Status Twists On The Original/Copy Relationship

The ‘Reverse Status’ Twist

1) The Original is devalued

Another aspect of the original/copy relationship that can be attacked by humour is the relatively low status of the copy compared to its original. A low status because whereas the original has an existence independent of its copy, the copy relies on the original – totally – for its identity and existence. It is therefore natural to view the copy as nothing more than an adjunct of its original. That is, the original has a superior status to its copy due to its prior existence. Which is precisely the assumption that humour plays with in the ‘reverse status’ twist, creating a situation where the copy is superior to its original. An assumption that can be challenged in two ways: either the status of the original can be devalued, or the status of the copy can be elevated.

Lewis Carroll tells an engaging story in ‘Sylvie and Bruno Concluded’ which provides us with a verbal example of this twist (after all, there is no need to stick exclusively to cartoons in this analysis: the model works perfectly well with all forms of joke presentation). So, the story in question features a country where the cartographers are very keen to create the perfect map. They experiment with larger and larger scales until of course, eventually, they end up making a map with a scale of a mile to a mile. The German professor who is explaining this, goes on to say:

‘It has never been spread out, yet. The farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So now we use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.’

What Carroll does first in this story is to ‘improve’ the map by taking it far beyond its normal commitment to being a relatively small scale, and therefore easy to handle and carry around form of copy. Because by making the map larger, it takes on one of the negative properties of its original in the process: namely its scale. This is therefore an exaggeration, not a reversal, but it takes the map to the point of absurdity (this is the humourous equivalent of the ‘reductio ad absurdem’ used in some verbal arguements). And the reason the writer uses this imitation twist, whereby the map gets closer and closer to the scale of the original landscape, is that it then leads us to the ultimately extreme development of the map, and its subsequent dismissal by the farming community. A dismissal that actually results in the original being downgraded (‘it does nearly as well’), rather than the map being upgraded, because the map has become a problem for the farmers. Meaning that the landscape is judged by reference to the dismissed giant map rather than the other way round. So Carroll evaluates the original from the standpoint of the copy, which is the reverse of normal practice, and this downgrades the original landscape in favour of the map, which is patently absurd, and therefore exactly the outcome desired by its author.

The first twist in this tale is therefore an imitation twist, where the copy takes on a property of its original. In this case, the property is a negative one because part of the copy advantage of the map is the fact that it reduces the scale to a manageable size (it also removes the third dimension, but that is not the issue here). And because this is apparently done progressively in the story, the twist dynamic is shown with a number of arrows to suggest further experimentation up to the point where the geographers reach their final goal of 1:1. This need for ‘improvement’ is the basis for the legit, as we have seen before in the wig cartoon, and it is not only in marketing and sales that we find this modern compulsion to make things better. All of which affords the cartoonist plenty of scope for legitimising crazy attempts with absurd outcomes, all in the name of progress.

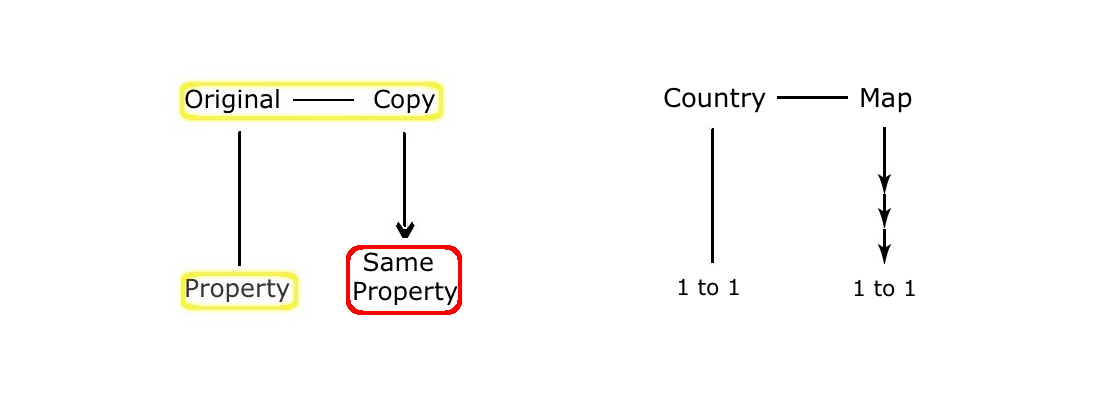

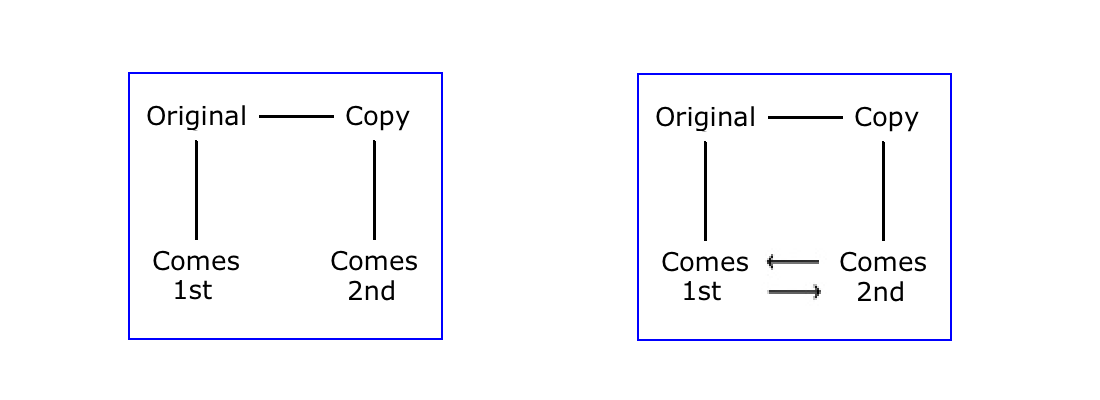

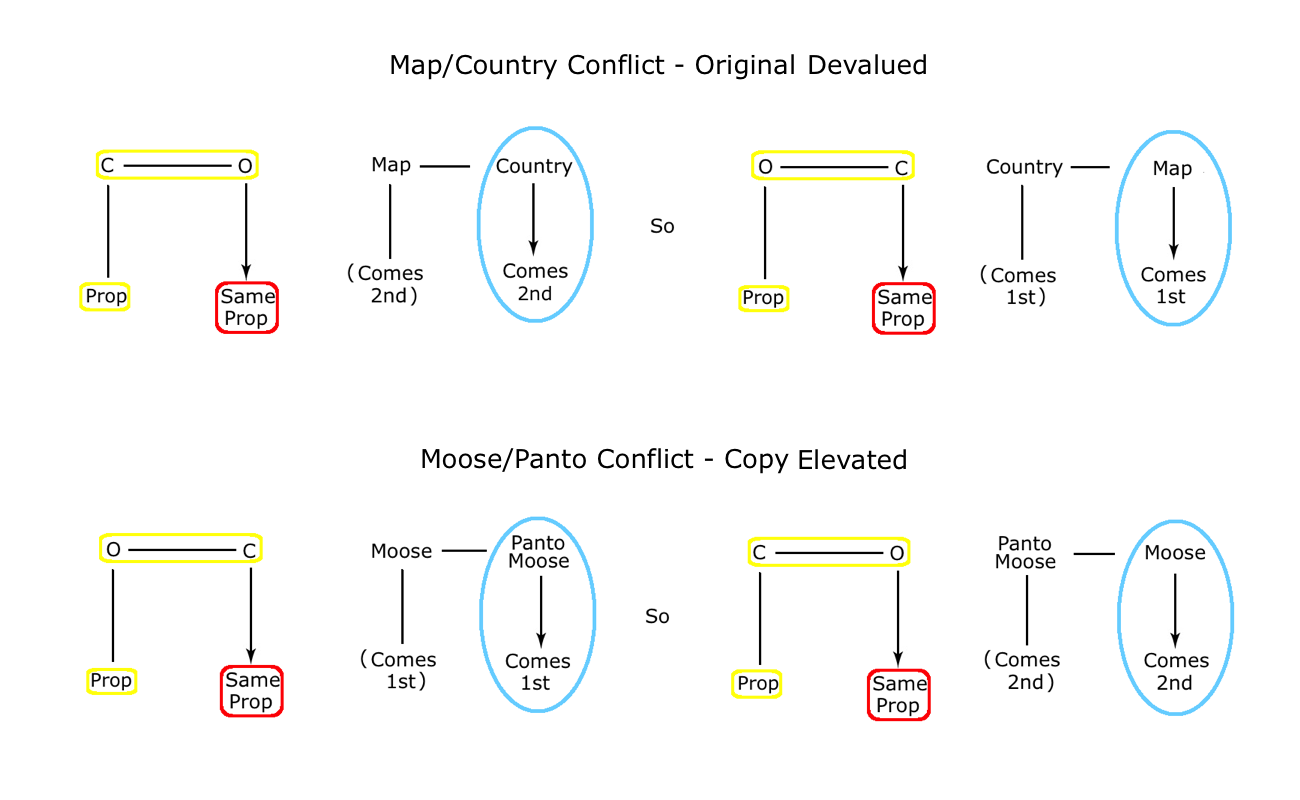

The negative property imitation twist is, by, now familiar ground. But what about the evaluation twist, whereby the map is effectively judged as the lesser of the Original/Copy pair? For example, is this similar to the Reverse Status twist that we came across with two of the puns presented in the section on the pun? Where the under dog Brits triumph over the uber dog Americans, and the underdog wife gains ascendancy over her husband? Well, it seems like a long way from such issues as nationality and gender, but the basics of a judgement or action that reverses the normal status quo seem comparable. It is just that here the upset is about an entirely intellectual matter, with no ethical or political concerns to be found in the vicinity. It is simply about the relative primacy of the original over the copy. A primacy that is based on the simple claim of coming first, both logically and practically. Or to put this as a relationship that translates into a diagram of the norm, and then its reversal:

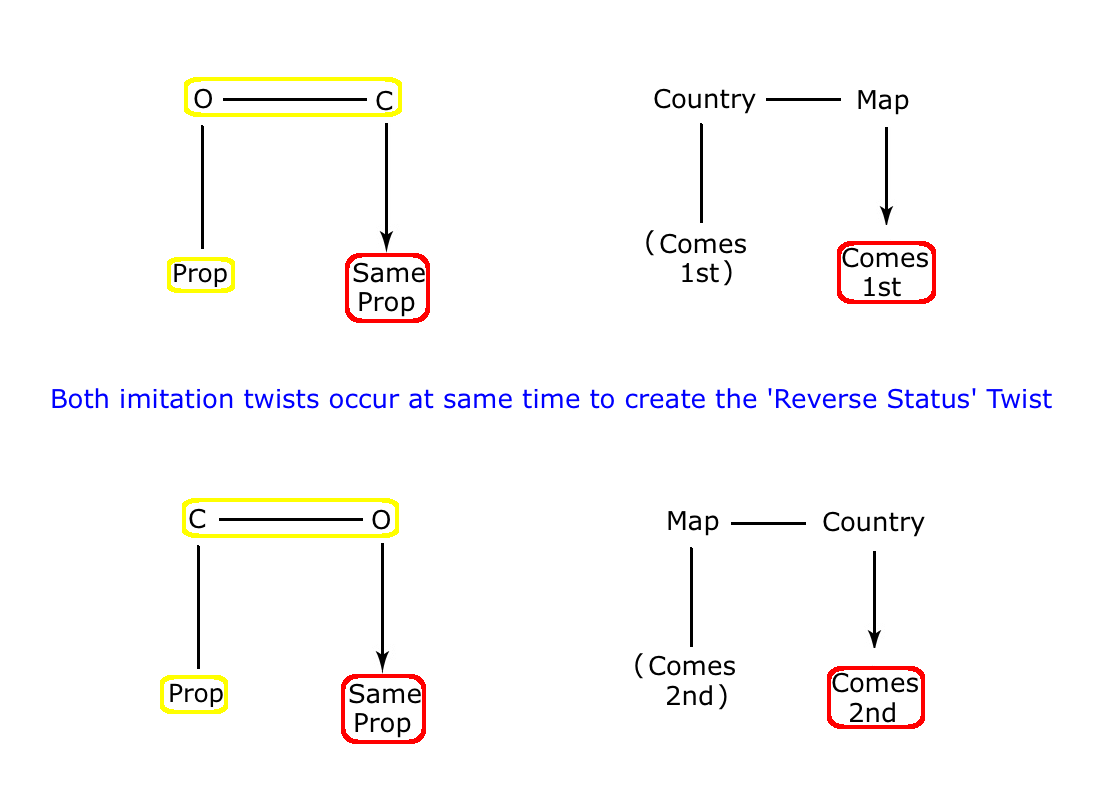

The question here is how can this reversal twist be drawn up using the same terms of reference that have been established for other O/C twists? Well, the simplest way to do this is describe the switch as two imitation twists actioned at the same time so that the result is a reversal. This is clear in the following diagram.

So the logic of the reversal/downgrade is that once the map has been made to resemble its original as much as possible, it can be compared with its original on equal terms. At which point, the original can be made to come not first, but second, in the comparison between the two. Whereas, if the original had been competing with the normally much smaller map, then there would have been no room for manoeuvre, as the primacy of the original is hard to contest. After all, the map is merely a hugely simplified, and much diminished, version of its original landscape, so there is no way in which the landscape could be considered as a poor version of the map in what are the normally accepted terms of the O/C relationship.

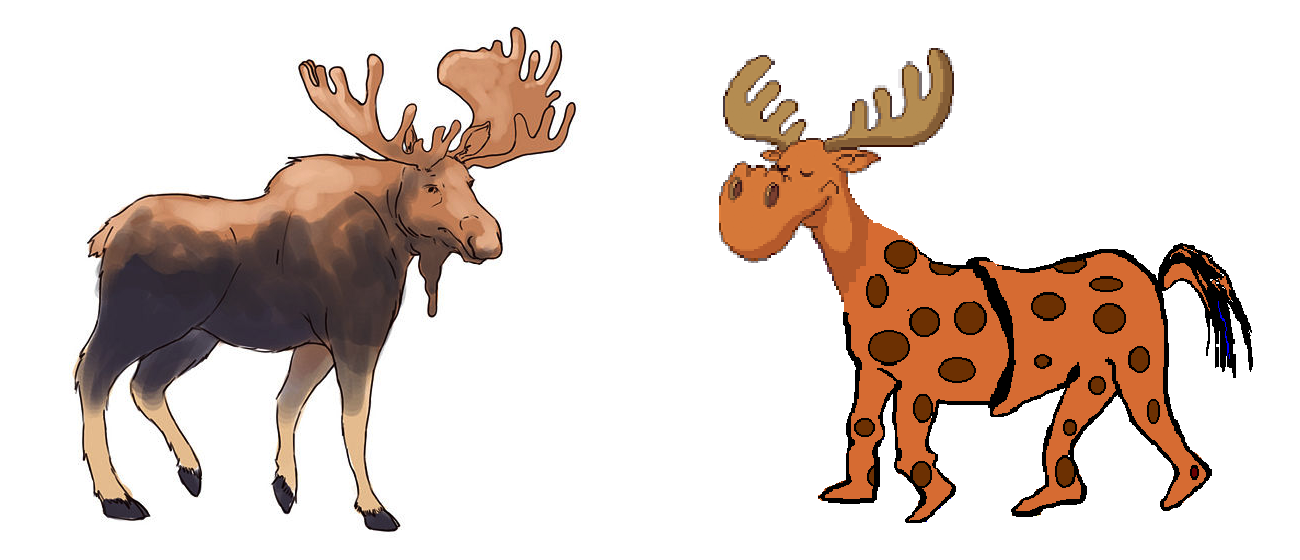

Now let us look at an example where it is the copy that is elevated above the original, rather than where the original is degraded. So, in an example from Woody Allen, we are told an amusing story about a moose hunt, which ends up in a fancy dress competition, where a pantomime moose actually wins the competition despite the fact that a real-live moose is competing as well (having somehow regained consciousness after the hunt). Understandably, the real moose is very unhappy about the panto moose winning, so the two of them lock antlers in the living room (in what is an archetypal ‘original versus copy’ struggle for primacy). We don’t get to hear the result, but the main point is that the conflict is caused by the reversal in the O/C evaluation, whereby the copy is elevated above the real moose, to win the competition.

One reason this example is interesting is because, this time round, the reversal of status is approached from the other direction. So instead of lowering the status of the higher of the two, as in the previous case, the position of the lower member of the pair is elevated. The moose suit is lifted to the status of a real moose (and then beyond it) by the judgement of the fancy dress panel, whereas in the map example, the landscape is pulled down to the position of its copy (and then further down), by virtue of the judgement issued by the country’s top court. Quite how we can show this difference in the diagram, along with everything else, is not entirely clear however. But perhaps just by putting the sequence of copy to original (as in the map diagram), the other way round for the moose twist, this would make the point. Which is what we see below – with the blue scoops catching the twist result to make the comparison easy to see.

Notice that by putting a real moose into the context of its copy (the fancy dress party), Allen has put a displacement twist into the story (Original displaced to the Context of the Copy). Fancy dress parties are not the normal habitat for a wild moose, but the hunter who bagged the moose decides on a bit of fun, when suddenly, and unexpectedly, the moose wakes up. Incidentally, the legit for this displacement is that the owner of the moose was looking for amusement. Making this a good example of how the need for amusement can justify its own results – humour can, it seems, be its own legit. And the legit to justify the moose suit winning over its original? Well, it was human judgement, and we all know how reliable that can be. Which is also what we find in the map story: we are assured that the landscape does ‘nearly as well’, which is just another judgement that we are again prepared to take largely on trust (though the map would kill the crops, so the farmers complaint is a good reason for dismissal).

If the copy can best its original, does it also follow that the ‘Reverse Status’ twist can have an opposite, where the original bests its copy, so that the original turns out to be even more superior to its copy than before? Well, the original going further up the scale of value is an option in principle, but perhaps this is less interesting, due to the difference already discussed between Exaggeration and Reversal. Namely, that it is the reversal that creates the worthwhile twist, and what we are proposing here would just amount to a bit of exaggeration. Which is not to say that exaggeration does not take the logic of a situation further (in the same direction), thus ensuring a departure from normal logic. But it is often quite easy to stretch things out a bit, whereas flipping them on their head to create a reversal is another matter. Note that the former can lead to the latter as well. So in the map story, Carroll starts by stretching out the map in greater and greater steps, allowing the situation to get to the point where a status reversal (which is otherwise hard to justify) can be more easily stage-managed.

Coming back to the question of whether it is possible to flip a ‘Reverse Status’ on its head, there is one way in which this might be achieved. Namely, by knocking down the copy whilst keeping the original on its pedestal. And maybe the best way to devalue a copy is to do so by comparing it to a variant copy of the same original? Which means looking for an area where originals have different and alternative copies – as in Art. Which is the basis of the twist in the next cartoon example below.

2) The Copy is Devalued

Perhaps the best way to devalue a copy is to compare it with another copy of the same original, and then demonstrate some palpable advantage that the latter has over the former. This comparison can be used to demean the value of the first copy (whilst probably increasing the value of the latter). So we have to find an example of an original that has at least two copies that are of a qualitatively different to each other. This is not so hard to do: any toyshop will have different versions of the same basic car original on its shelves, and any art gallery will have different versions of painting of the same still life or model.

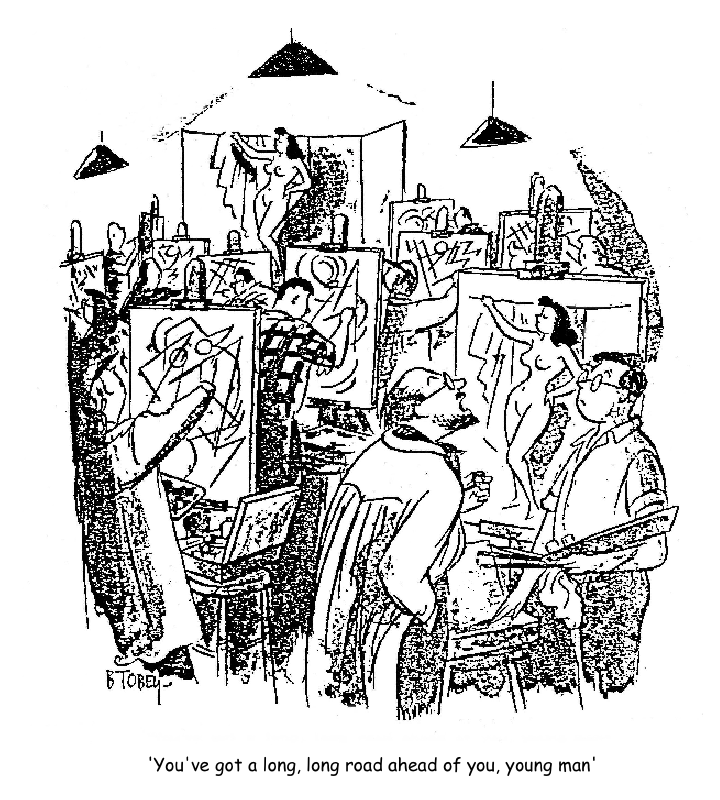

To wit, the following cartoon comes from a wonderful book published by the Tate Gallery in London called ‘A Child Of Six Could Do It’. It is a comment on the modern art movement, which eschews the ancient craft of representation for the nobler and more creative purpose of ‘interpretation’. The comment in the caption works against what we would normally consider to be an excellent copy, in favour of one that is almost entirely at variance with the appearance of the original.

So, which of the two copies is being devalued here? The traditional likeness, or the modern abstract? At first sight, and given the comment made by the art teacher, it looks to be the traditional one. It seems that the young man has a ‘long, long road ahead’ of him, before he presumably attains true artistic worth. But then, this is tongue in cheek surely? Because to the viewer, the likeness of the traditional painting is worth far more than the straight line abstractions of the other students. Especially given the particular appeal of the subject matter. But no, the official message of the cartoon is that the rest of the class is on the right path, and it is only our hapless beginner who still seems to think that a painting is all about a good likeness. So which is it? The official view of the art teacher, which is that representational painting is not worth bothering about, or the view, stagemanaged by the cartoonist, which is that abstract art is a waste of time?

The two views may be finely balanced in theory, but in practice, the cartoon is clearly making fun of abstract art and its practitioners. Because ‘Art’, at least as far as humour is concerned, is merely a form of copy, and gets no higher than that. Meaning that its worth must be judged in terms of copying fidelity, which for a painting of a subject like the young lady, means getting a good likeness. So the copy that is being devalued here is the abstract painting, whilst the ‘slavish imitation’ as a modernist might call it, is just doing its job as a routine copy. Rather well of course, because it is an exact copy of the model – a sleight of hand easily achieved when both depictions are the work of the same cartoonist after all.

So whereas, in the case of the landscape or the moose devaluations, it is the original that is found lacking, here we see that it is a version of the copy that is found wanting. But there is a difference here. Because in the first case, the Original is devalued by comparison with its Copy, but in the second case, the Copy is devalued, not by comparison with its Original, but by comparison with its neighbouring Copy. Indeed it is hard to see how the Copy can be devalued by comparing it to its Original as it is a given in the O/C relationship that the Copy is the lesser of the two, so this is entirely understandable.

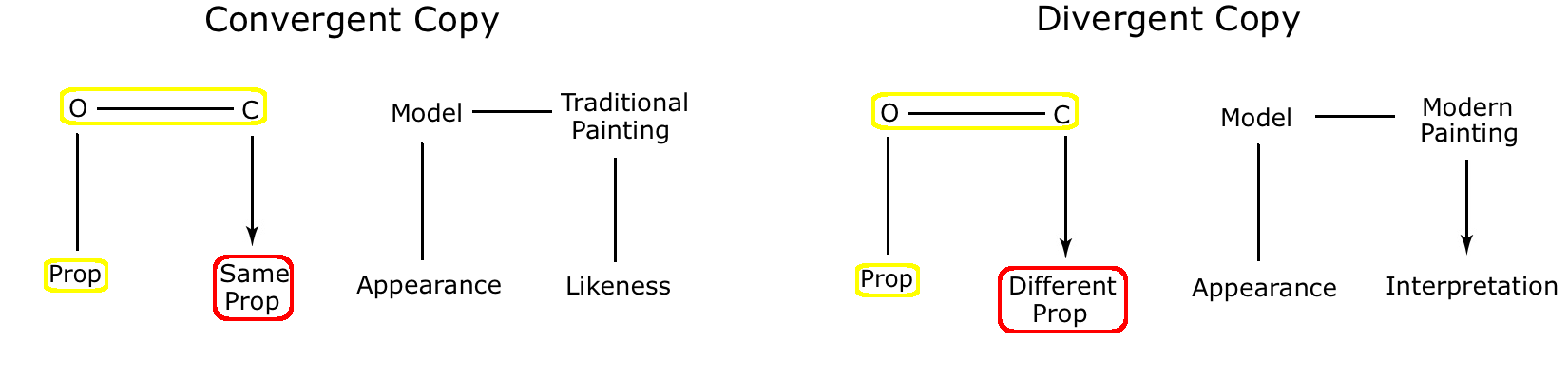

In the following diagram, we see the two copy applications that are the basis of this mockery of the world of art. Neither of these is a twist as such, although it is certainly true that the whole idea of a copy is ultimately a twist on reality if we go back to its inception, or to our first experience of copy duplicity. But in the first case, the copy imitates its original in time honoured fashion, to create a likeness. In the second, the copy departs from this literal view of the original to an interpretative role, where the copy looks less like the original.

Now imagine that instead of choosing a naked young lady as the original to be painted by the class, the cartoonist had chosen a still life, or even a landscape. What would such a comparison then yield in terms of the two copies? In particular, would we find the loss of likeness in the abstract works as unfortunate, or even as obvious? Surely we would not. On the other hand, the use of the curvy young subject of the naked girl is probably the best argument against the geometric straight lines of the other paintings humanly possible, simply because this is an image we prefer to see in its pure form. So we have two aspects to the debunking of the modern art movement here. Firstly, the abstract art is being pulled down by the reductionist act of evaluating it as a poor attempt at copy, and secondly, the choice of the particular subject matter ensures that few of us want to see it changed anyway.

The role of the O/C relationship in this debunking is primary. Copying fidelity, which is an important goal of most copy design, is championed through the calculated use of the one subject we all prefer to see ‘as is’. Meanwhile, the depiction of the alternative and abstract copy is about as far removed from this goal of good likeness as visually possible, so the dramatic contrast between the two copies is also convincing. In fact, the abstract painting is so far removed from its original that the cartoonist has had to insert two circles (left front) to ensure we recognise that it as a portrait of the young woman in the first place.

So is this a status reversal of the sort that we have come across before in the Think/Thwim and Slipper in the Oven cartoons? Or for that matter, in the two stories above, featuring the Map and the Moose costume? A reversal where the normal scheme of human evaluation or power is switched round so that the lowly rise above the high cast? Which in these examples ranges from elevating a small country above a large one, a wife above her husband, and a copy above its original? Well, there is a pattern here, and though it is showing an impressive range of application, applying to very different areas of evaluation, and using quite different levers to make the switch (eg puns or O/C), it does appear to be that the same general principle of ‘debunking’ is what we are looking at here.

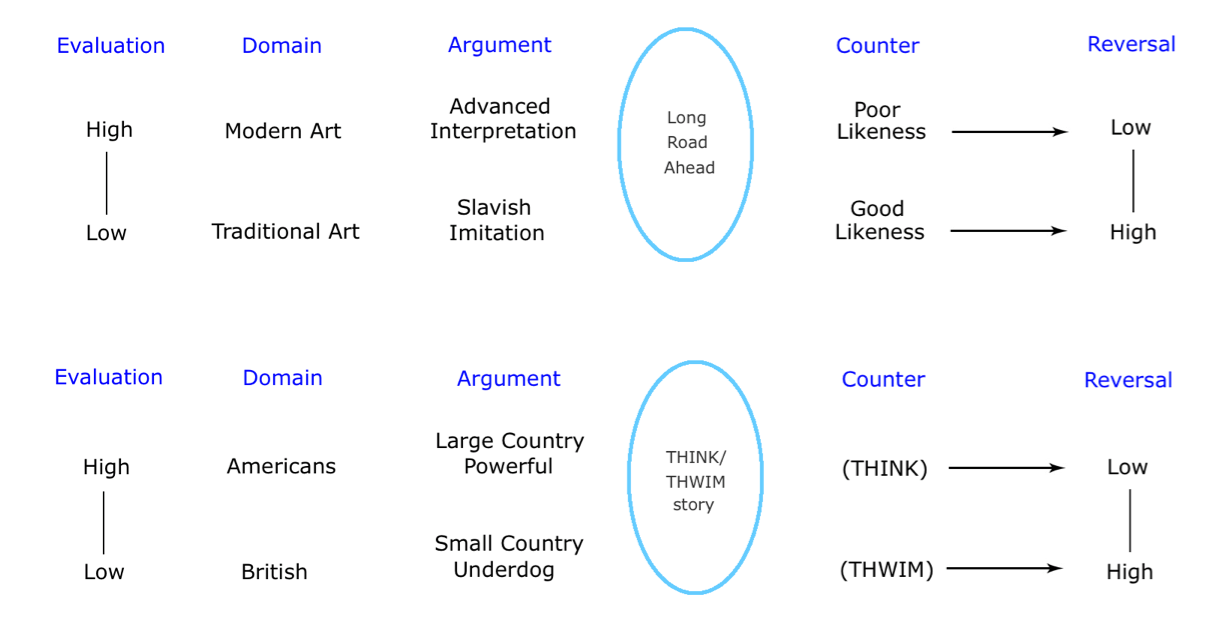

If we compare the debunking of the Americans, in the ’Think/Thwim’ example recounted in the section on the pun, with the ‘Long road ahead’ example using the O/C to make the status reversal in the cartoon above, we find some similarities. Notice that we are not only talking about a ‘Good Likeness’ in this first diagram as being the element of change, but that the choice of the original subject in question underlines the value of such a likeness to the maximum.

In each case, we are looking at a standard evaluation of an area of meaning that is presented explicitly (or implicitly) by the joke, and then given a counter to that normal expectation in the form of a cleverly contrived switcheroo, that turns the tables on the established view. In the ‘Long road ahead’ cartoon, the switcheroo uses copy logic and an appeal to our physical appreciation of the fair sex, whilst in the ‘Think/Thwim’ story, the switcheroo is based on the pun, and the concomitant change in the meaning of the IBM slogan. In each case the result is a reversal in the status of the two groups, but these groups are very different to each other (art movements versus computer corporations), though the switcheroos are not so different (both the pun and the copy are about duplicity).

On a different note: what is the basis for the departure of modern art from normal copying logic? Is it that the art world is just intrinsically the opposite of normal copy logic? Well, it may find slavish imitation too literal these days it is true, but it did not find the idea of a good likeness so unworthy in the past, and for many, the idea of a skilled and faithful representation of a subject is still an achievement. But copying fidelity is only one aspect of copy natural history because, as we know, copies are created to fulfil a number of human requirements, and one of these is indeed interpretation. So it is understandable that the art world emphasises this aspect of its work, when it is now so easy to use technology to achieve perfection in copying on a repeatable basis. But although copying fidelity is not the be-all and end-all of artistic representation any longer, it still takes unquestionable skill to get a good likeness, and it can still make an impressive image for all who see it.

In the past, on the other hand, art used to be very much more about copying fidelity, and these early copies were rare, so they were effectively the equivalent of twists, albeit in the name of religious experience, not humour. In fact, without the copying technology we now take for granted, an image that really caught the likeness of a person or landscape used to be tantamount to a powerful physical magic. Nor were the early copies diminished by the existence of duplicates. As John Berger observes in his splendid ‘Ways of Seeing’, ‘the uniqueness of every painting was once part of the uniqueness of the place where it resided’. But things are different now, awash as we are in a sea of photos and films that make the old art of catching a likeness much less valued than before. No wonder then that the emphasis in the art world has changed to new ways of seeing, and has moved from slavish imitation to the noble art of interpretation.

On a more general note, the gentle debunking of the modern art movement in this cartoon is in marked contrast to many of the cartoons so far considered, where the emphasis has been on the cerebral aspects of the copy world. For example, the idea of the maps being made to a progressively larger scale in the Lewis Carroll story is an exaggeration, based on O/C principles concerned with copy advantage, copying fidelity and negative properties, and clearly the result is a practical impossibility. This is in marked contrast to the evaluation in the ‘Long Road Ahead’ cartoon, which instead of twisting copy logic, makes a direct challenge to our human behaviour. Yes, it does achieve this at least partly by way of the O/C matter of copying fidelity it is true, but it is human behaviour in the firing line here, and not the ins and outs of copy logic. In this, it is comparable to the Bear cartoon, where the indignation of the bears at the folly and stupidity of their human captors is more compelling than the displacement and animation twists per se. Comparable, because in both cases, the cartoons have penetrated much deeper into human meaning than say the Landscape Running in the Rain, or even the General Montez cartoon.

The Equal Status Twist

3) The Original and the Copy are Equal

Notice that a third possibility for a change in status between an Original and its Copy exists, where the two components of the O/C relationship are compared, and shown to be equal. Now, given the well established primacy of the original, this equality could be seen as a simultaneous elevation of the copy and reduction of the original, with neither holding a superior position to the other. Which is indeed what we find in that classic example (below), already featured in the introduction to the nature of the O/C relationship.

This graphic comparison, where both the original sunset and its copy, the painting, are seen as the two sides of the same coin, is a really interesting one. Because although in literal terms, the sunset is genuinely real, and the painting is just a poor copy of this reality, the perception is that they are reflections of each other, and that neither is more real than the other. Nonetheless, there is an asymmetry here. So in the first frame, Nature is compared to Art (‘aint it just like a picture’) because sunsets are a popular choice of subject matter for artists, and that is how the real sunset is similar to a picture. But in the second frame, Art is compared to Nature because the copying fidelity of the painting is so high, it really does look like the real thing. So what looks like a genuine symmetry between the two realities of Physical Space and Social Space is an illusion to some extent. Nevertheless, it is surely the case that the net effect of the two frames compared is that both realities are a reflection of each other, and that both images therefore have equal standing. Which is not surprising because the virtual world within our heads is arguably more real to us than the supposedly real world outside, and together, these two realities form a complete picture of the human experience (an interaction symbolised by the ‘We are in the World, and the World is in our Heads’ cartoon in the introduction to this site).

Where to next?

Status reversal twists are interesting because they represent a very common source of humour, especially in those jokes that play off the different groups that we see represented by race, nationality, gender, class, religion and so on. But then, given that human meaning rests on an intricate system of values, it is not surprising that humour twists the evaluations that arise from this system, and the best way to do that is by reversing them. And it is certainly the aim of this analysis to reach much further into our human value systems further down the line. But at the moment, we are very much on the outskirts of such a project and goal, dealing with objects (copies) which although they are shaped by human purpose, yet they remain primarily physical. In fact, the next big step in this quest to use humour to map meaning is to cover a different relationship that is actually even further out, on the margins of social space. Because only after that will we understand enough about humour to look at a set of cartoons that are more centre stage to what most concerns us – in a place where evaluations and judgements are the norm rather than a shadowy presence in the background.

So this next big step is to investigate a very special place in the landscape of the imagination that I call the ‘Valley of Shadows and Reflections’. But that must wait until after we have stepped back, and swapped the zoom lens for the wide angle, in order to take a broader view at that part of the landscape that is the copy plateau.