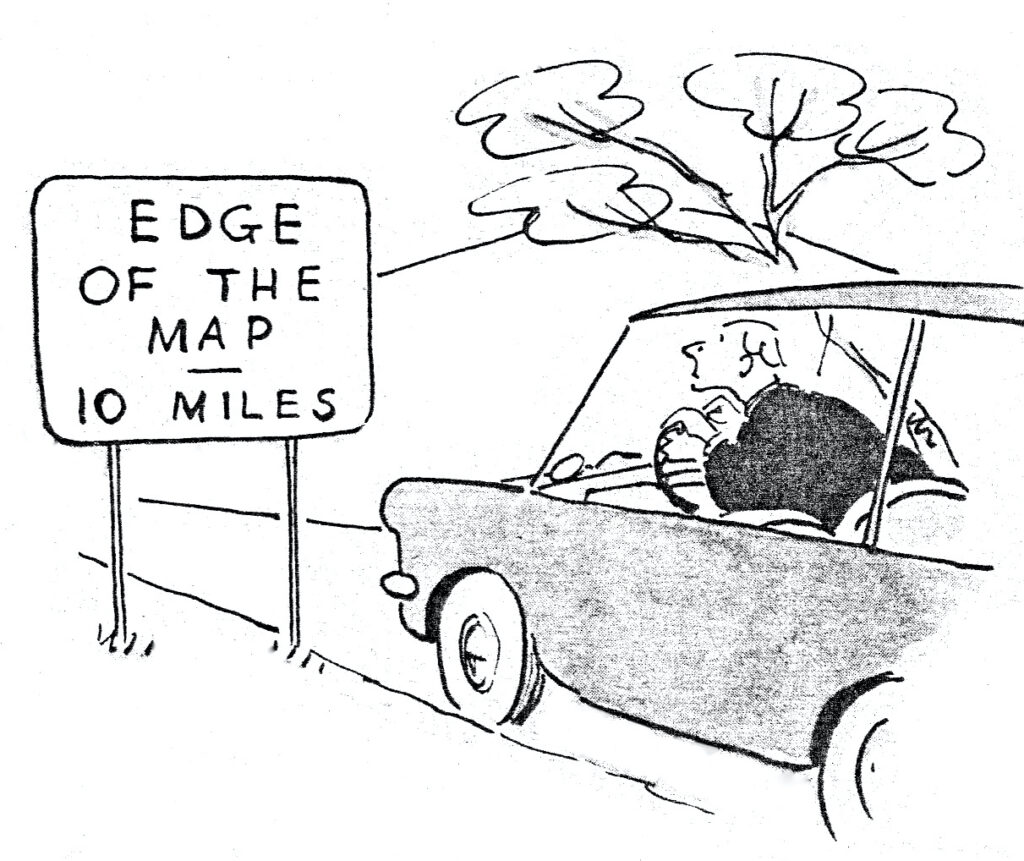

In choosing Geographic, we open up the world of maps and globes in all their various scales, styles and locations. We go for a simple road map and choose a copy property. In this case, that road maps are folded. Next, the original that will have to take on this property. Being a map, the obvious option is a landscape of some kind. Which means we now have our official O/C pairing of landscape and map. A rural scene in this case, as that may be simpler to draw than a complex urban one, and sight lines are easier to maintain in open areas. So, the landscape is going to take on the property of the map, which in this case is a fold of some sort. But at this point, it is vital that we make a copy reference, or the relationship being twisted will be unclear. Remember, twists on originals do not instantly summon thoughts of the O/C relationship to our mind (although the presence of a copy in the opposite imitation twist does exactly that). Meaning we need somebody holding a map, probably in a car (soft top best for visibility). Clearly a caption would help to underline this reference: as in for example ‘There’s a fold in the map’. To dramatize the verbal side in the caption, the passenger with the map can complain that she can’t see where they are due to this fold in the map. To dramatize the visual presentation, we can exaggerate the fold, so the car is left swinging on its edge, and this also serves to freeze frame the whole situation.

A critical look at the table will reveal that there is rather more to this creative path than we get to see in this apparently nice clean presentation of step-by-step logic. Though it is certainly the case that I arrived at this cartoon idea by thinking along these pathways. However, this was in response to a dual need: to create a cartoon certainly; but do so by also creating what looks like a viable path to its realisation. In other words, the table is itself a creation. Am I arguing that it is also a fiction in that case? To some extent yes. But one that lays the ground for future algorithms? Well, maybe.

However, any professional cartoonist will surely bear witness to the considerable complexity that ‘controlled mind wandering’ really involves, Because they know very well about the considerable fall-out of ideas that never make it as jokes. Ideas that disappear into the waste bin under the all-purpose category of ‘failure to fit’. Nor do we need to go to outside our own findings on humour to see the problem. Because if we try to pin down our O/C relationship in any more detail, for example, with the idea of mapping where its inhabitants belong on that plateau, we come up short. Yes, we can present the colloquial categories of such examples as toys, art and so on in a picture like the one already presented on this walk, showing the various shops in a town as if this was a systematic view, but this is no more useful than the graphic below:

But all science starts with simple steps. Imagine the situation if the father of genetics, Gregor Mendel, had known about just how complicated inheritance really was, through some magical glimpse into the future. He would suddenly have become too sophisticated and too embarrassed to make any such simple-minded assertions – as he in fact then rightly did make. And just imagine if his friends and colleagues had also had the same revealing glimpse into the bottomless pit of complexity that is modern genetics. It would have been more or less impossible for Mendel to present a simple set of ideas to them as if these ideas were then worthy of their attention. Which is exactly the situation that a scientist of meaning finds himself in when he begins to propose a set of simple ideas to a body of people who are total intuitive experts at finding their way around the landscape of meaning. A place that is, after all, their natural and every day home. Because the damning ‘So What?’ that comes from this elevated position is ever hovering above such attempts to map the logic of existence. Making for one hell of a challenge to add to the great complexity that already faces any cartographer trying to find their way in the landscape of meaning.

We also know that these simple steps to creating a creative path to a joke are going to look way too simple to the minds of the future, but we have to start somehow. Indeed, like Mendel, we have to look for areas that are relatively simple hoping that they will lead to a good look at what is really going on underneath. So just as Mendel managed to find half a dozen characteristics of pea plants that were not bedevilled by serious complications (like being co dominant or a part of a coadapted gene complex), we are obliged to seek out an area of meaning that is reasonably contained, shallow and hopefully colourful as well. Rather like dipping our net or camera into a nice rock pool, safe from the crashing waves and swirling tidal currents of the ocean just nearby. Which is what these cartoons on images and copies really represent here. Two areas of humour with enough of a physical existence for us to get a proper fix on them, and without going deep offshore, into the ocean of tidal beliefs and swirling values that is the real core of the human condition.