Human Sciences Faculty

Oxford University

General Paper

2pm Friday June 14, 2030

You have 3 hours

Please use the attached cartoon stack as your main source of reference

Answer here

THE FIRST QUESTION IS COMPULSORY

1) Can there ever be a general theory of meaning on a par with the explanatory power of Darwins theory of evolution? What challenges would it have to overcome, and what might serve as the basis for such a theory?

The debate about a general theory of meaning in the 2020 Manifesto begins with the question: Will there ever be a Darwin of the social sciences, and if so, what will their theory have to say about human life that we don’t intuitively know already? It then sets about answering this question by proposing a controversial view of the importance of Darwin’s theory. The idea being that in order to make a fair comparison between the biological and the social sciences, we need to assess just how revolutionary the theory of evolution really was to begin with. So first we must look at Darwin’s theory in this new light, and then we must look at how this view leads to a useful comparison that sheds light on a possible theory of meaning.

Nobody in their right mind would argue that Darwin was not a very great thinker (few these days read the ‘Origin’, but for those who do, the impact is immediate and sustained). However, it may also be true that Darwin proposed a set of ideas that were relatively simple in their description of the natural order. A truth that may be hard to recognise because, against the backdrop of those times, the ideas of both Darwin and Wallace represented a hugely controversial force that made them appear many times their actual size. But the question raised by the 2020M was not about how revolutionary the idea of evolution was on the social level. Instead, it looked at the idea from the intellectual and even common sense standpoint. The question simply being, was the idea of evolution as much of a challenge to our intellect as it obviously was (and still is) to our cherished beliefs?

For example, just how hard is it to see that animals and plants have changed as a result of the natural forces present in the environment? To start with, we already know that humans have been selectively breeding animals and plants for many thousands of years, so if we puny humans can change plants and animals as much as we have, then it stands to reason that the greater powers of Nature must also have the same effect. Mother Nature has the power to water the seeds, leave them parched, or drown them, forcing its offspring to adapt or die in the process. So it is easy to see that Nature is busy selecting for and against features of both animals and plants, just as we humans have more recently learnt to do with our somewhat lesser powers. The idea that Nature is the agency of change, just as we are, is not a controversial one. Indeed, with a view free from metaphysical belief, what else could explain away our own human ability to change the nature of the animals and plants we live on for our greater benefit? We know we do it, and we know that Nature is more powerful than us, so the conclusion that Nature does it too is hard to avoid. Nature changes itself.

Another example. Is it really that hard to imagine we are related to the great apes? Because although the question of change is a serious issue, it seems that the issue of relatedness provokes even more anger and indignation. After all, Darwin didn’t just propose that Nature is a powerful force that can change species. He also pointed out that we are basically apes, and therefore related to the gorilla or chimpanzee, as we all share a common ancestor. But again, if we look at this idea without our own subjectivity and religious belief getting in the way, then there is really nothing strange about this proposal at all. Only stand in front of a caged gorilla and look into its eyes, and the sense of recognition that then ensues, and that is on both sides of those bars, is quite startling. True it is black, but then many of us humans are black. Hairier than us, but that’s a simple question of degree. Stronger certainly, and more bestial looking, given its lack of physical fragility, but those eyes, and what really does feel and look like an enquiring mind behind them, are surely more than enough to make us concede that there could be a physical link between us. Well, it is true that in Darwin’s time, few may have experienced this directly, but surely even a picture gets us close enough to see the startling resemblance between man and ape, so the idea of relatedness between us is hardly far fetched.

Where then does this leave our appraisal of the idea of change and relatedness sponsored by Darwin and Wallace? Well, it seems that once these observations are removed from their religious context, they turn out to be a set of relatively simple and uncontroversial ideas. Ideas that provide us with an excellent doorway to the whole new science of Biology, but hardly a set of ideas that tells us the whole story, or even 1% of the story of life on earth. No wonder though, that it is tempting to talk about the early ideas of Darwin as presenting us with the whole picture, bar a little colouring in that is. Because it is precisely the extreme reaction from the church that has cast his ideas in such a giant silhouette after its otherwise modest emergence in the bookstalls. Making it almost impossible for us to see the ‘Origin’ for what it is. Which is a picture that needs a great deal more than just ‘a little colouring in’ for a start. Because a very large part of the actual image is missing as well, and along with it, almost all the details that we now recognise as telling us the enormously complex and multi levelled history of life on planet Earth that is modern Biology. So not then a finished picture, nor even a colouring in picture, with just the outlines showing, but a simple beginning revealing some useful shapes, which in retrospect will father an important part of our knowledge in Biology.

This assessment of the effect of the church on the idea of evolution is graphically presented in the 2020M, where a cartoon drawing of a statue of Darwin in the museum of Natural History in London is shown casting a huge shadow on the wall behind him. The shadow is far larger than the seated figure of Darwin because of the particular angle and intensity of the light at the foot of the stairs, looking up at him. The point being that a fierce and low level force can hugely exaggerate the size of a what turns out to be a relatively unassuming set of ideas in the light of normal daytime illumination.

So let’s say the ideas put forward by Darwin were relatively simple, and imagine that a general theory of meaning might start out in the same way. That is, such a theory might start out with what, in retrospect, could seem like a rather simple set of propositions. But here we encounter a minefield. Because unlike the unfamiliar landscape of a jungle or a set of islands in the Pacific, the landscape of meaning is our natural home, and therefore entirely familiar to us in all its detail. Which means that any simple start we make in mapping its features and logic is going to be subjected to an intense and withering scrutiny, the like of which will discourage even the most dynamic and Panglossian examples of ‘push the boat out’ science. Because it is not just ‘in retrospect’ that this initial foray is going to look simplistic and superficial. Rather, it is right away, in the immediate present, that our geographers of meaning are going to appear banal and simple minded. Because telling people what they know already (and as if they didn’t know it), is not going to go down well. A problem that becomes even more severe when we realise that one of the people likely to be the least impressed and the most disillusioned by such an approach is the very person trying to map the landscape in the first place. Because it is not an easy task creating the first maps of meaning, when these are seen by others as childish. So what can we do about this problem?

2) Use the following picture, with its two alternative scenarios, to explore how humans allot credit to our actions. How does this reflect on the more general problem of a theory of meaning, especially in light of the {waiver} problem?

Scenario 1

Imagine attending an important lecture in which the organiser has to go up on stage, and announce that the speaker has been obliged to cancel at the last minute, because of a sudden illness. The auditorium is packed with a large crowd, who are waiting expectantly. So the organiser asks whether perhaps there is somebody in the audience who could substitute for the guest speaker. A profound silence descends on the hall, as everybody looks around to see if there is anyone willing to respond to such a rare and challenging request.

A young man stands up. He is unknown in the field, but after a hasty consultation with some experts at the front of the hall, and excited murmurings amongst the audience, he is introduced to the throng. It seems that English is not his first language, and as he begins what is clearly going to be an entirely unprepared talk on religious belief systems, a hush once more descends. His presentation is quietly confident. Within just a few minutes, he has presented a concise summary of the ideas of the absent speaker, and paid humble tribute to his insights. He then begs leave to add a few ideas of his own to this established body of thought. It is within the space of the next few minutes that the audience begins to realise that they are witnessing far more than just the spontaneous ideas of a young post grad student. His diction is clear, colourful, and very well informed. His ideas are original, challenging and in some ways, quite simply surprising. Somehow, and despite his hesitancy in addressing such an august company, along with his obvious difficulty in producing fluent English, a new and important synthesis is emerging in front of their very eyes, and one that makes the ideas of the absent speaker look plain and simple. And all of this in the face of the huge knee quaking challenge of creating a lecture from thin air. Whilst coming from a person who has already admitted to never having given a lecture in his entire life.

At last, after heartfelt thanks for the attention of the audience and apologies for his obvious lack of experience in presenting his ideas, along with the hope that the absent speaker recovers soon, the speaker takes his leave. Modestly neglecting to mention who he is, and having avoided all attempts to gain credit in any way throughout this entire performance, he now quietly retires through the stage door, from whence he does not reappear, despite massive and stunned applause.

Scenario 2

The speaker is not ill, and appears before the throng, but only after he has arranged for another distinguished figure to announce his entire list of life achievements and successes at the lectern first. His appearance shows a calculated balance between looking smart, whilst nevertheless being an academic, and therefore above such earthly matters as dress and appearance. So he sports a beard, but it is clipped to perfection, and his tweed jacket sports elbow patches, but rather smart ones, with the jacket being rather too well cut for a man above slavish fashion. The applause having subsided, he strikes a pose at the lecturn, and begins with a loud confident voice. But despite the fact that he has given this speech many times before, we see that he is reading it aloud from a prompt, and that much of it comes ‘pulled’ from his one, and rather out of date book. He ‘improvises’ a joke here and there, but many have heard this same litany before, and are unimpressed. Some time is wasted putting down others in his field, which he does with a mixture of faint praise and patronising comments, and without engaging with their principal ideas. Periodically, he slaps his own back with approval, indulging an ill concealed delight with his own ‘tentative contributions’ as he calls them, though there is nothing tentative about his manner at all. Dropping as many famous names as possible, he attempts to give the impression that religious leaders around the world are almost queuing up for his advice on religious matters, and that this, along with his meeting important political figures, leaves him far too busy to have the time to write another book at the moment. A fact that is perhaps intended to excite sympathy, and even a feeling of loss amongst the assembled listeners… He finishes with a flourish, as if the whole effort has been a marathon of intellectual virtuosity, and waits pointedly for the applause, which is slow in coming because his finish took them by surprise (half the audience are asleep). He winks knowingly at several young ladies in the front row, uses his arms to sign for a subsidence in the slightly forced applause before it dribbles out to nothing, and asks if there are any questions. There is an embarrassed silence, and the distinguished figure is forced to get up, and thank the guest speaker effusively, before once again, an applause is made, of very short duration, as the audience quickly obliges, in order to get up and go. The speaker is left standing on the stage with his supporting retinue, who congratulate him whilst he looks around for the pretty young things in the front row who have long since disappeared.

2) Comment on the quality and the extent of meaning in the following artefact.

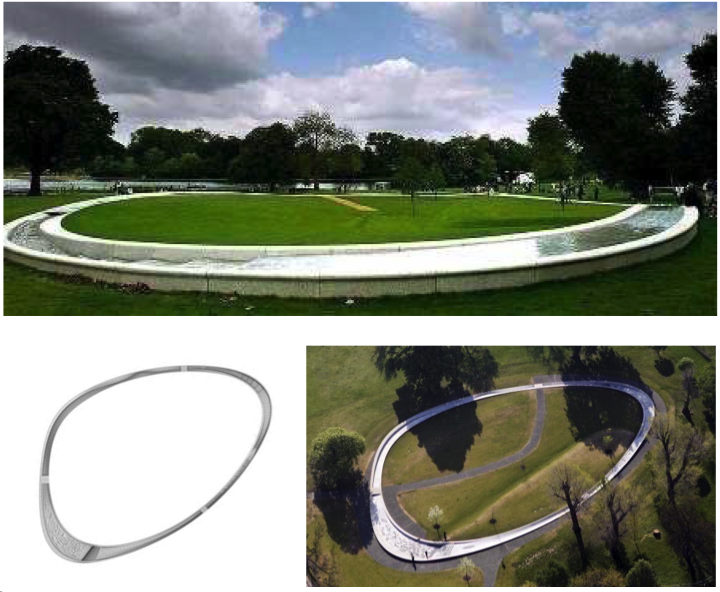

Below is a photo of the Princess Diana Memorial Fountain in Hyde Park, London, which was opened in 2004. It is made entirely of granite, and is more or less oval in shape. As such, it hugs the terrain, rather than standing out from it. Water rises into it at the highest point, and then runs down, on both sides, to sink away, out of sight, at the wide curve in the background of the first picture.

In the summer, people and their kids paddle in the lower reaches, where the water is deeper, and it is a very popular place to visit, with or without children. It was paid for out of the Diana memorial fund, which raised more than £72 million, £5 million of which went to the design and building of the fountain itself. The Gustafson Porter design expresses the concept of ‘Reaching Out-Letting In’. This is based on the qualities of the Princess of Wales that were most loved, her inclusiveness and her accessibility.

In the following detail shots, we see some of the various surface types cut into the granite curves, as they swish the water down to the lower reach. Here are three sample shots of the East side of the oval. Closely followed by three further shots of the West side, where the path taken by the water seems less peaceful.

The contrast between the two sides is intended to show the two sides of Diana’s life: happy times, and turmoil.