Walking the Creative Path

What the Experts tell us

Cartoonists are much exercised by the challenge of joke creation, and this is hardly surprising. Firstly, it precedes the graphic challenge of presentation, because without the joke idea, there is nothing to present in a drawing, which means the joke idea always comes first. Secondly, how ever good our aspiring humorist may be at the drawing itself, if they can’t think up a good joke idea, then no cartoon editor will ever want to publish their work. We might go even further than this. Because however bad the drawing may look, as long as the joke idea is good, the cartoon stands a chance of being accepted. In fact, we have already gleaned as much from that past editor of Punch magazine, William Hewison, in a previous section on this site (‘a poor idea can never be redeemed by a marvellous drawing’). So the ability to create new jokes is what makes or breaks the successful cartoonist. Which probably explains why there are quite a number of cartoonists whose drawing style is frankly second rate, yet they are well represented in the cartoon literature due to their creative talent in thinking up new and amusing ideas.

The joke idea is indeed everything, and the need to think up new jokes is constantly at the forefront of every cartoonists mental focus, like a well formed habit and a half formed addiction. This has led, not surprisingly, to a great deal of written speculation on the whole difficult process of thinking up new material. This is why most large book shops stock a good number of offerings on ‘How to Become a Cartoonist’, many of them written by the best known members of their craft. Books that, predictably, show a great fascination with the basic problem of what it takes to create a joke. So, given the expertise of some of these humorists, surely the likelihood of gaining a valuable insight into the nature and creation of humour is high. What insight then, can we obtain from these experts in cartooning? In particular, what can they tell us about the actual pathway that leads to a new joke?

One of the best single line formulations about the process of cartoon creation comes from the British cartoonist, David Langdon:

‘My method of finding cartoon ideas is through what I can only call ‘controlled mind-wandering’.

‘Controlled mind-wandering’. These three words do indeed capture the paradoxical nature of the free, loosely structured, yet at the same time, goal oriented thinking that characterises the search for joke ideas. Because for those of us who have been through the testing experience of creating new cartoon ideas, these words offer a useful description of this extremely difficult task. In fact, ‘controlled mind-wandering’ is a formulation that very well describes the feeling of searching around for new joke ideas.

But do these same three words tell the aspirant creative spirit how to actually go about finding new jokes? No, they do not. They tell us how it feels to look for them, that is true, but they do not tell us how to find them, and that is the real goal here. Indeed, the idea of ‘controlled mind wandering’ does not even begin to scratch the surface of the blank and barren page that is the stark reality facing any would be humorist. But then maybe this formulation is not meant to be anything more than a comment on how it feels to venture along the creative path? Certainly it does not pretend to provide the explorer with a map of how to get there, nor what to do on arrival. So what do other cartoonists tell us that is more relevant to the practical problem of joke creation?

Ffolkes, a splendid cartoonist, particularly known in the UK for his wonderfully flowing female figures, has written a book entitled ‘Drawing Cartoons’. Which is a title well chosen, considering that of the 18 little sections to be found in the book, only one of these is, in fact, about the creation of new ideas. To be fair, this is typical of the many books written by cartoonists because, despite the very obvious desire to answer this age old question with something useful and practical, there really is a profound dearth of ideas about the challenge of joke creation in the literature. Anyway, in the one small chapter that is actually dedicated to joke creation, Ffolkes writes about the different headings that joke ideas fall under. Categories such as Matrimony, Exaggeration, Understatement, Reversal, Disaster, the Impossible, Recognition humour, the Saucy, Animals as People and vice versa. Which begins to be interesting. But then he fails to elaborate on how these categories might serve as the basis for the next step, to then take shape as real joke ideas. So the task of actually creating the new jokes is left entirely up to the reader. A reader who is now left standing, wondering how to ‘mind wander’ through matrimony, exaggeration and understatement on the way to successful joke creation.

Markow, an American cartoonist, is an author who seems at first sight to have slightly more to say about the matter in his ‘Drawing and Selling Cartoons’. But it turns out that his listing of subjects and themes, though wider, and certainly well illustrated with some well-chosen cartoons, is nevertheless leaving everything to the reader when it comes right down to it. For example, he writes: ‘Concentrate on one item for quite a while and you will find ideas developing.’ Right. Thank you Mr Markow. I’ll keep that invaluable insight in mind… presumably ‘for quite a while’.

The advice given to us by the specialists on the creation of the joke turns out to be a huge disappointment. True, they are experts at joke creation, but when it comes down to an objective understanding of what they do, they are no better than the rest of us. Yet strangely, the experts in objective thought and explanation, and who do have such a commitment, such as the social scientists and philosphers, actually seem to fare no better. In fact, some of what comes out of the social science literature turns out to be unintentionally funny in its own right, so heavily jargonised are its terms of reference. But rather surprisingly, I have failed to come across anything that is at all helpful when it comes down to the creative commitment of ‘how does this help me to actually create new jokes?’ And perhaps the real problem here is that both the creative and scientific sides lack the even handed approach that must necessarily arise from a commitment to both creation and analysis. Because, surely, the only way to solve the secret of the joke is to bring the two very different commitments of creation and explanation together – as one overall project. That is, we need to merge the approach and purpose of the humorist with the direction and commitment of the scientist. All of which means putting together an understanding of the joke that works in practice, because only then can the theory be tested, and only then can the practice be explained.

So why has this comprehensive and surely eminently worthy aim not been adopted by either the humorists or the social sciences? Well, the creators of humour generally hold that to dissect a joke is to kill it, and that there is no way to systematically account for the mystery of the intuitive process. Which is not to say they are not genuinely interested in the problem of joke creation. But it is to say that the humorists usually doubt that such a thing is feasible. This is understandable. After all, the creators of new humour do really know just how challenging their human subject is. This has to be so, given that they are wrestling with its intricacy and complexity on an everyday basis, and only rarely producing a real cracker in the process. So we can forgive the humorists for not wasting precious time on matters that may seem to them quite secondary to the problem of joke creation.

On the other side, many of the intellectual and scientific thinkers who have tried to analyse humour have failed to get very far either. To the extent that (to my knowledge) no useful workable definition of the joke has ever been proposed. So why might this be? Well it can hardly be because the joke is indefinable, nor that the creative process is inscrutable, because the sections above on the Original/Copy and Original/Image relationships clearly argue that this is not the case. Nor certainly is it because of a failure of commitment, or poor quality of mind. After all, many great thinkers have tried their luck with humour, and the literature on this subject goes back a long way. No, the reason for their failure is probably rather more mundane. Because, as we have already described, there are certain obstacles that stand in the way, and these make progress in the understanding of humour hard to achieve. So let us just quickly look at them again, but in the light of what we now know about joke logic through our discussion of the O/C and O/I relationships.

1) The search for a magic formula (usually based on the perceived attack pattern of the joke).

It is easy to fall foul of the idea that all jokes are based on say exaggeration or reversal, and therefore commit the error of the butterfly collector, and his sausage machine that we featured much earlier in this enquiry. But now, it seems, we can be more precise about the nature of this error. Because the real problem with such an approach is that much of the identity of the joke is tied up with the details of the particular relationship attacked. Which means that we must go where the joke leads, and become as familiar with the geography of its chosen target as we are with its own, singular, identity. In turn, this means that jokes differ just as widely as their subject matter, making the gap between the idea of a single joke formulation and the real living thing we call humour even greater. So even when we do have a model that seems to say something about the basic joke dynamics (such as our Relationship/Twist/Legit triplet), then we are still relying on an examination of the nature of the particular relationship and the subject source of the legit for a proper understanding of the particular joke under consideration.

2) The search for a general classification (usually based on the range of subjects attacked by the joke).

It is easy to get bogged down in the detailed and extensive range of joke natural history that is now available in the media of books, films, plays, stand up shows and animations. And just as we saw in the case of the butterfly collector in his gallery full of display cases (in What is the Secret Code…) it is easy to get lost in all this wealth of material. However, we are now in a position to say more about this particular problem. Because we only have to look at the range of domains within just the one relationship of O/C that we have studied, to see that there is a very wide spectrum of meaning represented there. Almost as if the tighter we make our focus, the wider it then becomes. For example, if we focus on a specific form of copy, such as Art, and then even further, onto two dimensional Art, then the more we look, the more we find that the paintings and drawings within that domain actually represent a vast range of areas within our human experience. All of which forces us to widen our focus, just when we thought we were doing the opposite, so that instead of zooming in to a greater specificity, we find ourselves widening things out again. Which means that we cannot escape the vast range of the landscape inside our heads just by narrowing down our focus. Is there, in fact, some good reason for this problem of focus? Well, because meaning has so many cross links, where everything is linked to everything else (reminiscent of the pyramidal neurons in the cortex), the multidimensional map of our virtual world is highly complex, and ever changing. As if, in biology, all the animals were cross linked so that the normal phylogenetic tree from spreading branches down to small and simpler origins was no longer a feasible proposition, making the origin of species a nightmare to work out, or for that matter to believe in altogether.

Having said that, it is also true that the relationship between an original and its copy and image has been identified to some appreciable extent, and that serioius progress has therefore been made. At least, we might argue, up to the point where the fundamental deficiency in our map of meaning has become a problem (the fundamental deficiency being that most of this map is blank). Furthermore, if the two approaches are combined, so that a single model of the joke is used to dissect all the jokes within a single identifiable subject area, then perhaps real progress can be made (though there are areas where this does not apply, as exemplified best by the pun). At which point, further progress can now be made, just as long as the analysis approaches the whole problem of understanding the joke by committing itself to the creative agenda elaborated below.

3) The acid test of the ‘Creative Option’ (usually considered to be an option open only to the humorists themselves).

This is not the road most taken by either side of the Arts/Science divide – for the very good reason that the creative option is the most challenging position to follow. However, the challenge does make for good science. For only by wrestling with reality do we really learn how reality behaves, and giving the material the chance to fight back, and reveal mistakes in understanding, is basic to the scientific dialogue we have with nature. But the relative difference between the approach of “Let’s explain humour”, and the actively creative approach of “Let’s make up a new joke”, is considerable. A shift we have already seen in the close consideration of a number of cartoons, where the emphasis has sometimes moved from the ‘what is there in this joke’, to the ‘yes, but how do we get there’ side of things. The underlying agenda being that if the ideas that come out of our analysis are any good, then they should help us to create new jokes, and yes, ultimately to provide the insight to create algo’s that then go even further in that direction. So, this is the acid-test. Do our ideas about humour work in practice, and are they powerful enough to create examples, as well as to explain them? And perhaps it is this test, more than any other challenge presented by humour, that has stopped real progress being made up to this point.

The task now facing this enquiry therefore reaches a new and interesting level. Because it is time to test the insights drawn from the analysis of copy and image logic, and to do this, we must use these supposedly useful insights in the creation of new joke ideas.

One Way To Get There

Let us imagine what the printout for the creation of a joke idea might look like. It would certainly consist of a series of steps, and at each step, choices will have to be made. And in principle, the pool from which these choices will be drawn is as wide, and as deep, as the sum total of all human meaning. In practice however, its limits will be tighter than this, because both the creator and the audience are bound to be limited in their experience to a particular culture and period for example. There are also the limits set by the medium of the cartoon, where visual matters take priority, and by the caption, where space is very short indeed. But even so, and within these parameters, the pool of meaning from which the choices are to be made is very very large indeed.

In abstract then, the reader will see that this series of steps towards the creation of a cartoon consists of a series of ‘Decision levels’, ‘Options’, and ‘Choices’, and that together, these go from the general to the particular, through a series of choices, all of which are vital if the creative path is to be fulfilled. The keen reader will spot right away that these three terms are more or less synonymous, but as we shall see, they make sense once applied to the more complicated listing of the sort we shall look at below.

The Decision Level is the first element in each stage (and is shown in BLACK), and it comes in the form of a question. In this case, two familiar examples would be ‘Which Relationship?’ and ‘Which Twist?’ In each case, this is then followed by a list of Options (in BLUE). For example, the ‘Which Relationship?’ decision level would lead to an option list of possible relationships, and the ‘Which Twist?’ level would lead to an option list of all the possible twists opened up by our choice of a particular relationship. Finally, the third level is the actual choice we make every time we are presented with a list of options. So the specific choice (shown in RED ) for a particular relationship might be ‘Original/Copy’, and the choice for a particular twist might be ‘Imitation’, and then the choice for a particular attack pattern might be ‘Original like its Copy’. But all of this is much easier to appreciate in the following example, where we use this format in the two line pattern shown:

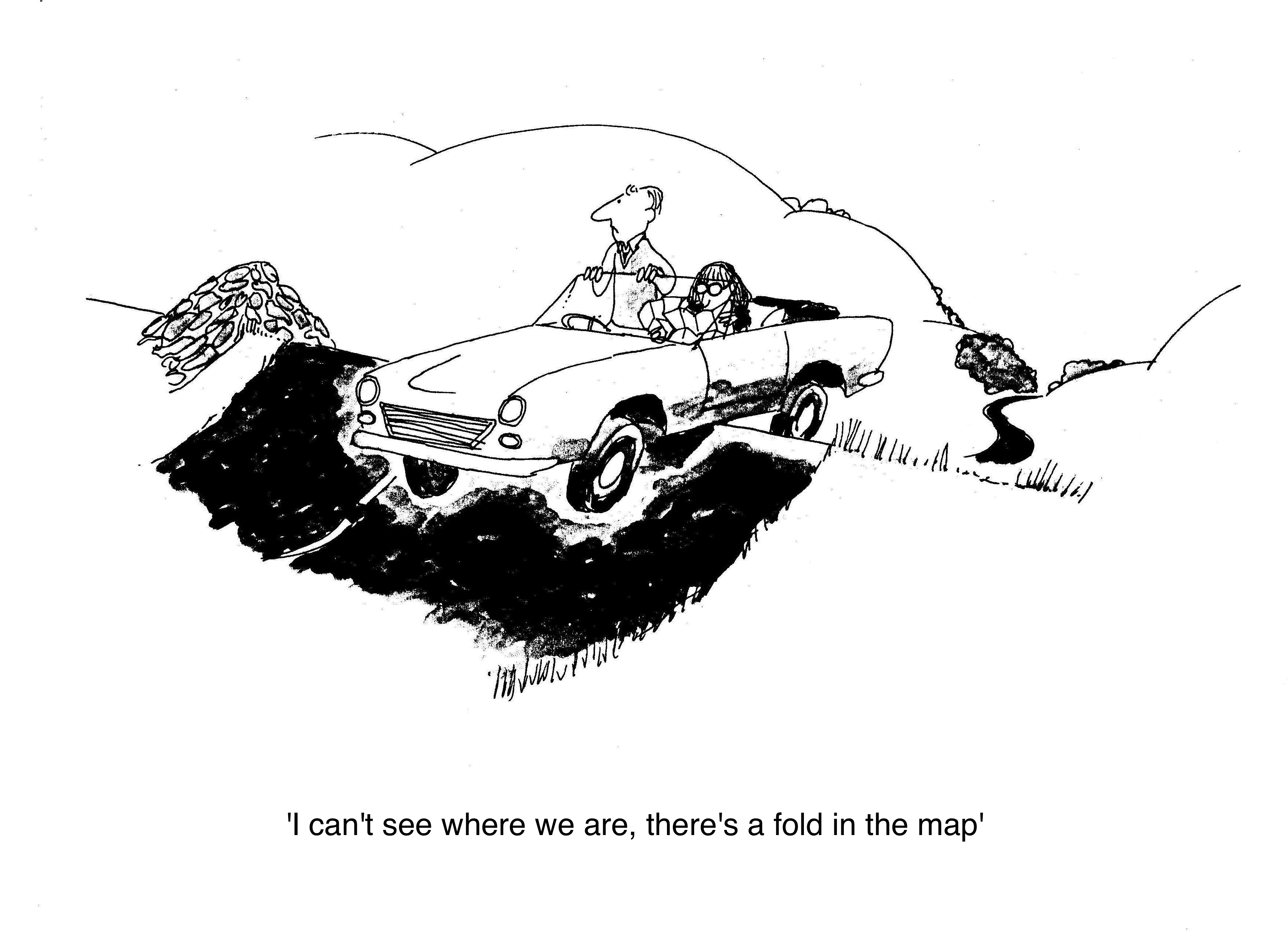

So now, we are going to go through an actual example of the series of steps that lead to a joke idea. This is the first one that these writing ever prompted, and it works out quite well. The cartoon that derives from this idea is not one of those resplendent specimens that were referred to in the whole issue about a gallery of the best cartoons versus a representative collection of cartoons (we used the metaphor of the best butterflies versus an actual collection of specimens, where many of the examples are nowhere near as dramatic as the ones in a specially chosen display case). But it is easily recognisable as an average cartoon, and the steps that we take to get to it are also perfectly reasonable and useful, although there will be a critical list of the shortcomings of this list further on.

PRESENTATION? Practical Joke/Live Sketch/Verbal/Visual…

Visual – single frame (versus Multi-Framer, Animated Cartoon, Film Sketch…)

RELATIONSHIP? Original/Image, Adult/Kid, Animal/Man, Original/Copy…

Original/Copy.

TWIST? Imitation/Displacement/Sidestep/Confusion…

Imitation.

ATTACK PATTERN? C like O, C like neg props of O, O like C…

O like C.

COPY DOMAIN? Toys/Entertainment/Geographic/Scientific/Artistic/Religious…

Geographic – 2D.

COPY MEMBER? Solar system/Moon/Earth/Sea/Land/Town/Building…

Land – Map – Rural.

COPY PROPERTY? Paper/edge/fold/scale/size/symbols…

Fold.

ORIGINAL? Country/Topography/Natural Feature…

Rural landscape with road.

IMITATED PROPERTY REFERENCE? Lateral pleat or Vertical rising/trench…

Rising fold runs through road.

COPY REFERENCE? Hiker or Car/Bus/Lorry Driver – looking at, or holding a Map…

Map in car.

VISUAL COPY PROPERTY REFERENCE? There’s a Fold in the Map, so there must be one in the landscape

Picture of the Fold in the Landscape

VERBAL COPY PROPERTY REFERENCE? Straight Caption, or Caption of Speech from driver, or passenger…

‘There’s a Fold in the Map’

VISUAL DRAMATISATION OF IMPOSED PROPERTY? Car stopped by/stuck on/bouncing off/ the fold…

Car stuck on ‘fold’ + Passenger looking at folded map

VERBAL DRAMATISATION OF IMPOSED PROPERTY? Explicit link: “I told you there was a fold in the map…”

Implicit link: “I don’t know where we are; there’s a fold in the map”.

“I can’t see where we are; there’s a fold in the map.”

At which point, our cartoonist must step in to wrestle with the final details of the visual presentation.

Another Way to Get There?