How To Twist Shadows and Reflections

In which we describe the Original/Image relationship, and how it can be twisted to make jokes, with particular reference to breaks in Visual Correspondence

Images are like copies because they imitate their originals. That is, both shadows and reflections faithfully reproduce their casting objects (albeit it in two dimensions, not three) provided always that the right physical conditions are in place. So it is no surprise to find that there are a good number of twists on imitation in the cartoon literature, just as there are with the copy relationship. But there is an important difference in the scale of this imitation. A difference that comes down to the physical fact that reflections and shadows pursue the imitation of their original casting objects in ‘real time’. That is, the image is tied to its original by physical conditions that oblige it to slavishly follow its original wherever it goes. Slavishly, that is, but not sluggishly. Because the ‘Visual Correspondence’ between an original and its image occurs at the speed of light. Which means that the form of imitation we are looking at here is on a dramatically different scale to that of the imitation between an original and its copy. Different because the image is in a state of instant and continuous update in relation to its original. All of which amounts to an unsurpassed loyalty of the image to its casting object.

It is this natural imitation that humour then takes ‘just a little bit further’, in a line that seems continuous, but is actually at variance with that of the physical logic underlying visual correspondence. For example, an image may be made to behave more like its casting object than is usual or, contrariwise, the casting object can be made to take on one of the properties of its shadow or reflection. In other words, further properties can be transferred in both directions to create the twist, and all this based on the logic and legitimacy of the established ‘imitation’ that exists within and between each pairing. That then is the basis of the imitation twist between the image and its original.

Now, whereas copies exist to imitate their originals, and are made to do so through human manipulation, images do not exist to imitate their originals. Instead, they merely exist full stop. That is, there is no purpose involved in this imitation. But the net result is the same insofar as it creates a world of doppelgangers, and just like those other duplicates, such as puns and copies, these certainly exercise the humorous imagination. Indeed, in some ways, the image is rather better at this ‘job’ of imitation than its cousin, the copy, because it maintains this semblance to its original with greater fidelity, and in real time, changing when its casting object changes, and without the slightest pause. It is true that modern recording technology does allow some kinds of copy making to do the same, notably in the film making world, but images need no such intervention, and do it right across the known universe.

But in this context of the imitation twist, the big difference between the copy and the image is that the shadow or reflection is lost without its original. So if the object disappears, the shadow or reflection disappears too. Which is to say that the image can only exist in direct proximity to its original, whereas the copy exists independently of its original (this being part of its primary purpose). The copy therefore has its own separate physical identity, unattached to its ‘casting object’, but the image relies entirely on its objects presence for its continued existence. And it is precisely this reliance that we refer to as the ‘Visual Correspondence’ between the casting object, and its shadow or reflection.

Twists on visual correspondence generally blame the image. This is because it is the casting object, along with the light and surface conditions, that ‘calls the shots’. After all, the object exists entirely without reference to its image, and therefore can and does change entirely without reference to any of the transient and fleeting forms that may ape its behaviour. It follows therefore, that if there is any breakdown in the visual correspondence between the two, it must be the image that is to blame. A fact which becomes clear when we imagine the following scene.

Imagine a figure standing by a lake casting a reflection on the water. If the figure changes in some way, and the image fails to, the image is clearly at fault – it is obstinately holding position when it should be following its master. This is a law of nature: images do not and cannot move on their own. Objects and human figures do, but their shadows and reflections do not. So naturally if the figure goes away and the image stays, the image is still at fault. And if the figure is replaced by a different one, and the image stays the same, the image is still at fault even though we might want to appreciate its obstinate loyalty to its erstwhile original. The bottom line being that whilst figures are independent and animate entities that pay no attention to their shadows or reflections, their images are totally dependent slaves, doomed by the dictates of visual correspondence to follow every whim of their casting objects, luminous creator, and physical canvas.

What happens if we switch the situation around though? So that now the image changes despite the fact that its original continues to sit there without moving. Well again, it is the image breaking the physical rules. We might say that, in this case, the image is being ‘fickle’, because it is changing without the permission of its original. Note that it is NOT the original that is being obstinate by staying there without changing, because that is a natural state for objects to assume. And if, for example, the image disappears altogether (with the physical conditions a constant), and we see that the original is still there, then the mismatch is still the fault of the image. Again, the same applies to the replacement of the image by another entirely different image. Because in all of these cases, it is not the original that is being obstinate, it is the image that is being fickle.

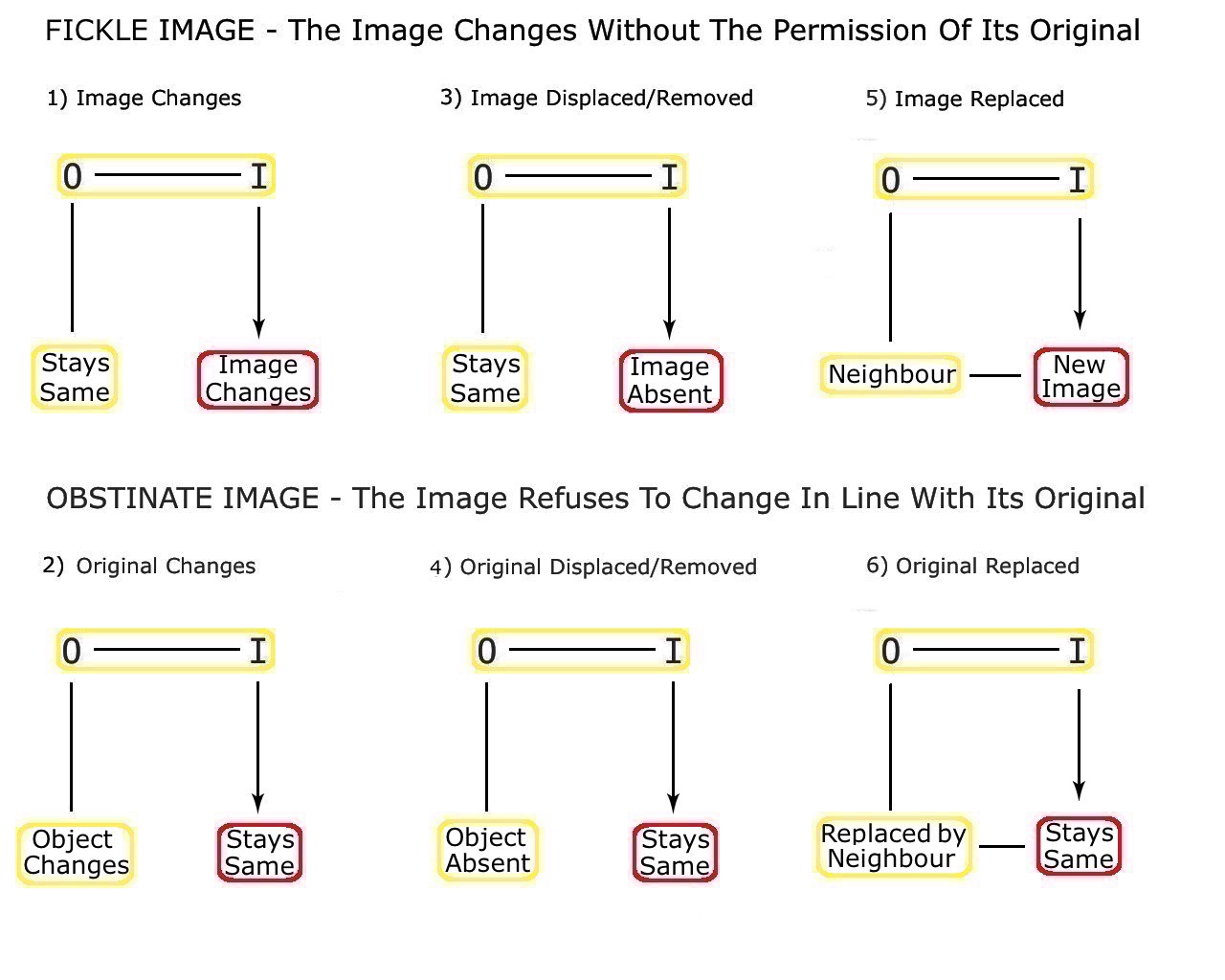

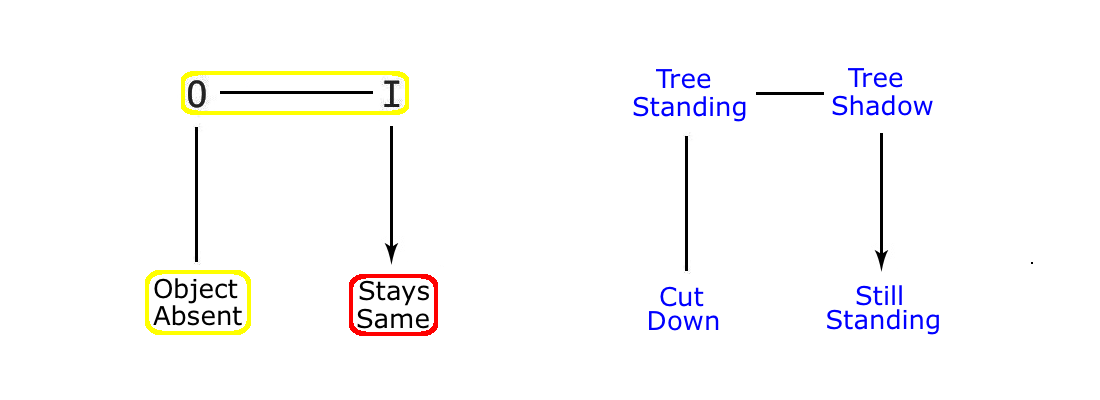

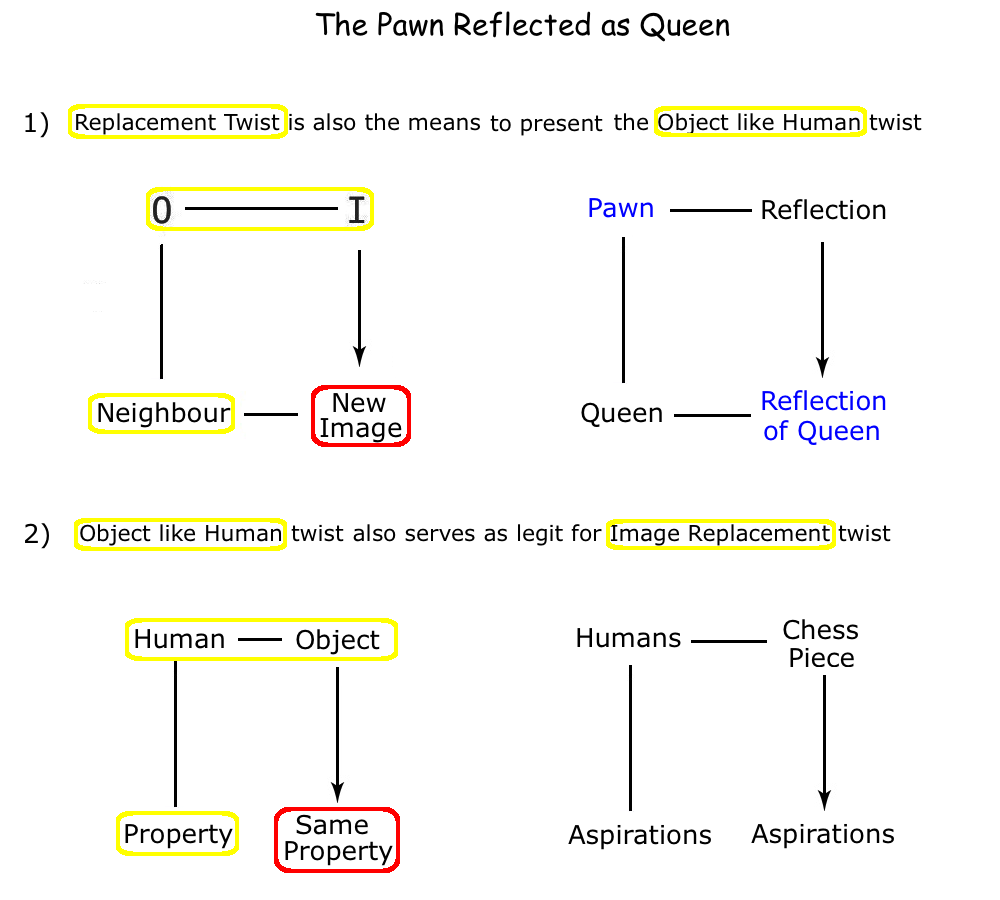

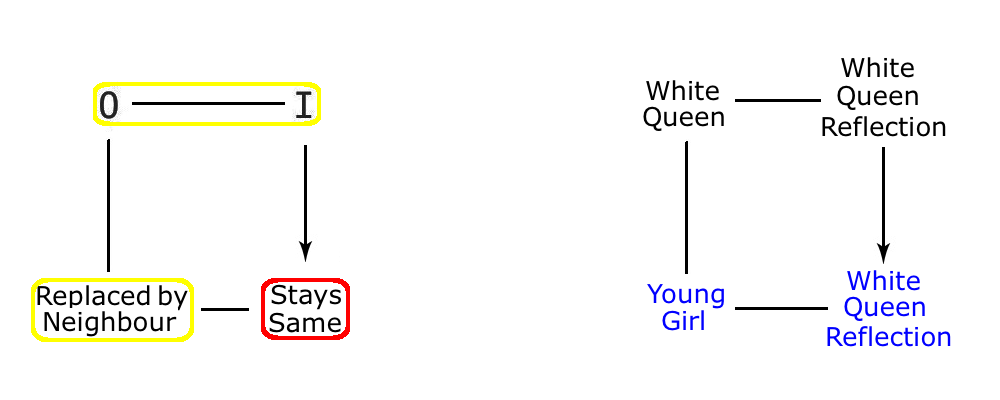

So, in twists on visual correspondence, there are three twists where the image is being ‘Obstinate’, by refusing to change, disappear or be replaced by another image, whilst its original shows no change. And there are three other twists where the image is being ‘Fickle’, this time proactively changing, disappearing or even replacing itself, whilst all the time, its original sits there without changing at all. (Another way of looking at this would be to say that the image falls behind or goes ahead of the casting object, but the terms obstinate and fickle serve our purpose well enough). All of this will become much clearer once we consider the cartoon examples that explore these various twists, but let us ask a further question here.

Are there any cases where the image is not at fault – and where it is the casting object that is to ‘blame’? Well, surely the image is not at fault if the imitation is totally the other way round, this being where the original takes on a property of the image? Because in this case, it is not the rules of optics that are being challenged, but rather the physical properties of the original that are being played around with. So for example, if the casting object copies one of the physical properties of its shadow or reflection, then this is not something we can lay at the foot of its image. Now normally such a change in the casting object – let’s imagine it ripples like its reflection in the lake before it – would then be reflected by its image, and the twist would be lost. So does the cartoonist get round that problem? Well, as we shall see further on, there are ways of getting around this, with the result that it really is possible to create cases of the O/I twist that fall squarely on the original. But as this takes us outside the category of visual correspondence, we will have to wait until the next section for further illumination.

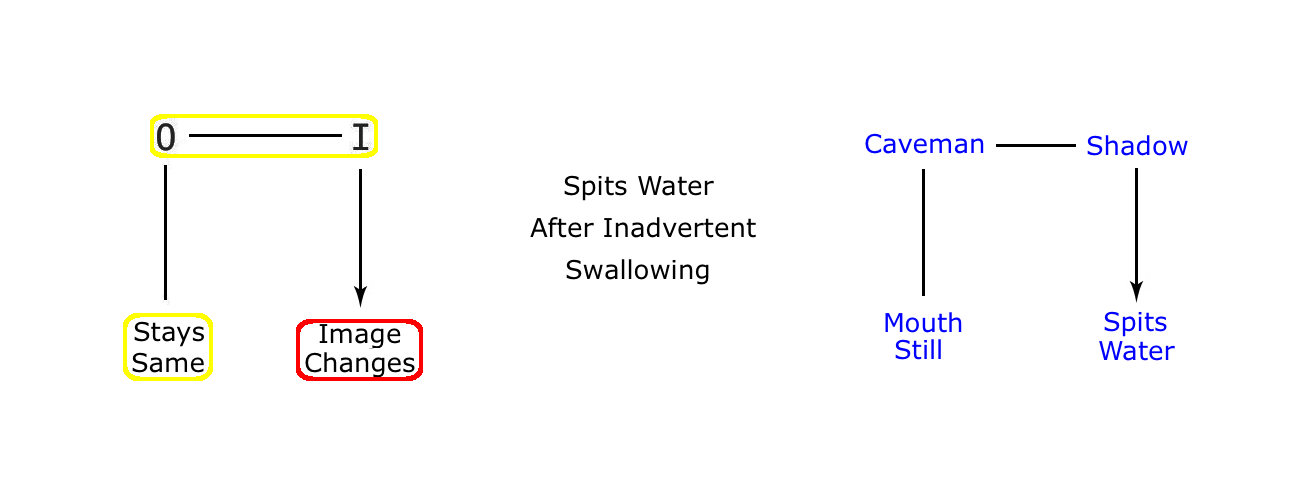

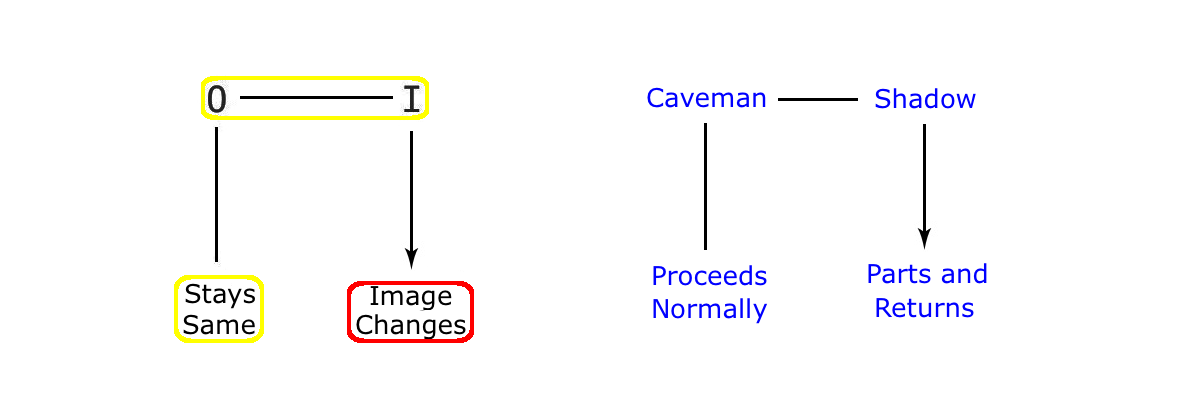

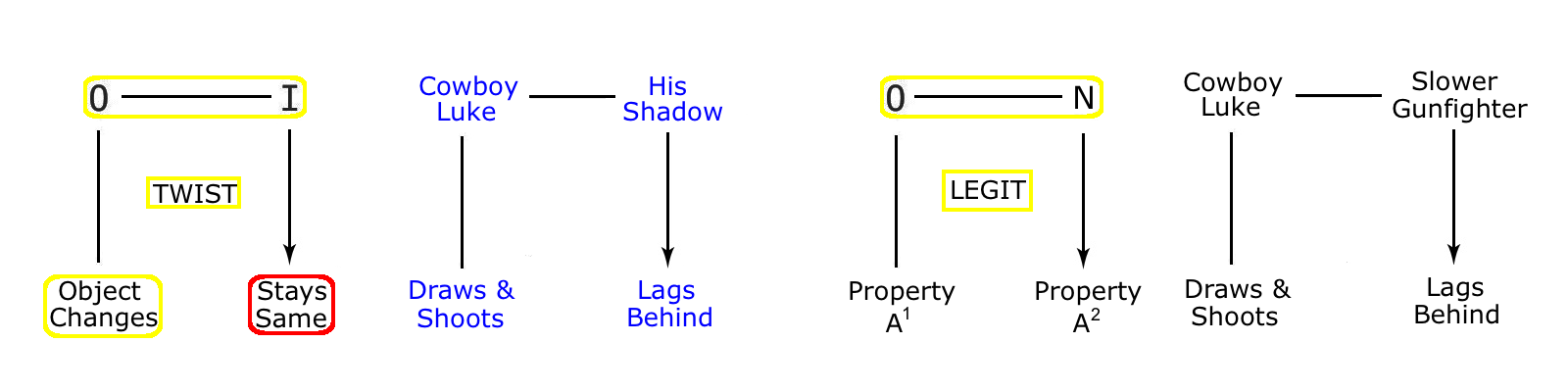

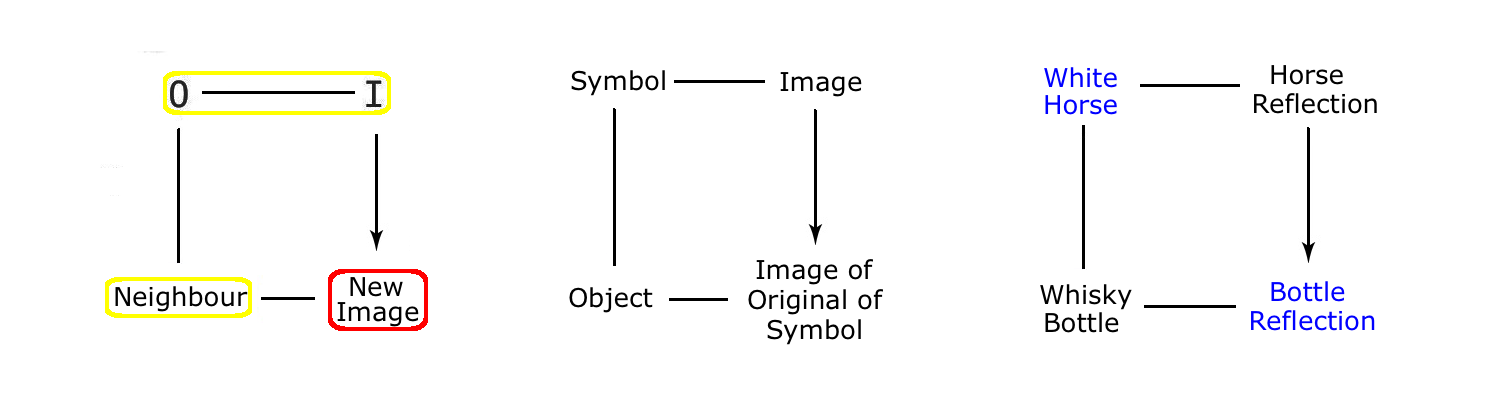

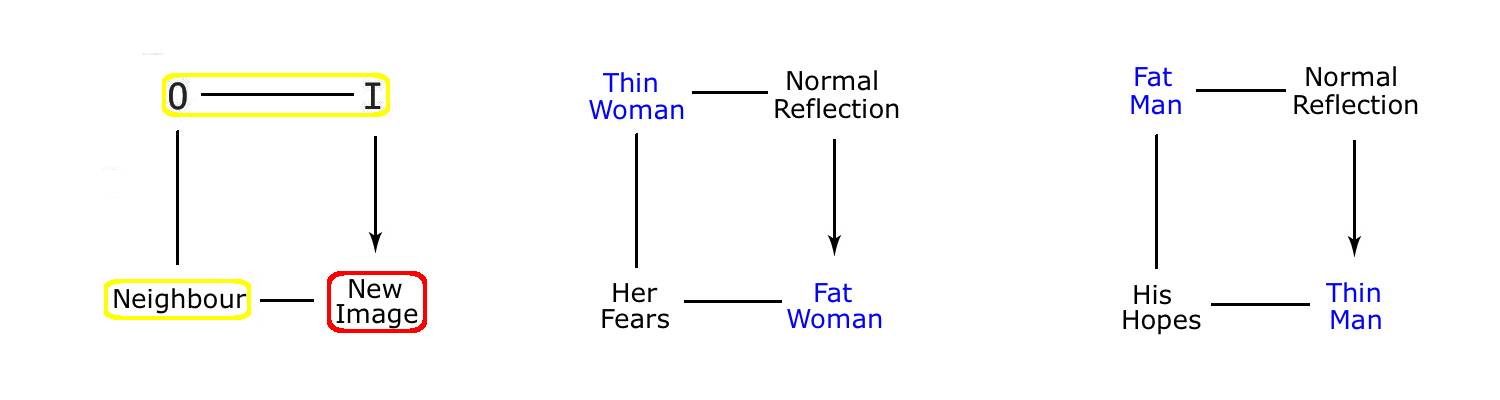

Meanwhile, here is a diagrammatic synopsis of the six possible twists on visual correspondence that obtain between an original, and its image.

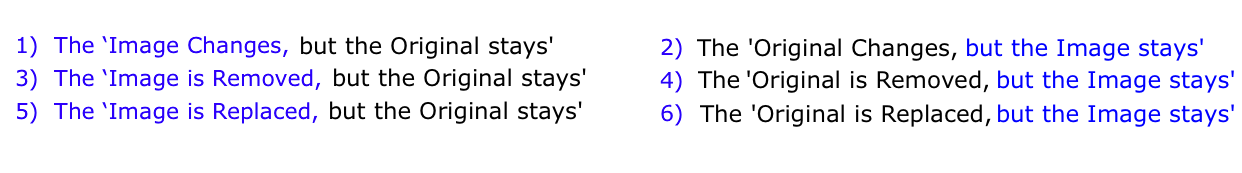

We can refer to these six twists more fully as

So, the ‘Fickle Image’ is where the Image plays around, but the Original stays the same, and the ‘Obstinate Image’ is where the Image stays the same, although its Original has changed in some way. So, in either set of alternatives, it is the image that is responsible for the mismatch, and not the original. The text in blue draws attention to the action of the twist and the ‘misbehaviour’ of the image. The text in black shows the original standing still, or being changed in some way – but in a way that does not challenge the laws of physics and is indeed entirely normal or at least plausible.

The best way to understand these six twist types is to look at some cartoon examples, so here they are, in the same order as the diagrams, with the first pair being The Image Changes/The Original Stays the Same. Meaning that the image is being fickle.

1) The ‘Image Changes, but the Original Stays’ Twist

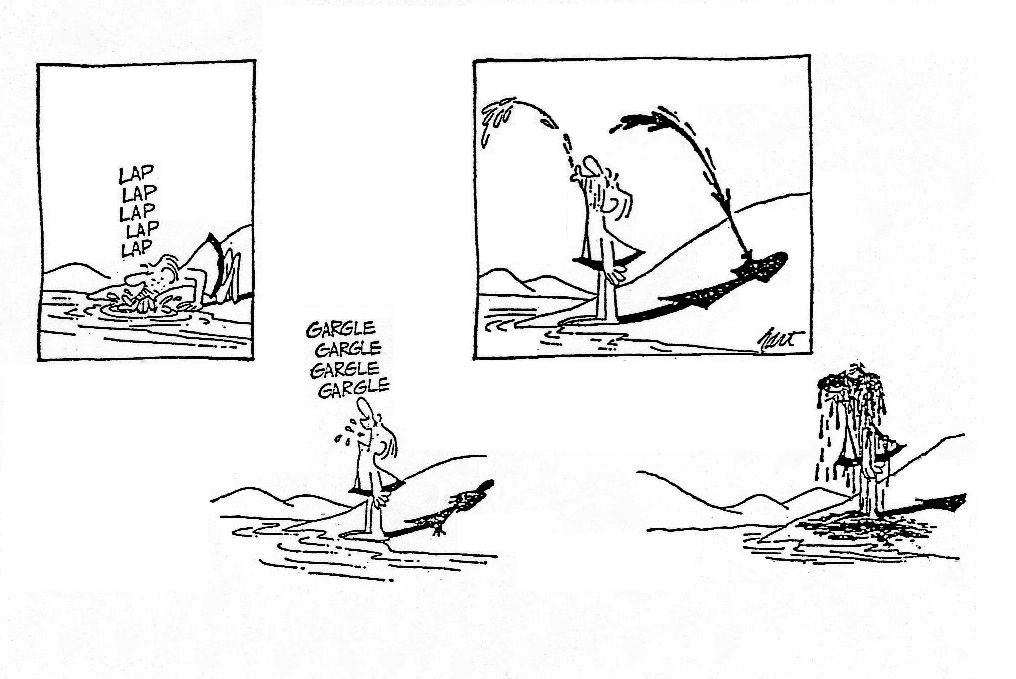

Shadows and reflections are no more the exact clones of their casting objects than are copies exact clones of their originals. So there are always plenty of differences for humour in the O/I relationship to exploit, especially given the vastly greater range of image natural history (most objects do not have a copy, but every object has an image). For example, in the following cartoon, the shadow has only a few physical properties of its own, but because its original casting object is property rich, there is plenty for the humorist to play with. Not to mention the fact that when the casting object is also animate and in this case also a human being, like the caveman in this cartoon, there is even more potential for the humorous imagination to create a twist.

Shadows are remarkable in the way that they follow both the shape and the movement of their original. So it is relatively easy for the cartoonist to transfer an additional property to the man’s shadow without stretching our credulity that much. All of which is familiar territory – it is easy to gain legitimacy with imitation twists if the relationship already involves a marked level of imitation. Marked in this case because the shadow is not just copying the shape of the man, but moves exactly like him too. So the extra little bit of imitation is just taking things a little further – and, as we have seen already in the analysis of the O/C relationship, exaggeration points in the same direction as the normal logic of the relationship (whilst denial reverses that direction).

However, images do not enjoy the luxury of the legit that we saw for example in the ‘It’s something new in a wig’ cartoon. So images, under the aegis of the cartoonist, cannot lay claim to the drive for greater authenticity that we see in the world of salesmanship and commerce. No cartoonist can claim, for example, that a shadow or reflection acts even more like a human because it wants to, or that greater copying fidelity should now stretch to its having more substantial properties such as being a material entity. We might say that images are different to copies because they belong quite outside our normal human logic and meaning, and they are therefore ‘hard to tame’. So images are wild phenomena that are quite unlike those humanly designed and created slaves of human purpose that are now so familiar to us as copies. (If copies are like domestic dogs, then images are like extremely feral cats).

However, although images are wild, they are far better at imitation than most of our humanly contrived copies, showing a vital and energetic fidelity to their originals that puts most copies to shame. Thus reflections mirror the details of their casting objects in great detail, and do so in real time, without effort or cost. Whilst although shadows lack detail, they make up for it by moving over a surface that is much freer than the confines of a mirror or lake, and this is also the same surface we live on ourselves, all of which helps to make the shadow an honorary and animate being in its own right.

In this respect, I would venture the following principle. Namely, that when we look at ourselves in a mirror, we are primarily interested in what we see of the original, rather than thinking too much about the phenomenon of the image as an entity in its own right. But when we look at a shadow, we are much more interested in looking at the way the shadow works, and we ignore the visual feedback it is giving us about our appearance (because the level of detail it offers is minimal). So when we see a shadow, we really see the shadow as an entity, but when we see a reflection, we use that to look at what is reflected, rather than seeing it as an entity in its own right. Which suggests that shadows are more appealing to our imaginations than the more literal, and additionally rather confined, world of reflections.

Here then is the printout from our semantic fingerprint machine for the caveman cartoon above.

The shadow has jumped out of its passive role as follower, and started to imitate its master. But not directly: because if its owner had spat out water at the same time, it would just have been another case of normal visual correspondence between an image and its original. So there has to be a mismatch, where the caveman walks on without doing anything remarkable. And after all, he has not been dragged through a stream in the horizontal position so there is no need for him to spit out water. (And if he did, then we would be puzzled by his behaviour, and not that of his reflection).

What the shadow does, by taking on this human property, is to challenge the norms of the physical world by suddenly turning into a material entity. But we may not be that impressed by this change. Because frankly, we are used to seeing human behaviour in all types of things, and especially when that thing has a human shape and movement like this shadow does. However, in this case, a property of the human original, which is that we might spit out inadvertently swallowed water if dragged through a stream, has then been foisted onto the hapless shadow, so we feel empathy for the shadow, and its sad position on the ground. Which means that its quiet and uncomplaining reaction to its fate, totally unheeded by its owner, takes us deep into the logic of Social Space, where the underdog is, as so often, the fulcrum for amusement. Making this an interesting fate for what, after all, is an entity that belongs to the dark depths of Physical Space. But then, anything that gets pulled into SS from PS will then enjoy this sudden trip from one extreme to the other, albeit to a greater or a lesser extent. Though, as we shall see when we pursue other cartoon examples, some images only get pulled in a little way whilst others, like this shadow here, end up deep inside human meaning.

So although this cartoon is based on a twist on visual correspondence, where the image takes on a property of its original, the result is also a twist on the relationship between a notional slave and its master. A relationship that involves a responce from the slave that is probably too understated to seem like much of a status reversal, yet anthropomorphic enough to be an ‘Image as Human’ twist, which is what happens when human shadows are made to show independent action (indeed, even just a normal shadow of a person can seem like a separate being in certain circumstances). The example is not then a pure form, where the twist is solely on the natural physical fact of visual correspondence. But at least we now have a start, with an example of an image taking on a property of its original. And the understated presentation of this status reversal twist give us a sharp contrast to the cartoon below, which is by the same cartoonist.

It is quite unusual to find two versions of a joke with the same relationship (O/I), domain (reflection), membership (human figure), aspect (property), twist (imitation) and attack pattern (transfer of property to image). And it is also of great interest – because we can compare them (almost as if this were the semantic equivalent of a twin study).

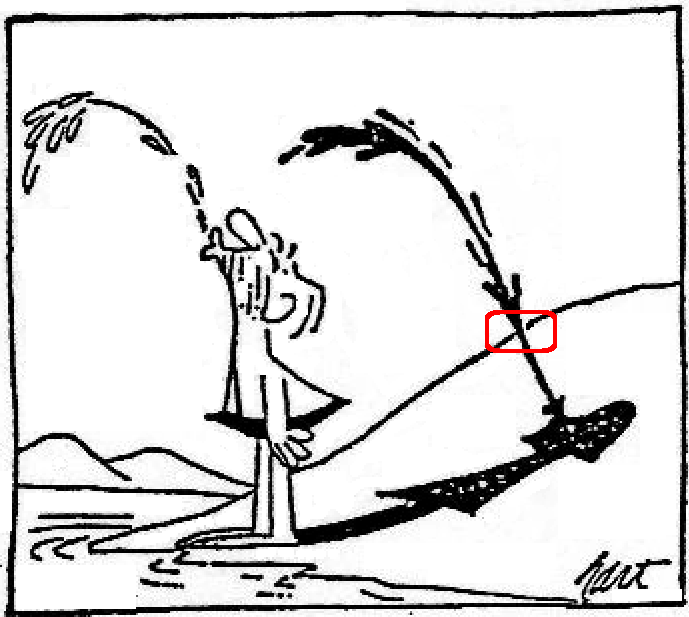

At first sight, this second cartoon does not seem to be an example where the original stays the same, and the image changes, because our caveman is spitting at the same time as the shadow, which is simply an example of normal visual correspondence. That is, there is no break between the two elements, and so there is no twist. Yet we know there is a twist here, because the shadow turns from its insubstantial state into a jet of water, and drenches its owner. But if we look closely at frame three, we see the join between standard visual correspondence, and something altogether different.

In frame two, we see the shadow doing its normal job of following its owner on the ground. Then, quite suddenly, in frame three, the shadow shoots up in the air, and crosses a critical boundary. Critical in that it is the boundary that marks the difference between the real world outside, and the virtual world inside our heads. Yes, we know that a shadow cannot manifest visually in thin air (let alone as a spout of real water), but the join between the two realities is nicely done. So the shadow spout passes this critical boundary line, exactly where the hill becomes the air, in complete synchrony with its casting spout of water, and carries on as if nothing untoward had occurred. And who is looking anyway? After all, the two together; the real spout of water, and its shadow, both leaping up into the air in complete visual symmetry, are so complete we feel no need to scrutinise the image for details. Rather, our attention is aimed at the end result of the twist, where the caveman gets drenched by his, up to this point, unassuming and hapless shadow. A dramatic denouement that conceals the subtle ‘crossing of the line’ between the different realities of Physical Space and Social Space, where the sleight of pen that is the hand of humour is invisible for that all-important moment of the joke.

But surely, if the shadow mirrors the real jet of water made by the caveman, then this is visual correspondence? Because it certainly looks all present and correct as far as the two silhouettes are concerned. But then there is the little matter of shadows manifesting in thin air, and falling down as water… Which is not the correct behaviour to expect of any shadow, anytime, and anywhere in the known universe. Because what looks like visual correspondence, and what is indeed intended to look like visual correspondence, is in fact fabricated to conceal the fact that the link between the original and its image has been broken. Broken at the point where the image suddenly starts imitating the arc, shape and substance of the real jet of water, before it then collapses upon its unsuspecting master.

So this turns out to be a really tricky twist to assess in this cartoon. Because it seems to pursue visual correspondence, come what may, and right to the end, whilst in fact breaking it early on, and almost at the start of its own visual conception. It is the duplicity of the shadow, as it seems to trace its arc in synchrony with it casting jet from the caveman, that is so perfect here, because it fools us for the vital moment the cartoon needs to then throw us into frame four, where there is a surprise. Suddenly, the shadow turns into a real jet of water, just like its casting original. Not only that, but this jet then twists the normal relationship between the caveman and his supposedly subservient image in what is a status reversal, where the leading figure gets drenched by his shadowy slave. All of which makes this cartoon very interesting because the image changes, but uses one of these changes (shadow in air) to conceal its changes until the last frame, where all at once, we see we were fooled, like the caveman, and the shadow wins the day.

Which is the better of the two cartoons? (This is a good way of pointing at how meaningful each of the cartoons appears, and will vary according to viewpoint). For example, we might agree that neither of these cartoons are world beating ideas, but the second version somehow comes across as the better one. Perhaps because there is some emotional content in the last frame, where the owner of the shadow is the victim of a practical joke, and is understandably peeved. Contrariwise, it can be argued that there is emotional content in the previous cartoon. The poor shadow gets dragged through a stream, but displays a quiet dignity, and merely spits the water out when back on dry land, in sharp contrast to the latter cartoon, where it drenches its owner, really for no obvious reason at all. Well, we might say that the former is sardonic whilst the latter is slapstick.

Notice that the clever artifice of the second cartoon is absent in the first example, where the shadow simply spits out a spout of actual water, with no attempt to hide the sudden change from shadowy immateriality to liquid spout. And we can imagine that if the spout coming out of the shadow had stayed as a black shadow, then the joke would lose some clarity.

There are two important differences between these two cartoons.

The first is about how the shadow spout is managed:

Cartoon 1: Immediate change from black shadow to white water.

Cartoon 2: Change hidden through the symmetry of the arc/shape, and shadow also stays black until very last moment.

The second is about how the shadow relates to its owner:

Cartoon 1: The shadow makes a quiet but dignified protest.

Cartoon 2: The shadow openly attacks its master, and without obvious provocation.

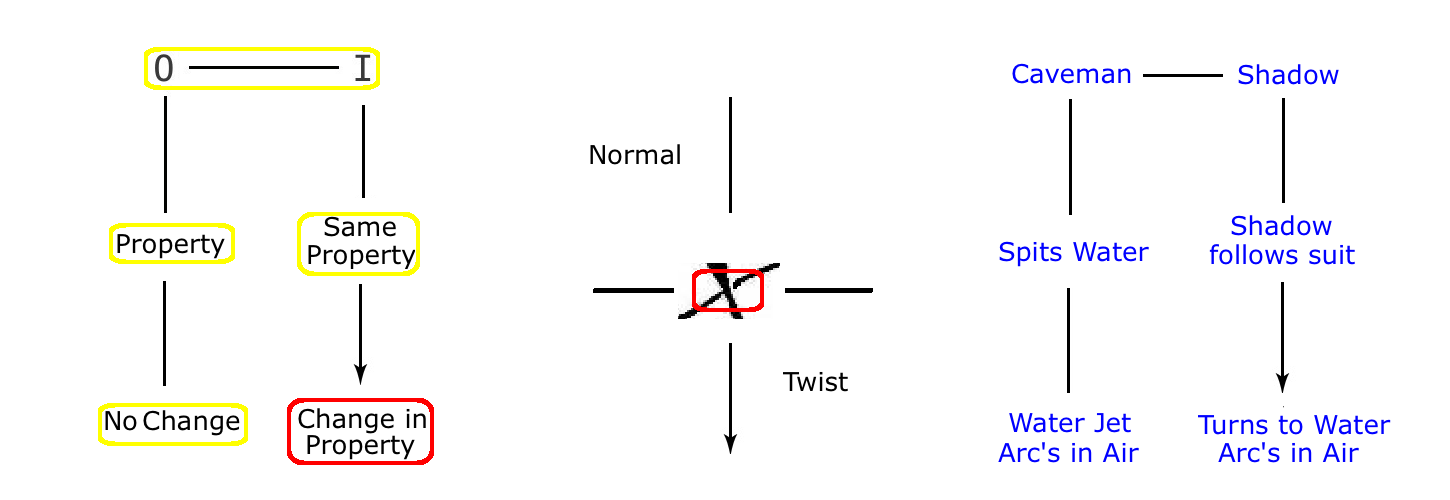

All of which leads us to a difficult question. Do we use the same diagram for both the ‘Shadow Spits Out Water’ cartoons, or should it be modified in the second example to take account of the differences between the two? Or is this problem due to a difference in visual presentation that the basic twist diagram is unable to take into account? Because if that is true, then this exposes a serious shortcoming of the model of the twist dynamics, given that the difference between the two cartoons is not only absolutely clear to us, but that it is also important in terms of the relative qualities revealed by the comparison.

The answer to this question is twofold. Firstly, the side of the joke that shows an image imitating a property of its original is covered by the two diagrams. But the diagram only covers the What, and not the How. So in the second cartoon, we see the sequence from normal visual correspondence to the twist, but without the actual visual presentation, where the join between these two stages is so well hidden, the how is left out of the picture (wrong phrase). Actually, this is why the diagram has included a thumbnail of the precise join as a reference, but this is hardly a systematic way of capturing this important aspect of the presentation. And the second reason for the inadequacy of the diagrams is much simpler. We have omitted a proper systematic reference to the state of play between the shadow and its master, which, especially in the second cartoon, shows a reversal of the power structure between the two. But as we are mainly interested in documenting the O/I twists at this point, that is a perfectly satisfactory position to maintain. For the moment. So, next question. How are these two cartoons being legitimised by the cartoonist?

To begin with, it should be clear that both cartoons rely heavily on the visual authority of the drawing to carry off their imitation twists (indeed, neither of these twists can be conveyed successfully in words). We see the shadows spit water out before our very eyes: a reality easy to accept when we consider that any image of a human being is an honorary human from the word ‘go’. So although shadows and reflections of inanimate objects are of some interest, some of the time, the images of animate beings, and most especially of humans, are of much greater interest to the cartoonist. After all, a shadow of a person can draw upon a wealth of meaning that the image of an inanimate object has no right to, giving it a privileged status amongst all the many other images in the valley of shadows and reflections. And because we are talking of imitation, where images follow their originals, it is just that the image follows a bit more faithfully than usual, making this a twist easy to swallow. Though in the second cartoon, the artifice of concealing the errant shadow in the symmetry of apparent visual correspondence gives even more credence to the final twist, because it really does look as if the image is behaving as it should (until we realise it certainly is not, but by then it’s too late).

Well, we can see from all of this that the original/image relationship has a built-in supply of legitimacy in the form of a natural visual pun, especially where animate forms are involved, and of course the principal animate form is almost always us. So any O/I twist where one side takes on more than its usual complement of properties from the other side is going to have an advantage because it carries what amounts to a built in legit. Namely, that the increased imitation involved in a twist always seems reasonable given that the shadow or reflection of a person looks very like a person in the first place.

Here is another example by the same cartoonist, using the same twist, but this time transferring a different property to the image.

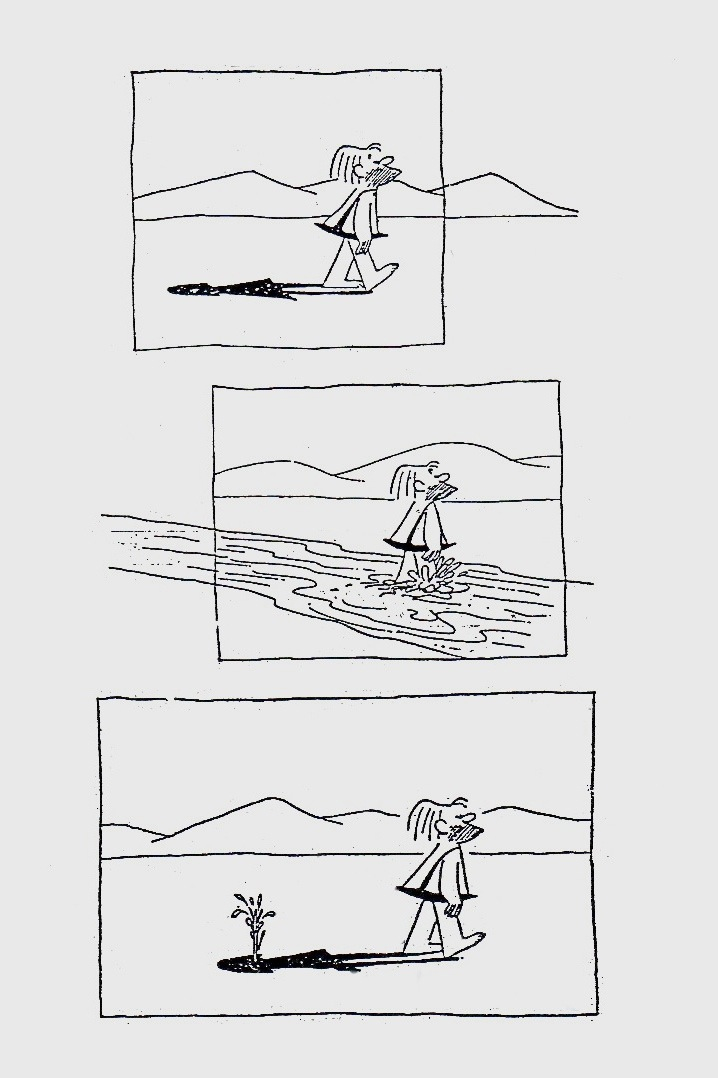

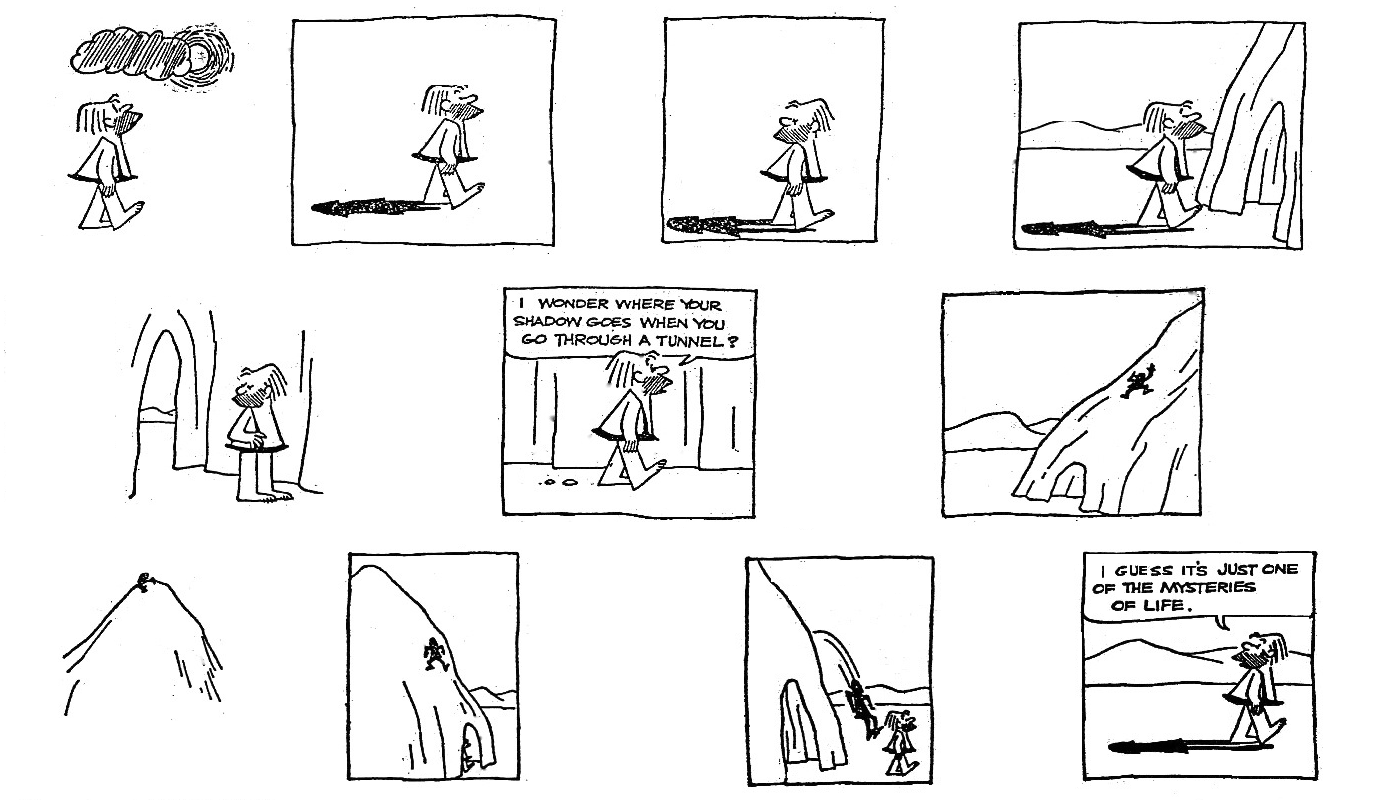

In frameless frame one, the sun is coming out from behind a cloud, and we are then shown the physical and cerebral passage of our caveman as he enters the tunnel, and wonders about the whereabouts of his shadow. Meanwhile we are privy to the larger picture, where we see the shadow climbing up over the rocks above, and then returning to his master. That is, the twist has completely torn up the visual correspondence between the original and his shadow, turning the shadow into a wholly independent entity in the process. (Not a bad feat, for what is essentially a patch of surface bereft of light). But then the shadow restores the status quo by returning to its rightful place at the feet of the caveman, on the ground. So the question is, are we looking at a simple ‘Image Changes/Original Stays the Same’ twist here, or is this something more complicated? Because it is one thing for the image to change whilst its original goes about its normal business, but surely another for it to move off on its own like this?

Could this be an image removal twist? Well, the shadow does climb away from his owner for a short period it is true, and this would constitute a removal if it wasn’t for the fact that it not only stays in the vicinity, but then rejoins its original at the earliest opportunity. And as we shall see further on, the image removal twist really does mean a total absence of an image (in conditions where there absolutely should be an image present). So this does exemplify the ‘Image Changes’ twist, but in extremis, because taking on a life of its own to the extent of temporarily rupturing the physical link between image and original is, at least in terms of visual correspondence, radical. An extreme move then countered by its returning to its owner as soon as possible, to restore the balance of nature, and give legitimacy to the caveman’s query on the whereabouts of his shadow.

To wit, what exactly is the role of the thought balloon in this third caveman cartoon? Well, without the thoughtful question about where do shadows go, the cartoon would definitely be poorer. Because the next four frames to follow this question supply us with the full and amusing answer to his query. So the question dramatises the situation by giving a point to the shadows alternative route: yes it is still there, but outside, following its master as best it can. On the other hand, without that question, the picture of the shadow climbing up the rock would have less meaning, because we would simply be looking at a physical twist, with very little reference to the world of humans. Then the shadow rejoins his master, without the latter seeing what has been going on, whereas we get the benefit of the aerial view, and see the whole picture. So while we, the audience, are treated to the ‘real’ answer to the question, the caveman is, quite appropriately, left in the dark. Again, this is clever dramatisation, because the caveman gives a quick look back, to check that his shadow has returned to him, and quietly accepts his ignorance by putting it down to ‘one of the mysteries of life’, without ever suspecting for a moment that the rest of us have been shown the graphic ‘answer’ to his question, and he has missed the whole thing.

Before we look more closely at the next cartoon below, note that these three preceding examples are all about a shadow behaving more or less independently of its master, relying in each case on the supportive logic that images imitate their originals, so why not take this a bit further, and make them into entities in their own right. However in the next example, we find a rather more powerful legit…

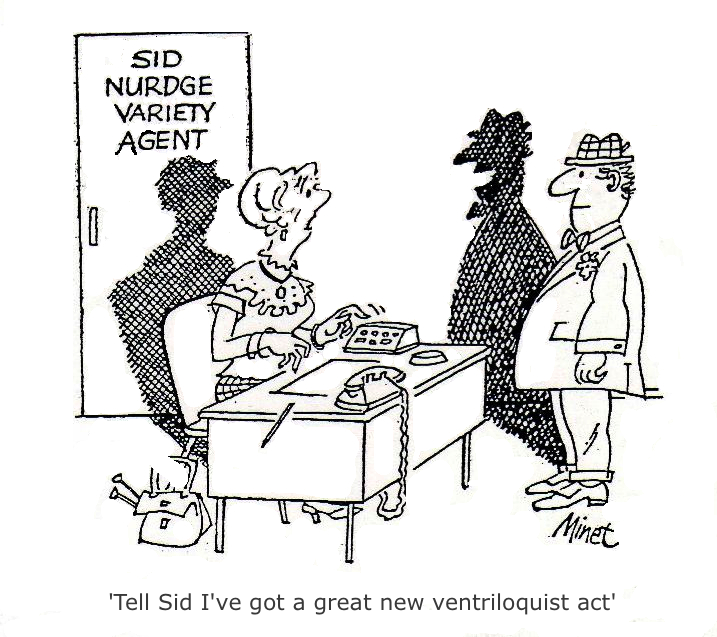

We should note, first of all, that there is a short delay in the ‘getting’ of this cartoon, perhaps because at first it looks as if the man is listening to something that the receptionist is saying. Hewison, a past cartoon editor of Punch magazine, makes an interesting comment on such delays:

‘I doubt whether any single-drawing cartoon needs more than five seconds to do its work – many do it in half that time – but even on the shortest fuse the cartoonist will make sure that we see it burning, then delay the impact until the last possible moment.’

We have seen this before. The puzzle set up by the cartoonist gains greater dramatic force if the audience has to put some effort into resolving it. And in this case, there is quite enough information (the caption, the title on the door, the two live characters and indeed the mostly normal looking shadow) for the small disparity in visual correspondence to remain unobserved for a second or two. Notice also that the legit is present (as is so often the case), in the caption, and that it is the caption that leads us into a resolution of the joke itself, with its reference to the very particular dynamics of this ‘great new act’.

So where does the twist in this cartoon find its immediate visual expression? Well, there is a disparity between the man’s shadow, the mouth of which is moving, and the face of its owner, whose mouth is not moving. Expressed in our terms, there is a breakdown in visual correspondence between the original and its image. A breakdown that is then ably explained and justified in the caption. Where we are told that the shadow is behaving like a ventriloquist’s dummy, which is to say that it is talking on its own, mouth moving, whilst its owner is saying nothing, mouth shut. Well, this is nothing less than a brilliant parallel between the shadow and its original, and the ventriolquist and his dummy. And it is one that fits not only because the shadow, like the dummy, is in close association with the ventriloquist, but also because they share the same generalised human form. We are left in no doubt therefore. This really would be ‘a great new ventriloquist act’.

In fact, we can look at the relationship between a ventriloquist and his dummy as similar in some ways to the relationship between an object and its image. To begin with, this is a case where both the original and its copy belong in the same context – and as we know, many copies do not follow that example. And then there is also some correspondence between the two, at least insofar as the dummy copies the human figure, and its ability to talk in real time. Indeed, it is precisely these two aspects that make it such a good source for a legit in this particular image twist. However, as most O/C pairs do not occupy the same contextual niche, their use as a source of legits for image twists must be limited, because the image twist demands that both elements have to be present in the same place. Nevertheless, the fact that we can now define not only the twist but also the legit in the terms of the two relationships covered thus far is a pleasing one. More importantly, it shows that once a number of relationships within the field of meaning have been properly identified, then the legits that employ them can be systematised too. Leading to the desirable situation where both the twist and the legit in a joke can be clearly understood in the context of that much greater roof above our heads that is the canopy of the human condition itself.

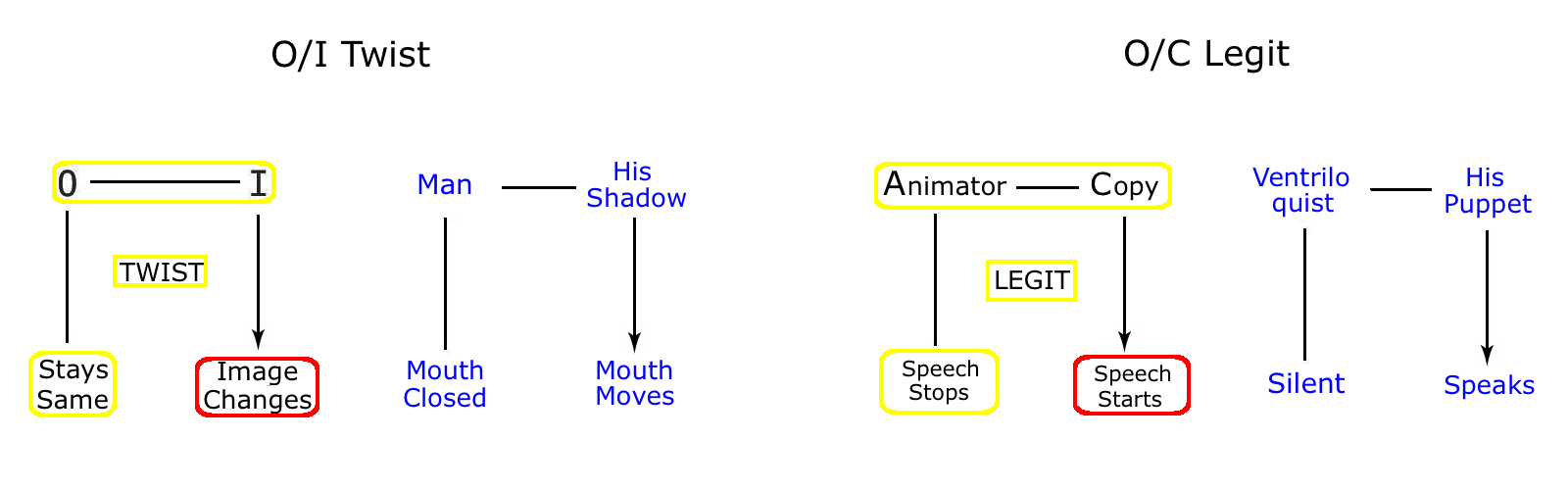

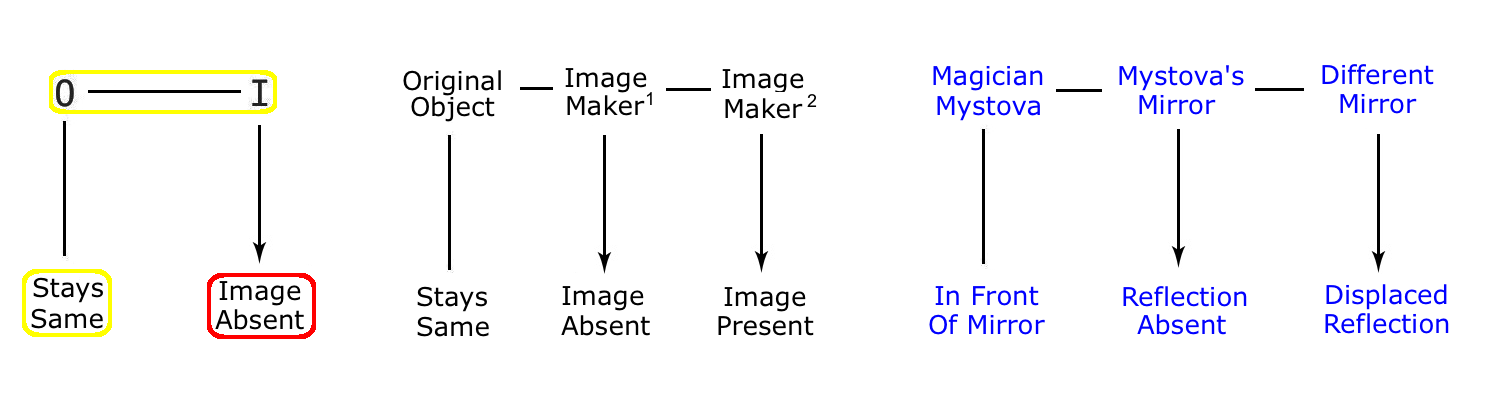

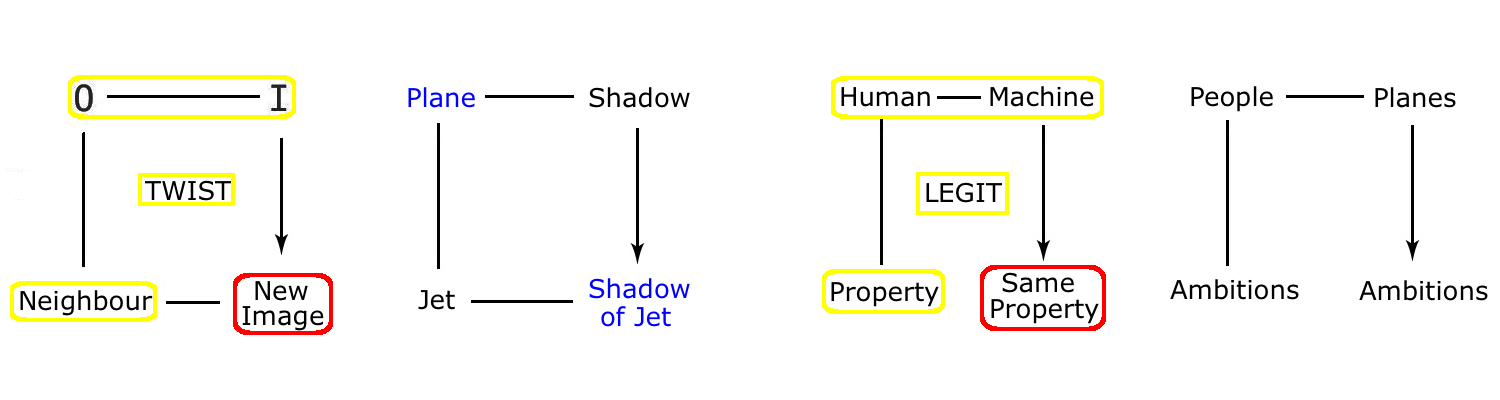

Anyway, here then are the simplified dynamics of the Ventriloquist cartoon, with the logic of the O/C legit provided alongside. Note incidentally that the O/C legit is based on copy animation.

This diagram makes clear the move from Image to changed Image, with the twist showing that the two elements are now paired off in this new combination, having left the old one behind, in the normal physical universe, where such novel pairings can never occur. The result is an O/I twist, and a O/C based legit:

1) The Twist: an image has taken on a property of its original – in this case, the shadow of a man has taken on the ability to speak (or more strictly speaking, the movements of the mouth that synchronise with his speech), and the result is a partial break in the visual correspondence between the two. Shadows do of course imitate their casting objects with slavelike devotion, so it is only one step further to imagine the image taking on a life of its own. Though a further justification is present in this case, so what about the extra and very clever legit in this cartoon?

2) The Legit: the cartoonist has set up a convincing parallel between the twist on visual correspondence on one side, and the role of a ventriloquist and dummy on the other. The idea that a ventriloquist’s dummy appears to talk whilst the ventriloquist himself keeps his mouth firmly shut is one we all recognise as valid. So when it is tied to the image twist, the result is a plausible proposition that seems to have its basis in the real world, even though we know perfectly well that the whole idea is at variance with the laws of the universe.

Notice, by the way, that there are only two shadows present in the drawing. The receptionist has been given her own shadow to maintain some semblance of reality, but that’s as far as it goes, because the desk and handbag are bereft of shadows for the sake of artistic clarity. A clarity that is nevertheless based on having that one other vital shadow of the receptionist present in order to show that things are generally normal – because without it, the shadow of the showman, all on its own, would look a little contrived.

This cartoon suggests further possibilities. For example, if the shadow is acting as a ventriloquist’s dummy, why not take this further, and turn it into that very thing? In fact, why not just go all the way, and draw a shadow of an actual dummy doing the talking? After all, why should the cartoonist stick with the shadow of the man, when he could use the shadow of a real ventriloquist dummy? Well, firstly there is a graphic problem – it’s not that easy to draw a shadow of a dummy that would not end up looking like a boy. Secondly, clarity would be lost unless we insert the real dummy on the arm of the ventriloquist, because without that reference, the shadow would be without a casting object (true, that is a different twist, but it’s not a twist needed here as the one we have stands best on its own). But put a real dummy on the man’s arm, and then drawing up a shadow that consists of the dummy and the man’s shadow makes it a little complicated too. Certainly, it would be possible to have the shadows jostling each other for room on the wall behind, but how much better to just show the man, and his shadow, without pushing the matter any further, because the caption makes it all clear anyway: this is ‘a great new ventriloquist act’, so we see the parallel between the image and the copy straight away.

There are a few more points to raise about this cartoon before we look at the next example.

1) The first point is that there is an additional and background legit in this cartoon, and it is a common favourite in cartoon humour: namely, the use of a ‘Variety Agent’. This is quite a common device in cartoons because the variety agent is a good way of reminding us how the entertainment world is always looking for something new. That in turn provides the humorist with a well-established and official means of proposing novelty, which is what twists are all about. Twists are indeed ‘great new acts’ that need a solid stage for their presentation, and the variety office fulfills that need by providing them with a rational basis for their existence.

This is similar to the smooth salesman in the ‘Something new in a wig, sir’ cartoon that we saw in the original copy section. In that case, the great effort made by the retail trade to constantly contrive greater novelty is well understood, and so, like the entertainment world, it provides a good stage for humour to propose new and outlandish forms under the guise of progress and creativity. So the reason why both the office of the variety agent and the retail outlet of the salesman are common in cartoons is not because they are funny per se, but because they make a good background legit for the twists in humour.

2) The second point that this cartoon raises is to do with the fact that casting a shadow that breaks the fundamental laws of the movement of light is one thing, but casting a voice that seems to come from another body is also pretty neat too. In fact, we can look at the whole phenomenon of ventriloquism as a twist in its own right. A twist that is a normally and naturally occurring one, albeit still a very impressive trick the first time round. And these naturally occurring twists are as common as the human need to seek and institutionalise our desire for fun. The hall of mirrors in the funfair is another example – curvy surfaces deliberately contrived to exploit the funny images that emerge from this particular and often unflattering form of visual correspondence. Nor do these naturally occurring twists need legits. Nor is this because they are too familiar to be a surprise, but simply because it is hard to argue with something that is happening before ones very eyes.

3) The third point that can be raised by this cartoon is the question: which contributes more to the joke, the twist or the legit? Because we could argue that the legit in this cartoon is rather better than the twist surely? After all, the twist is just a tweak in the visual correspondence between an original and its shadow, which is a fairly familiar theme in modern visual cultures like our own. On the other hand, the legit is a brilliantly contrived parallel between the twist and a naturally occurring twist from the O/C relationship. So surely the main value of the joke lies not so much in the fact that the mouth of the shadow is moving on its own, as in the caption explaining how this can be so? That is, the ‘what’ takes second place to the ‘why’, and it is the ‘why’ that elevates the ‘what’ to a stronger position in our judgement of the quality of the joke. All of which leads me to suggest that the legit is the best part, certainly, of this cartoon, and that it is often the quality of the legit that defines the quality of a joke in general.

If that is indeed the case, and the legit is as important, if not more so, than the twist, then this has critical implications. Because those attempts by other analysts to decode the joke that have managed to get a few steps into the idea of (what we here call) the twist as being a central element of the joke, and have then stopped there, are falling short of their objective to explain the joke. That is, they have not gone on to recognise this other critical element, the legit, as being an integral part of the whole joke dynamic, let alone recognise that the legit is just as vital as the twist.

4) And a final point before we move on to the next cartoon, and one I am keen to belabour. Thus far, we have been involved in mapping out the twists that attack a particular relationship. But eventually, when enough relationships have been mapped, it should be possible to show where the legits belong in the scheme of things as well. And this ventriloquist cartoon suggests just such a possibility. For it seems that we have managed to use it to define both twist and legit in terms of their membership of their particular relationships – the twist being O/I, and the legit being O/C. Now that is real progress, for it is the semantic landscape of the relationships that is our true aim. Map them, and the way they link to each other, and much more than the substance of humour is revealed. Rather, it is the very substance of the human condition that any real science of mind must aim for, and although that is still very very far from our sight, at least these cartoons give us occasional glimpses of what might be possible in the future.

In our next cartoon, we see the reverse of the twist above. So in this case, the ‘Original Changes, but the Image Stays the Same’.

2) The ‘Original Changes, but the Image Stays’ Twist

Here is a favourite cartoon of mine. It features a cartoon hero, particularly famous in Belgium and France, called ‘Lucky Luke’, who is not just any old cowboy, but a super cool dude.

Lucky Luke is billed on the back of every edition of his adventures as ‘L’homme qui tire plus vite que son ombre’ – ‘The man who draws faster than his shadow’. To wit, there is a bullet hole in the shadow silhouette, whilst the shadow has failed to reach his pistol, let alone shoot back. All of which goes to show that a gap in the visual correspondence between an original and its shadow may be only a second long, but that particular second is certainly enough to make a twist (and a death).

Now, how do we draw the dynamics of this cartoon? Well, using the format that emphasizes visual correspondence, we have this:

The legit for this breakdown in VC (visual correspondence) is based on the resemblance between the shadow, and a gunfighter who has been beaten to the draw, a familiar cliche in cowboy films. Which is to say that the legit has pulled our twist into a real life situation in order to make it realistic, at least for the moment of the joke, and that is all that counts as far as the cartoonist is concerned. Notice that the gunfighter in the legit is not only a category neighbour (because he is a fellow gunfighter), but in this case, seeing as this is actually a gunfight, a context neighbour as well.

It is important that the shadow is shown to be at least part way towards drawing his pistol – because if the cartoon shows the shadow just standing there, ready to draw, the joke seems somehow weaker. So why is this? Why is it better to show a measure of change, rather than none at all? Well, the answer seems to be that even a little change on the part of the image reminds us that shadows do follow their originals, and in addition, this also reminds us of the overall context of the shoot out where, at least in this particular case, the shadow is meant to be seen as the enemy.

Which brings us to a problem – because by moving a little, the image has strayed away from the pure form suggested in the twist definition, where the image is obstinate, which supposedly means it doesn’t move at all. So how do we reconcile this with our model? Well, the point is that the image is lagging behind its original, as opposed to being, so to speak, in front of it, which is what we see in the ventriloquist example. Which makes for a more complicated understanding of the twist, because it seems that both elements of the O/I relationship may be invited by the humorist to change. To wit, if the image leads, that’s one variant of the twist, and if the original leads, as in the cartoon with Lucky Luke, then that’s the other side of the same coin. All of which is not only consistent within the parameters set by the model, but is mentioned in the context of our introduction to the Obstinate/Fickly dualism above, where the idea that ‘the image falls behind or goes ahead of the casting object’ is also an acceptable formulation for breaks in VC.

The caption is interesting, because it could certainly stand on its own, without any drawing to help it. ‘Fast? Lucky Luke? He draws quicker than his shadow!’ But in this case the caption is there to support the picture, putting into words what we can already see in the drawing, and ensuring that there is no room for ambiguity. And together, the words and the picture create a dramatic and clear interpretation of both this twist, and its supporting legit. Maybe a picture is not always ‘worth a thousand words’ then, because in this example, the idea is carried perfectly well in nine words, though clearly the visual presentation is still infinitely preferable, just because it takes us so much nearer to reality that do the relatively abstract sounds and signs of language.

Finally, just a quick note on visual presentation. Notice how the depiction of the horizontal shadow lines of the legs connecting the two antagonists makes a nice visual link that brings the composition neatly together as one unit (as well as being strictly correct according to the laws of the universe, but we don’t need to worry about that). And perhaps without those lines, there could be some confusion as to the provenance and identity of the dark figure, though as we have just recognised, the caption is there to rid us of any real confusion.

3) The ‘Image is Removed, but the Original Stays’ Twist

There is a problem associated with the logic behind this particular twist. The question is, how do we know that an image is missing in the ‘Image is Removed’ twist? Because if it has been removed, then the fact that its original is standing there in front of us is no guarantee that there was ever a shadow or reflection standing there in the first place. Especially given that we know there is a paucity of shadows in cartoon drawing in general (if they serve no purpose, then they are just in the way, and are omitted because cartoons are all about economy of line and detail). So, how does the cartoonist show that the image was there in the first place, so that the absence can then be recognised as exactly that – a deliberate removal of the image?

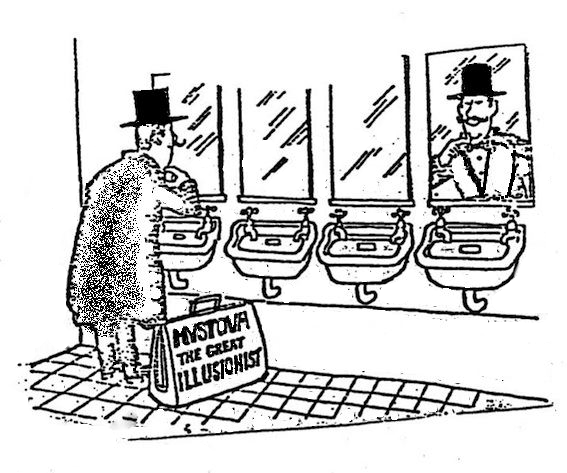

Well, one way is to use a two frame, before and after shot. A technique which can work either way, starting with an image and then removing it, or starting without one, and then bringing it back, perhaps as the result of an outside force (but not as a result of changing light source/surface conditions). Another way is to show several objects in the frame, all of which show a shadow or reflection, excepting for an obvious exception that stands alone, without a shadow or reflection, despite the conditions being right for its presence. Whilst yet another possibility is to remove the image, but put it nearby, so we recognise the break in visual correspondence as a displacement (not quite a removal, but it’s on the way). Which option is indeed the choice that we find in the ‘Mystova’ cartoon below:

No caption is present, but signs and labels often serve the same purpose, and that is what we find in this cartoon. The text offers us the legit for what would otherwise be an unsupported break in the visual correspondence between an object and its reflection. And the legit comes from the world of entertainment – again. It seems the break is the result of a clever conjuring trick. Well, by now, we are beginning to see that this world of entertainment is a serious source of legits for humour. We have already seen this with the Ventriloquist Act, and now it is the Conjuring Act (and later on, there is a Hall of Mirrors legit). And as we have touched upon before, the entertainment industry is like the retail industry – it thrives on novelty and unusual results – and once we start expecting things to be unusual, it is easy to carry that further, and take the next step that turns reality into a real twist.

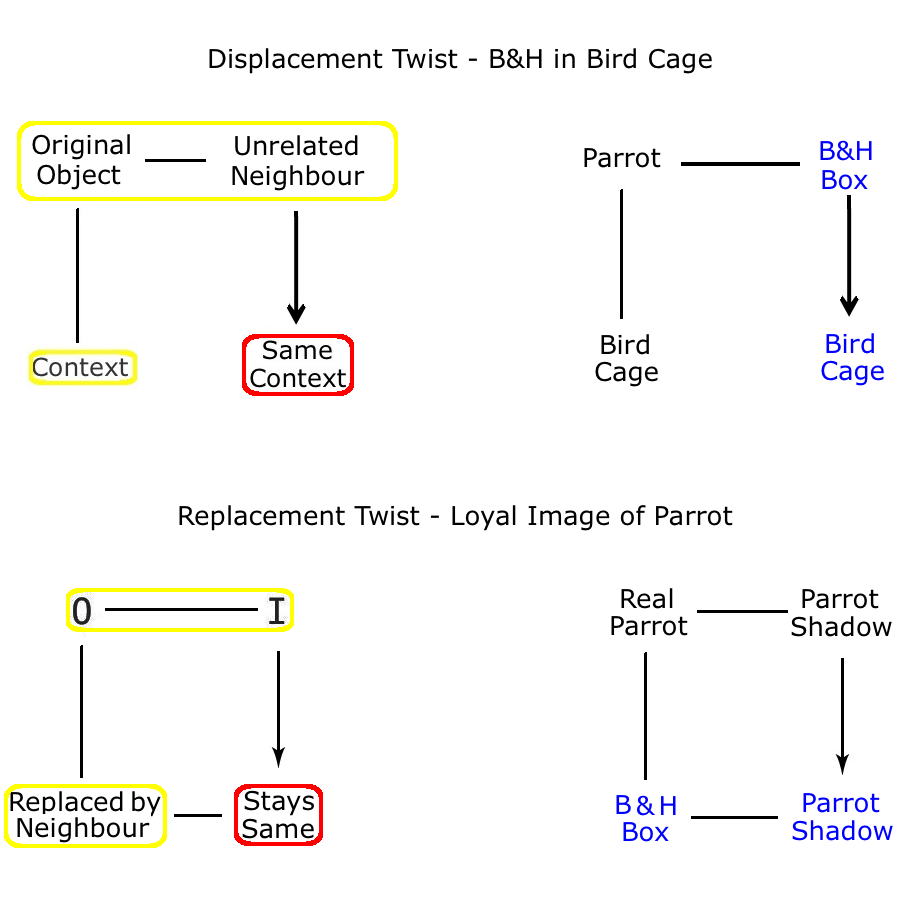

Here then is the diagram summarising the elements of this cartoon. The image is removed from the mirror, but emerges in another, so we are looking at a displacement here, but that’s all part of the continuum between change and removal (it is both an absence, and a move, but this does not add up to a total removal from the picture).

This cartoon is weaker than either of the previous ones, probably because its legit is not as compelling and as original as the ventriloquist or gunfighter legits. Now, the easiest way to find out whether this is true would be to ask a good sample of informants. But if our guess is confirmed, then how do we even begin to think about quantifying and explaining this difference in quality? In particular, how do we analyse the relative quality of the two legits in say the Mystova and the Ventriloquist cartoons? Well, one basis for examining the two may rest on the relative semantic distance between the twist, and the legit that supports it. For example, this comparison shows that in the ventriloquist cartoon, the copy legit fits the image twist like a glove, whereas in the Mystova cartoon, the legit is so inclusive and general that it embraces all manner of twists. Yes, it fits, but its fit is comparable to how the mouth of a dumpster fits a tin can. And if we compare the Mystova legit with that of the gunfighter parallel in the Lucky Luke cartoon, then we find that the gunfight parallel again fits like a glove, in sharp contrast to the ‘explain any anomaly away’ of the conjuring trick. So the relative ‘degree of fit’ between a context and the number of candidate twists that it can apply to seems to be an important issue here. In which case we would expect to find that the conjuror legit fits far more twist examples than either the gunfighter or the ventriloquist legits, and is therefore more common and less effective as a result. Well, this is an important question that can be pursued when more cartoons have been analysed, so for the moment, we must leave this issue at the level of ‘Fits like a Glove versus Fits like a Dumpster’.

In examples where there is a complete and manipulated absence of the image, and not just a displacement like the one above, it is still possible to achieve this in a one frame cartoon, just by ensuring that all the other casting objects are showing a reflection or a shadow. For example, we can imagine a pair of sentry soldiers outside Buckingham Palace in London, complete with their huge bearskin hats, where one has a shadow cast out over the pavement, and the other does not. But then we have the problem of how to justify this anomaly…and that is often rather a challenge. So we can imagine a different scene where a group of schoolboys stand in line before a teacher who is admonishing them, demanding to know which of them has been playing truant. The guilty one is depicted without a shadow, whereas all the rest have a perfectly neat line of good shadows, and for good measure, the heads of these shadows can all be looking towards the boy without one. Whilst the boy himself stands there with his face looking up, and beaming with total and disarming insouciance

Here is an example drawn from the advertising world, showing a complete removal of the image (unlike the displacement of the reflection in the Mystova cartoon).

Here there is no question about it: the shadow is absent. Now whether this means the image has been displaced elsewhere, or has just disappeared altogether is not of interest as far as the viewer is concerned, but the absence needs to be explained. So are we supposed to read into this picture that the sunblock they want to sell to us is so good, it even blocks the sunbathers shadow? A notion (of a lotion) that doesn’t bear much scrutiny if we think about it more carefully, but in any case this is a poor presentation because the absence is not dramatised (we have to look for it), and then no effort is made to back it up with a legit through a caption or other means. We are forced to look for a reason, if we are bothered to do so, and my guess is we are not, because there is too little attempt to pull us into this putative puzzle.

The sun lounger has to be there in the picture of course. Not because it backs up the idea of sunbathing (though it does do that, which is why it is a lounger and not a flowerpot), but simply because an object that does throw a reasonable shadow has to be there to show us that the absent shadow elsewhere is an anomaly. It being the case that if the lounger was absent, we would almost certainly ignore the absence of shadows in the picture anyway. Or if we did notice this absence, we could surmise that the shadow is not visible due to the angle of our view, or the angle of the sun. Or that the artist/photographer has simply not bothered to factor in a shadow, or has even deliberately left it out for artistic purposes.

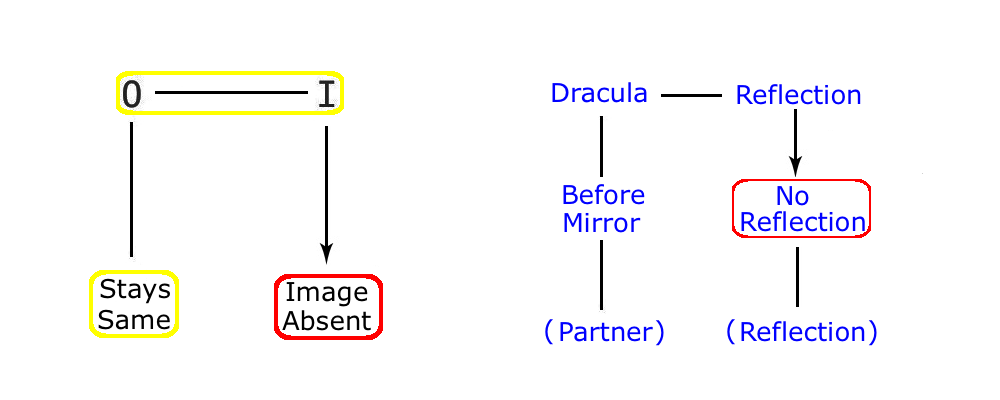

In the next two examples, we are reminded that certain figures, and in this case Dracula, do not cast a reflection in a mirror because of their metaphysical nature. There are rather too many cartoonists that have arrived at this same idea: namely, that this would pose a problem for Dracula when he needs to brush his hair or shave his chin.

The legit is carried in the speech balloon, and is based on the accepted naturally occurring twist that Dracula has no image, so when he looks in a mirror, he has no reflection. Speech balloons are just another way of creating a caption, though the caption has the dual option of either standing as a comment from the cartoonist or standing as a comment from the figures in the picture. In addition, cartoonists probably prefer the caption as it takes the verbal clutter away from the picture, and therefore gives proper artistic integrity to the visual presentation of the cartoon.

What is interesting about this example is that it features a well known, and in the context of humour, a naturally occurring twist about Dracula that is not intended to be at all amusing. In fact, if anything, the idea of a figure looking into a mirror with no facing reflection is intended to inspire awe, fear or a feeling of deep mystery, and certainly not humour. Yet it clearly involves a twist between Original and Image, just as in this cartoon. A twist on visual correspondence, where the image is absent, and the legit is about special powers and the metaphysical world. The difference being that such claims to denials of the laws of physics are meant to be taken seriously, rather than laughed at, in the world of superstition and metaphysical belief. Yet clearly these claims are just as ludicrous as those of humour. (In fact, more so, given the extreme credulity required to believe them, and perhaps even more so, given that humour does not take itself seriously at all). All of which suggests that the twist and indeed its backer, the legit, are likely to be found elsewhere and outside of humour. Which is obviously the case, because one only has to look at the claims of religious belief, or the worlds created in the name of fiction, and the ubiquity of ideas that transgress both physical and social norms becomes very clear. For example, in the Harry Potter world, we see examples of both types of twists intertwined as a fictional account about magic that features both attacks on the physical and the social world with, in an important sense, none of it being true at all. But at least, like the humorist, the novelist is not, even for a moment, taken in by such fabrications. The same cannot be said for those amongst us who have ‘faith’, and therefore swallow all kinds of fabrications as if they were actually true. But the study of these fabrications, which we have been referring to as twists, is nevertheless every bit as feasible as it is for humour and fiction, and is an important part of our advance towards a science of meaning.

4) The ‘Original is Removed, but the Image Stays’ Twist

As we have already noted, there are logistic problems associated with taking away a member of the O/I relationship, especially with respect to the image, simply because, for a variety of reasons, there may not be an image present in the first place. The question is, might there be a logistic problem the other way around as well? That is, could there be a problem of presentation when the image stays, but the original is removed?

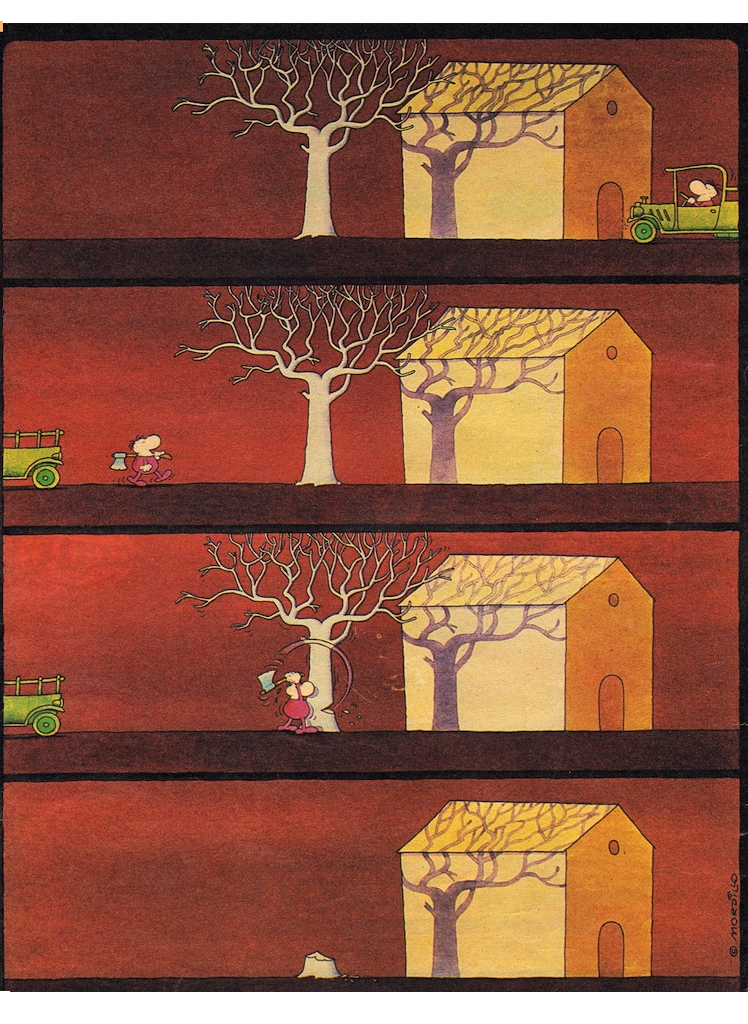

In fact, in the physically limited field of view defined by the frame of a cartoon, it is possible to have an image that seems on its own just because its original casting object is standing outside this field of view, so conceivably that might confuse the issue a little. But generally, if a shadow or a reflection is present in a scene, and the casting object is not, then we are likely to recognise this as a twist very quickly, because images are entirely dependent on their originals. That said, it is often better to use at least two frames to present this particular twist, as that gives us a ‘before and after’ that leaves no room for confusion. And that way, we start by presenting a normal pairing of the original and its image, and then the original can be removed in the next frame, with the image staying where it is, to make the twist. As in this multi-framer by Mordillo:

There is no legit in this cartoon – just the visual authority of the picture itself. This is perfectly normal in the case of this cartoonist, who often keeps to the visual, and avoids the verbal side, with the obvious advantage that his cartoons are therefore entirely international. The disadvantage is that the caption is the ideal place for the legit, and without any kind of legit, the joke is less compelling.

Why is it that the caption is an ideal place for the legit? Surely a legit can just as easily be presented visually as it can verbally? After all, if the picture works for the twist, then it must work for the legit too one might think. Well, perhaps. But the problem seems to be that the primary act of the joke is to set out a twist, and in a cartoon this tends to be presented visually, which then leaves, as it were, less room for the legit to be carried in the same semantic space. In addition, pictures do not have the capacity to carry meaning as language because they only deal with the visual dimension. Word pictures are much less effective than real ones in some ways it is true, yet much of our meaning is above and beyond our visual sense, and much of our insight is based on abstractions and events that are often impossible to capture with a line or a colour. For example, there is no way that this paragraph could be put easily in a visual form. So the verbal caption gives the cartoonist the power to add other situations, and reference points to the twist in the picture, making the caption an ideal location for the legit.

5) The ‘Image is Replaced, but the Original Stays’ Twist

Replacement twists are comparable to the sidestep twists in the O/C relationship. Comparable because they also involve a sidestep to a neighbour of either one of the two elements of a relationship. But although a casting object from the O/I context has many neighbours, it is not entirely clear whether the shadows and reflections cast by its presence have neighbours as well. The point being that such neighbourly images are nothing more than the reflections and shadows of the neighbours of the original and its neighbours. So images do not have their own set of neighbours, but merely the shadows and reflections around them, and these belong to their originals, not to them. Anyhow, this next cartoon is clear enough because it is an example where the casting object most certainly does have a wide range of neighbours, and one of these is a supersonic jet.

Small planes have all sorts of neighbours: for example, a glider is a property neighbour, and a nearby helicopter or jet parked at the airport is a contextual neighbour, whilst other planes of the same type are category neighbours, and the plane also has copy neighbours, such as a toy plane, and image neighbours, such as we would normally see in the photo above if it were not for the twist. Now in this case, the neighbour is a military jet, and that is a choice that makes sense to humans, because we can imagine the plane as animate, and therefore open to animate desires, such as wanting to be bigger and faster. In other words, we have now discovered a picture where both the twist and the legit are carried by the same medium, with no words involved. Because the break in visual correspondence is a clear picture, writ as it were on the sand before us. And the legit, with its very human side of always wanting to be better is surely, whilst not writ on the sand, nevertheless pretty clear to most of us as well. Indeed, to the extent that it is not, then the cartoon is a puzzle, and so much the better.

A caption would help in one way of course. So a brief title like ‘Every plane’s secret aspiration’ would pull in the stragglers who had failed to see the sense of the twist. But it would also damage the succinct nature of the cartoon, spelling it out when it is much better to leave it as a problem that has a quick resolution, whilst giving us a brief moment of pleasure in its speedy solution at the same time.

Anyway, here is the schematic for this particular example of the image replacement twist, with the legit alongside. Notice that although the legit is presented in twist form, its familiarity as a way of thinking is so great that it has to be defined as a naturally occurring twist. So what makes it a twist at all in that case, because if it occurs naturally, then surely it is not a twist? Well, machines do not (as yet) think like humans, so this simple little plane is certainly not an entity capable of ambitions of any kind, which means that this must be a twist. A twist that is so commonplace, given our normal reaction to animals and even machines, that it hardly seems like a twist at all. But it makes a great legit in this cartoon, and the fact that it is implicit to the picture, with no caption spelling it out, enhances its otherwise reduced value as a cliche.

One can easily imagine other examples of this simple but effective twist idea, although it should be noted that it is the legit that forms the real basis of this joke, as breaks in VC are a relatively simple idea. So, why not use a copy neighbour, because it is easy to imagine a toy wanting to be the real thing, and casting the corresponding shadow as a result (though showing that the shadow represents the real thing could pose problems if they look the same). But that problem could be solved by choosing a Toy/Original pairing where there is a distinctive difference in silhouette between the two, and as some toys have a rounded simplicity about them that is in stark contrast to the shape of their originals, they would make the best choice. For example, a toy soldier could aspire to be a real soldier (or maybe a toy soldier of higher rank, all within the copy side of things). But either option looks hard to represent in practice, so what we need is a figure that is not only lowly, compared to another in the same context or set, but also visibly distinctive from the figure it aspires to be (so let’s use a reflection if we are short of the necessary detail). Et voila:

So here we see just four of the numerous examples of this idea in the google image photo library… because this idea is clearly a winner. Why so? Because conscious beings really do stare at themselves in mirrors. Because little beings really do want to be big beings. And because pawns really do have a legitimate expectation to become the queen, according to the rules of chess. There are also examples using shadows, rather than reflections incidentally, and they work quite well too.

This photomontage is an example of a practical problem that often comes up with reflections. The question is, how do we fit an image-making mirror (or stretch of water) into the context of our planned twist – when one may not belong there? For example, a shaving mirror has no serious claim to being in the same room as the members of a chess set. However, by keeping the picture simple, and with only the essential protagonists being present, this problem is successfully sidestepped, and the result remains uncompromised by such contextual rigours. Meanwhile, the pawn dreams of becoming a queen, whilst its size and roundness remind us of its lowly, almost baby-like status, thus dramatising the difference rather nicely.

One reason the pawn looks cute is that there is another, albeit thoroughly familiar, twist at work here. It is the same as the one we have just encountered in the ‘Plane as Jet’ cartoon. It is the result of the anthropomorphic app that we all have in our heads that readily converts not only animate, but also inanimate things, into honorary human beings that have thoughts and feelings of their own. And both the little plane in the previous case, and the pawn in this cartoon, have taken on that status by virtue of the image replacement twist. So in each case, the creator of the joke exploits our readiness to think anthropomorphically, in order to justify the break between the object and its image. ‘Poor little pawn, of course it wants to be queen!’ Meaning that the break in physics is entirely justified by the greater meaning that we see in the human situation, this being the context we most easily relate to. And the moral of this? That although Social Space is based on, and has emerged out of Physical Space, it is the former that takes precedence in our minds, even at the cost of denying the reality of the latter. And the moral of that? Well, we don’t deny physical reality when it really matters, but we do get our cake and eat it when it comes to virtual events inside our head, because there, we are free to indulge our imaginations more or less wherever they lead

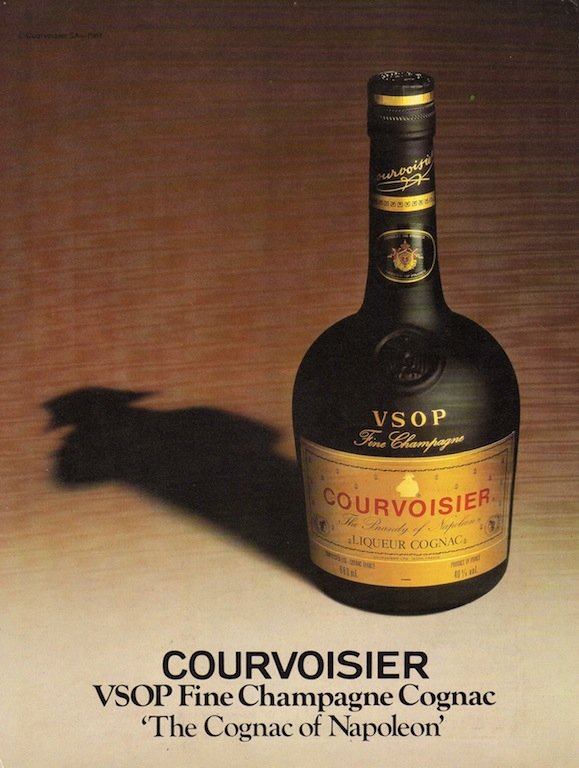

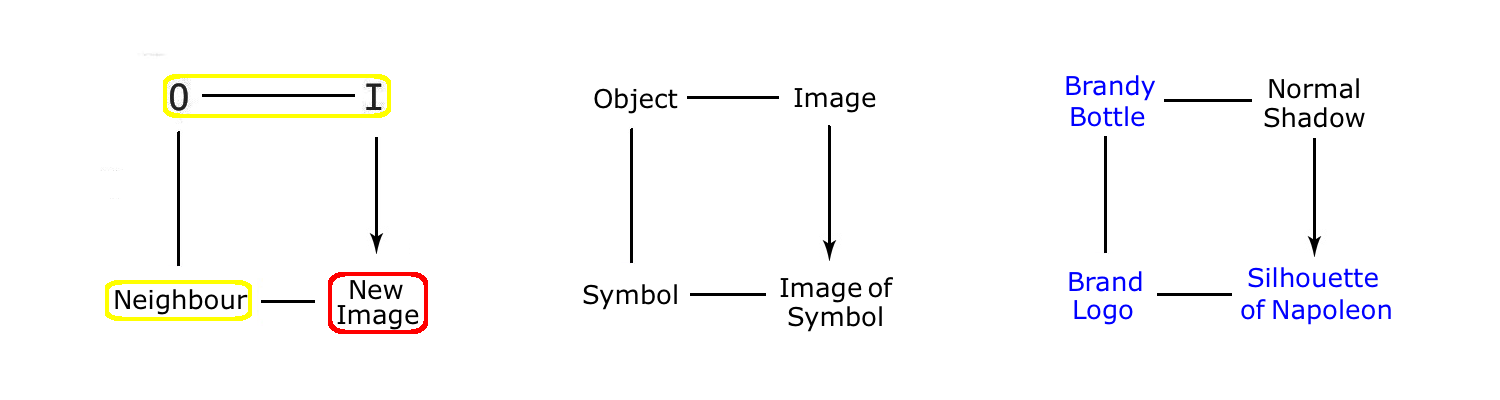

It seems then that the image replacement twist thrives on is pairings from Social Space. And the world of advertising has not been slow to appreciate the possibilities here. So in the following example, the shadow reveals the symbol of the brandy, which is the figure of Napoleon – and the ‘caption’ or in this case, selling line, ensures that we are in no doubts as to who and therefore what, the shadow represents.

One aspect of the legit is simply the authority of the photomontage, which is more compelling than a cartoon because, even nowadays, we are used to taking photos seriously. Another aspect of the legit is the simple logic of the sidestep replacement twist. There are two ways of looking at the dynamics of the sidestep: we can picture the path of creation, which is what we effectively see in this diagram above, or the path of resolution. My guess is that the path of resolution runs like this: We see the bottle, and spot the twist in the shadow, at which point we cast around for an explanation, and see the link between the shape of the shadow and the symbol of the brand, and all becomes clear. The connection and the logic are established, and the break in VC gives way to a higher human logic, where brand pairings between product and symbol lord it over the laws of light. Now let’s look at another example which seems to go a step further:

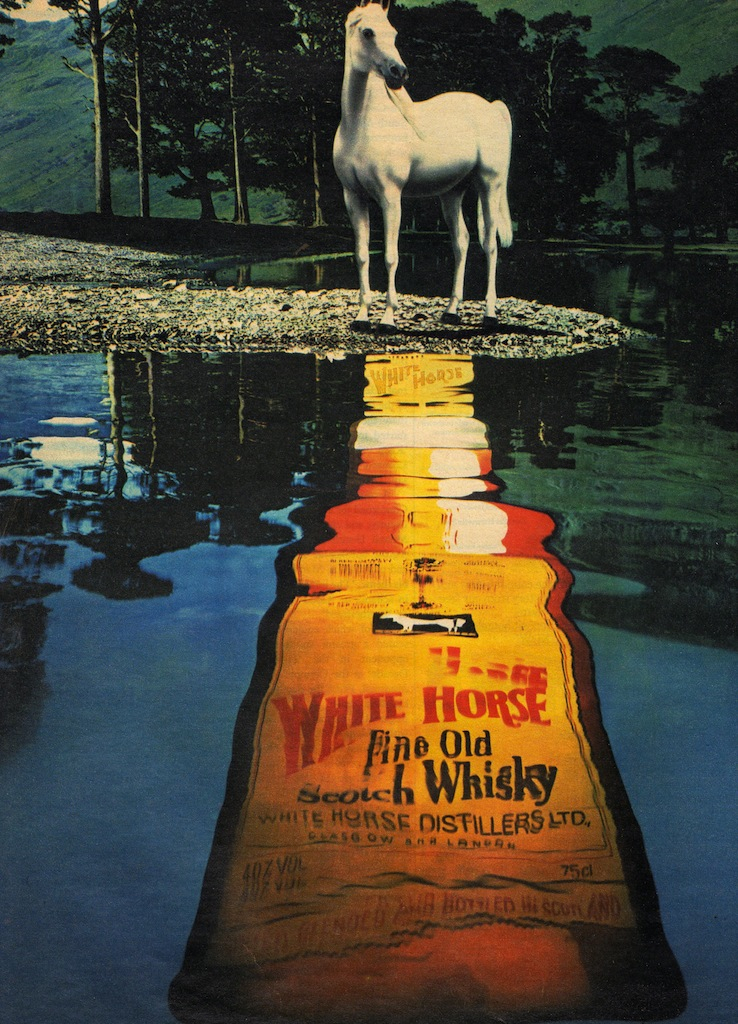

Notice that the advertiser had to use a reflection in this picture – to use a shadow of the bottle would result in an unrecognisable shape, both in terms of brand recognition and twist resolution. Note also that the top and bottom of the bottle have been reversed – really the foot of the bottle should reach out from the bank, where the feet of the horse symbol are planted. Again, marketing expediency is the driving force. The label has to be read with as little effort as possible, and that makes this additional breach of visual correspondence entirely understandable, given its commercial context.

Now, in this case, the white horse standing on the bank is not just the original of a normal reflection of a horse (absent to leave space for the brand reference in this case). Because it is also the symbol of the White Horse Whisky brand. Which means that the bottle of whisky is actually the original to this horse symbol, in the sense that the thing referred to by the white horse is the bottle of whisky. So we are looking at two relationships here; the one between an Original and its Image, and the other between the Original and its Symbol. There are thus two original objects in the twist dynamics in this example: namely the horse and the bottle. And given this set up, it is also possible to put the originals the other way around, and arrange to have the bottle on terra firma, whilst the white horse is shown as a reflection in the lake, just as we find in the previous example of the Napoleon brandy. But would that look as good? A bottle of whisky standing proudly on the bank, with a white horse as its reflection? It would not. Much better put the horse on the bank of this beautiful natural setting in Scotland, where it clearly belongs, and allow the bottle to ripple out in front of us, in a sufficiently large and magical display of the primary product, and for all to see. Which is why the creators of this ad chose to put the symbol on the bank, and the image of the bottle as a reflection. So what if they had chosen a shadow instead, and tried to do the same as in the Napoleon brandy twist? Well, they would have been in trouble with the shadow of the horse, which would not have extended neatly away from the bottle in the same way that the silhouette of Napoleon does. The problem being that the four legs are spread out, making it near impossible to create a good visual correspondence between the bottle and the horse, so the neat result we see in the other example would not have been possible in this case.

The whisky bottle ad has moved us over a step from where we were with the cognac bottle. We have gone from the ‘I of the S of the O’ to the ‘I of the O of the S’ (from the Shadow – Napoleon – Bottle to the Reflection – Bottle – Horse). A step that seems to make things more complicated. But is it more complicated in reality? Perhaps the best way to answer this is to observe that visual symbols like the white horse exist primarily in Social Space whereas the original casting object exists primarily in Physical Space (it is a bottle, not an icon). Well, given the manifestly physical situation that image twists always find themselves in (which is why they are normally found in cartoons rather than in verbal jokes), it just seems to add a further step to take the original away from the driving seat, push it sideways into the passenger seat, and give its symbol the primary position. Unless of course this is all just an artefact of the direction of our analysis, where it seems like a further step from whence we have come, and where in fact both are equally complex, or indeed equally simple. For example, it may depend on where have come from in the first place. So, if we had been examining things from the symbol rather than the image point of view, it would be the whisky ad that seems simpler than the cognac ad. Interesting certainly, though the White Horse ad still seems a bit more far fetched for some reason. Maybe it’s just down to the visual correspondence lack of fit between the white horse and the reflection of the bottle? Because some greater similarity in the two shapes would surely yield a better result.

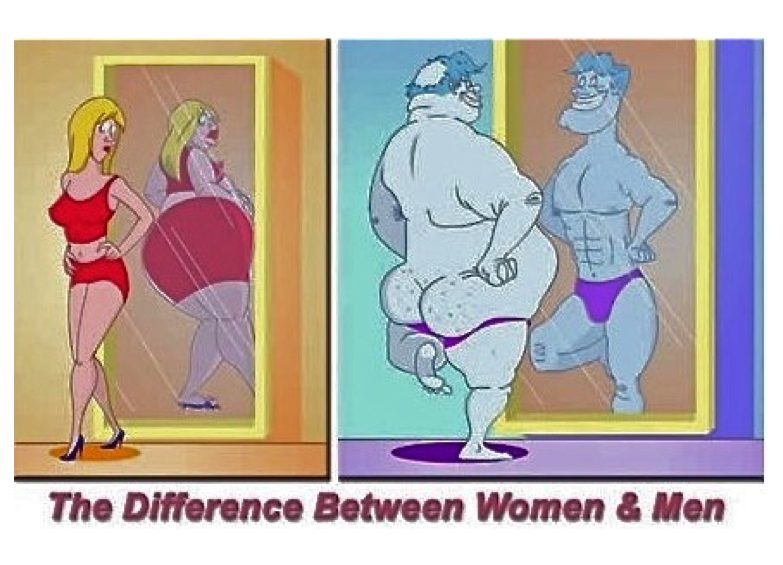

Here is another cartoon, and one that presents us with a bit of a puzzle. Because at first sight, it seems to be replacing normal images with new ones. New images that represent the worst fears of the woman and the best hopes of the man. But are these replacements of their originals, or are they just modified images of their owners that have been changed to reflect their individual fears and hopes? Are we looking at a pair of replacement twists, or at a pair of ‘Image changes, but Original stays the same’ twists?

To resolve this, it helps if we imagine an example where the images are clearly replacements. So, if we make the man younger, but at the same time increase his age markedly in the mirror, the result is a young man in his prime looking at a bearded and stooped image of himself. Now, is this therefore an example of an image change or an image replacement twist? Well, if we argue that it is still the same man in the mirror, just somewhat aged, then it is a change twist. And if we argue that the old man is so displaced from the real young man (in terms of time), that we are effectively looking at a category neighbour, rather than just a simple change in the image, then it is an image replacement twist. At which point it looks as if this is getting rather academic and pernickety.

The reason this problem of definition arises at all is due to the continuity between change, removal and replacement. This is partly because these terms are part of our normal language, and can be stretched around somewhat. For example ‘change’ can mean almost anything, and include removal and replacement in normal parlance. However, that is not the case here, as we are trying to discern some real differences in this range of joke logic. So, to begin with, the term ‘change’ excludes removal and replacement, and in the process, concerns itself exclusively with the properties of its owner object. At the same time, it is clear that ‘displacement and removal’ are about the position in space of the image, and that ‘replacement’ is about the use of a neighbour (a membership that works through having a similar property, home space, or belonging to the same category). This gives us relatively clear boundaries between the three states. Nevertheless, grey areas are bound to emerge repeatedly in the world of meaning, where even the simplest symbol is nested in astonishing complexity once its connections are revealed. Because what starts off as a quantitative shift in an object (as in our example here, where the human figure ages), can turn into a qualitative jump (from a ‘young buck’ to an old man), and this is perhaps where the trouble lies. Simply because it then changes our identification of the twist. But iin reality, this hardly matters, because all it does is nudge the twist identity along a bit within the overall continuum of change through to replacement.

Which means that, for example, the shadow of a small oak sapling, stretched out over the ground from an acorn, is a replacement twist. Whilst if we have a rose in bloom, with a reflection in the garden pond of a plant where the flower has already gone to seed, with the petals crumpled up and falling out, then we have a problem, because this is where the boundary turns out to be a band, rather than a clear line in the sand. A problem because of the temporal proximity between the fresh and fading flowers, making us wonder whether they amount to what is effectively the same flower, or in fact that they are qualitatively distinct phases, not to be confused with each other.

For the moment then, the cartoon of the two figures can be defined as an ‘Image Replacement’ twist because it is one thing to copy a property, and another thing entirely to replace the whole body with a different one. This is because the images of the fat woman and the muscular man are both reflections that represent the pessimistic or optimistic readings of their originals, and these readings are quite separate from the reality of the two people we see before us. They are therefore a pair of category neighbours that are replacing the two true images in the mirror.

Here then is the schematic for the pair of replacement twists of the man and woman as they appear in the mirror. This represents a double denouement in that it benefits from two dimensions of meaning: we see both sides of the question, not only from the gender point of view, but from the visual correspondence point of view as well, because the latter carries two possible outcomes as well (fat to thin, and thin to fat).

We can imagine that this cartoon would also work if the two sexes had been portrayed the other way round, switching the hopes and fears so that the man now sees his worst fears in the mirror, and the woman, her highest hopes. Either way, the picture is not just amusing, but insightful in the way it portrays our concern with our physical appearance, and the gap between the reality of the mirror image, and our hopes or fears.

Now we can move on to our sixth and final type of twist on visual correspondence, and this time it is the original that gets replaced, whilst the image stays the same as it was before.

6) The ‘Original is Replaced, but the Image Stays’ Twist

In the next example, also taken from the advertising world, we find the famous and iconic brand of cigarette box used by Benson and Hedges – sitting in a parrot cage. Not funny perhaps, but certainly at least a bit of fun and somewhat droll also. Which is what this whole B&H advertising campaign was all about. Because around about that time, the marketing philosophy behind advertising had changed to the so-called ‘Tickle them, not tackle them’ phase. So all the ads from this campaign featured the displacement of the famous ‘Pure Gold’ box from its normal habitat of smokers pocket or supermarket shelf to the weirdest places, and in the strangest forms possible. For example here, we find a displacement twist of the sort we featured in the ’Slipper in the Oven’ cartoon, where an object from its normal habitat is put into a place it would never normally belong. But it is not the displacement that gives the real force to this picture before us. Rather, it is the additional twist, this time on visual correspondence, that gives the real value to this scene. Because the shadow on the wall should be the shadow of that nice gold cigarette box inside its cage, but in fact it is not. Instead we find a profound break in the visual correspondence between the original and its image at this point. Not only is the shadow not true to its original, but there is an imposter shadow in its place. An imposter that is actually the rightful inhabitant of the cage as far as human logic is concerned. Because the logic of what should be an entirely physical circumstance has been replaced (literally in this case), by the logic of where human objects belong in the human scheme of things. So the break in physical logic has, so to speak, been filled and healed with the glue of human meaning, to create a bond we all find acceptable and pleasing.